On a fine, particularly lethargic morning as I was aimlessly doom-scrolling on Instagram, I stumbled upon a post by a very new Indian “premium” fashion brand that uses indigenous crafts. The short video opens with a sepia-toned picture of an open area with old buildings washed in a muddy yellow colour, with steep staircases lacking railing or any support. On the ground level, in focus are the numerous equidistant rows of big vats filled with dyes, while a few scattered people are bent over them, dyeing. A text appears on the screen: “Reviving age-old traditions in the purest form of Indian craft.” Just as I grasp the words, the scene cuts to a colorful block-printed cotton fabric put to dry in the open breeze. As it playfully sways and adjusts itself to the focus of the camera, a short informative text follows, identifying the natural dyes of India and their origins. But I saw a picture of that place before; it wasn’t India, it was a leather tannery in Fez, Morocco!

“This dominant visual culture [of the ‘exotic’ village] has now grown to merge geographical identities to create new ones enabling fashion brands to indulge in using visuals that more or less create a vibe of the Indian village.”

It could be dismissed as an erroneous public post by an ill-informed individual who was responsible for the brand’s social media, but nonetheless, such mistakes need to be analyzed in the interest of a larger perception of an unmistakable visual imagery of India. An increasing interest in crafts can be seen today as domestic fashion brands, with varying levels of sustainability, portray handcrafted clothing through an endless romanticization of the Indian village. Aiming at the domestic consumer with a global outlook, a common denominator in such pictures of the rural landscape is the overarching objective of reviving the traditions of India. With Google showing you “visually similar images” and Pinterest asking you if you want to see “more pictures like this,” this dominant visual culture has now grown to merge geographical identities to create new ones, enabling fashion brands to indulge in using visuals that more or less create a vibe of the Indian village.

Indeed, I would not have recognized the original location in the picture, if not for a YouTube video of the tanning process in this town that I had watched a few months earlier. For a second, I was almost convinced that it is an Indian village—the landscape, the dyes, the vibe… the sepia tone itself! Artist and researcher Luiza Prado de O. Martins writes an intriguing account on the role of the yellow tint in cinematography used to represent locations in the Global South. Since the process of conceptualizing fashion often starts with a mood-board, such images that help to bring out the mood of the “exotic” origin of the product and its exquisite quality of being delivered to the Indian and international urban consumer straight from the remotest craft village may be, for a brief instant, considered justified.

“Sustainable fashion that ‘otherizes’ the village thrives on the carefully-constructed case that the village is stuck in the glorious past.”

This urban fascination for the exotic village is not a new theme; it has to do with the specific colonial history of India that has resulted in a seemingly eternal tightrope walk between tradition and modernity. This dichotomy is often juxtaposed with a rural—urban division that reinforces the image of a modern city as opposed to a traditional village. While a rising national awareness about the benefits of locally sourced, handmade, homegrown products does pitch a promising future for economic and social sustainability, it also runs parallel with a purpose of (re)locating India’s lost cultural identity in its traditional villages. A notion of the countryside retaining a more authentic India motivates contemporary Indian fashion to strike a balance between an externally adopted irrevocable modernity and its own “timeless” traditional past. Visual imagery of the village is often synonymous to unmatchable purity and a frozen image of time itself. In this vein, any association with the sepia-toned pictures of the “exotic” Other are meant to be synonymous to the same interests of fashion seeking an abnormal pause in time.

In other words, sustainable fashion that “otherizes” the village thrives on the carefully-constructed case that the village is stuck in the glorious past; a past that is a more authentic version of traditional India that was lost by urbanism. Far from bridging the gap, it is this very gap between the traditional past and the modern present that contemporary fashion banks on, to envision a hybrid sustainable future hereafter.

Sustainable India – a recap

A revision of history will reveal that traditionally, sustainability had always existed in India in many minor and major forms; we only now know the universally popularized English word for it—an amusing postcolonial reality. In Hindi, there is no specific word for sustainability; the closest synonym would be sthirta, which means “stability.” Likewise, art, craft and design were never separated in meanings; the Hindi word shilp is used to represent all three categories simultaneously, indicating a dynamic flow of conceptualization and occupation. Industrial designer Singanapalli Balaram states that it was not until the escalation of modern industrialization in Europe that the term “design” began to be used to address mass-produced industrial art.

Before the rise of the concrete jungles and the infiltration of industrialized products into the Indian economy, lifestyle was about an ecological harmony of humans and nature, and many of these forms of living still exist today. Whether it is the traditional way of having food served on a variety of leaf plates, or drinking lassi or chai from a clay mug, these are both environmentally friendly and economical.

Left: Contemporary designs of traditional leaf-plates (Source: Leaf Plates, Sustainably 2021); Right: Kulhad, the mug made of clay (Source: Environment-friendly ‘kulhad’, The Indian Express 2020)

Cow dung is used as biofuel as well as a disinfectant for the dusty ground in the villages. Water jugs made of copper provide a plethora of health benefits, along with keeping the water naturally cool in humid climates without a refrigerator. Coir from the coconuts is used to make mattresses and doormats, while the spines of the coconut leaves are bunched up to create brooms, proving a judicious use of locally-available materials. The traditional cot known as the charpai or khatiya is created by efficiently weaving jute or coir onto a wooden frame. The cot, Balaram notes, is exceptionally multipurpose—used for sitting, sleeping, drying utensils, red chillies, sun-soaking pickles or papadams; it is also impressively lightweight, which allows it to be mounted on a wall to conserve space when not in use. By definition, since design is termed as a “problem solving” activity by many design thinkers, an excellent example here is the Indian frugal concept of “jugaad” or an “innovative fix; an improvised solution born from ingenuity and cleverness” that is “practiced by almost all Indians in their daily lives to make the most of what they have.”

Left: Brooms made from the spines of coconut leaves (Source: Coconut Brooms, India Mart 2021); Right: The traditional Indian cot known as charpai or khatiya (Source: Luke Heather, Charpoy, Design & Make 2020)

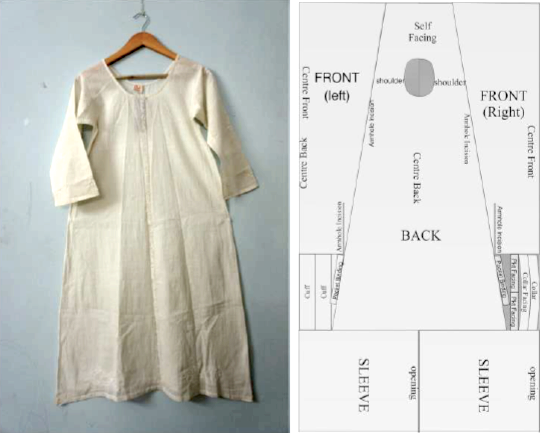

Particularly in the subject of clothing, Indian silhouettes such as the sari, dhoti and pagdi use fabric directly off the loom in different styles of draping, irrespective of the body shape or size. Similarly, research on dress history shows that cut-and-sewn garments such as the kalidaar kurta, choli, jama, salwar, churidar, seedha paijama and lehenga were traditionally constructed in Indian zero-waste techniques that utilize the entire rectangular piece of fabric. The Indian craft of Kantha originated and evolved as the simple technique of aesthetically repurposing worn out saris into quilts. Thriftiness of reuse was ingrained in the social culture of hand-me-downs, and good quality of products was in tune with the practice of preserving invaluable clothing for generations. The Indian paisa vasool (value for money) attitude was closely linked to longevity. Quite interestingly, almost until the beginning of the 21st century, a typical middle-class Indian mother (including mine) loathed gifts of children’s clothes that fit them beautifully, as kids are expected to expand fast and outgrow their clothes too quickly!

Left: The versatile draping styles of a Sari (Source: Illustration of different styles of sari, gagra choli & shalwar kameez worn by women in India, Wikipedia, 1928); Right: Kalidar Kurta (Source: Kalra and Bhandari 2015)

So, how is it that such lifestyles of sustainability—which existed in Indian culture long before the global mushrooming of the word itself—have been lost or overshadowed today? Why is sustainability portrayed as a concept out of our reach? How did this void emerge in the country’s ecosystem? To imagine a sustainable future, it is prudent to take a trip down to the sustainable past. A revision of India’s colonial history is extremely crucial to trace the dramatic shift in culture.

The British colonial era (17th century to mid 20th century)

When the colonizers infiltrated Indian cities with an imperial metropolitan culture, the village with its numerous artisans of diverse trades was often identified as the “Other.” Furthermore, as art historian and cultural anthropologist Saloni Mathur illustrates, India’s visual image was popularized through picture postcards that made their way into European homes. Such pictorial depictions intensified the distinction between a modern, “civilized” metropolis and its traditional, “primitive” colony. India came to be seen as a distant land that is meant to be explored and exploited for its “exotic” commodities.

Various art historians and postcolonial critics have written about the epitome of “otherizing” that took place during the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London. Indian crafts and textiles were praised for their exquisite quality and craftsmanship, while the machinery and tools on display were considered primitive in comparison to the advanced industrial technology of the West, and the craftsmen that produced them were looked down upon as a backward, undeveloped past version of the metropolis that needed to be “modernized.” In other words, Indian design that was culturally sustainable was isolated from its cultural context, and amplified and “Orientalized” on the global stage.

“As the foreign demand increased for designs such as the Indian buta, the motif was tweaked as per the tastes of the European market.”

Postcolonial theorist Edward Said, in his powerful books Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, offers an enriching debate on this, questioning the way aesthetics are seen as an independent function of culture, as a superficial layer exempted from the socio-economic-political spheres. Consequently, certain Indian textiles were commodified and a degree of value was assigned because of “the stamp of Victorian industrial consumption,” as Mathur sharply puts it. Not only was economic value created for crafts, but as the foreign demand increased for designs such as the Indian buta, the motif was tweaked as per the tastes of the European market, and popularized in the Scottish town of Paisley as original shawls from India, with an authenticity paradox. Soon, with increased industrial products that fulfilled the demands for Oriental lookalikes, the home-based manually-led industries of India suffered a deterioration. Writer and politician Shashi Tharoor reports this collapse of the native economy, asserting that Britain’s industrial revolution was built on the deindustrialization of India.

Addressing the evolution of contemporary Indian design therefore compels us to situate the historical design trajectory of “traditional” India that was presented under an international spotlight. The imperial visual culture further manifested in categorization such as “Indian culture,” “craft,” “tradition,” “village” and “artisan.” Mathur urges to examine the nation-state both in its colonial and postcolonial versions to comprehend the shift and the nature of its “culture diffusion.”

Postcolonial identity-making: The urban elites

A rising fervor of the newly independent India seeking a global ascension took over as the country set about to renegotiate its cultural identity and representation. Already deeply rooted in a capitalist economy, the postcolonial legacy of modernity was carried on by the “indigenous elites” who were trained in colonial art education but also had the responsibility of sustaining Indian cultural aesthetics. Thus, the birth of post-colonial modernism in India happened as a result of an identity crisis and the need of an artistic expression, as the progressive urban elites sought to establish what Mathur calls an ironic “balanced modernism.”

“As modern technology and science took a seat next to traditional ways, it was not a harmonious coexistence as it came with a cost: a significant decline of the artisanal communities.”

Meanwhile, parallel to the swift urbanisation, the Indian Government carried out post-independence projects to uplift the heritage industry which further intensified the otherizing, as the sanctity of rural India was to be preserved as India’s traditional past. The dichotomy of urban and rural India inadvertently continued post-independence. While the formerly established global admiration for Indian textiles and crafts created a market economy for exports, the same passion for crafts somehow grew dull within the local market, and only worsened as a result of the liberalization policies that boosted modern consumerism. Suddenly, everything was to be modern! Balaram highlights that, as modern technology and science took a seat next to traditional ways, it was not a harmonious coexistence as it came with a cost: a significant decline of the artisanal communities.

Along with rapid strides in technology during free India’s real encounter with modern industrialization, the decades that followed independence also led to the establishment of design institutions that offered professional design training. The National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad was the first in this regard, followed by The Industrial Design Centre (IDC) at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Mumbai, and The National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), New Delhi. According to design educator Ashoke Chatterjee, the driving ideals that were laid out for and by the pioneering NID could only be partially met owing to the liberalized economy of the 1980s. The mission of evaluating a “good life” relevant to the socio-political-economic reality of India was sidelined; “design” as a modern discipline was expected to bridge the gap between the growing consumer needs and the existing small, medium, and large scale cottage industries. This kind of separation of art-craft-design from its contextual significance can be seen to have resulted in a failed understanding of sustainability ingrained in Indian culture. Cultural sustainability was compromised when India (re)negotiated its design identity in a race for modernity.

With the upswing of fashion, especially since the 1990s, there arose two sets of consumer tastes that were in sharp contrast. One segment of the market was dominated by super-Westernized modernity, while the other segment romanticized the bourgeois fantasy of contemporary fashion with a nostalgia for a lost royal identity. The latter set a precedent for the storyline of sustainable fashion in the current times that glamorize the lost glory of authentic India.

From ‘sasta, achcha, tikau’ to sustainable fashion!

The above words stand for a popular Hindi consumer-phrase for “economical, good quality, durable,” a sustainable thinking that was ingrained in the Indian mindset before the escalation of mass consumerism. Such cultural expressions serve as constant reminders to acknowledge that sustainability is, indeed, not a novel concept in India at all.

To begin with, sustainability and fashion are two opposing forces. While sustainability is informed by cultural self-sufficiency, fashion flourishes on temporality. What was once a classist practice, with the elites being the social class that introduced new fashion that trickled down to the masses; today, fashion is produced for all classes without social distinction. As a result of the omnipresence of what sociologist Zygmunt Bauman calls a “perpetuum mobile” of fashion, sustainable fashion itself becomes an oxymoron, says design researcher Otto von Busch. Similarly, anthropologist Arjun Appadurai in his 2013 book The Future as a Cultural Fact shares a fascinating assessment of the uncontainable nature of fashion, by also analyzing the distinction between the functions of “design” and “fashion.” Both, he says, serve as infrastructures that provide combinations of socio-cultural “contexts” that render relatability of an object to humans. While, as he states, fashion comes up with endless contexts for objects, design puts a regulation on the possibilities by delivering “credible and grammatical” forms of contexts.

“Sustainability and fashion are two opposing forces. While sustainability is informed by cultural self-sufficiency, fashion flourishes on temporality.”

This ephemeral quality of fashion produces a larger complexity in the cultural setting of India, as the very availability of plentiful of sustainable indigenous craft practices makes them vulnerable to the “planned obsolescence” of fashion. Whereas historically, Indian textiles and clothing practices have characteristically been sustainable, in today’s postcolonial capitalist economy, the pursuit of achieving economic, social and environmental sustainability in (over)producing fashion gives rise to a different crisis: an unsustainable cultural climate. Though a plethora of design practices have been introduced to address this umbrella term in various levels of feasibility, there remains a looming threat of colonially inherited legacies that manifest in the contemporary practices of capitalizing on culture and otherizing the Indian village.

For instance, in 2019 the Indian state of Kashmir was in extreme political unrest after the Government ordered a media blackout and unwarranted detaining of innocent citizens. At the same time, Raw Mango, a high-end designer label that is popularly recognized for its “beautiful campaign photoshoots,” launched a collection based on the lost royal heritage of Kashmir. The label was highly criticized for its neo-orientalist ideology of capitalizing on the culture of Kashmir with an exoticizing gaze, ignoring the state’s harsh current reality.

Similarly, Shilpa Sharma, the co-founder of Jaypore, a retail brand that uses indigenous crafts, highlights in an interview that the international appreciation garnered by Indian textile traditions point at the need to revise our perception about crafts, to indulge in “these living, breathing fabrics and embellishments [...] with modern nuances and helpings of expertise.” While she encourages Indian designers to explore the potential of a modern outlook, she strongly urges that “India needs to reclaim its heritage as the West is walking away with it,” further emphasizing yoga, Ayurveda and the goodness of turmeric!

“Fashion primarily indulges itself in the art of storytelling through clothes; and such stories that involve cultural ingredients have the ability to endure, as well as alter narratives.”

The thought not only reinforces the general “modernistic” mindset of sustainable brands that address Indian culture and crafts with vested interests, but also reflects—what I call—a typically “outward and inward” figurative gesture, of perpetually peeking out and imitating the “West.” Fashion primarily indulges itself in the art of storytelling through clothes; and such stories that involve cultural ingredients have the ability to endure, as well as alter narratives. Sustaining sustainability itself seems a puzzling challenge unless these recurring patterns of coloniality are identified as a cultural threat.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold sheds an intriguing light on the definition of “material culture.” He suggests that the material or materiality of the artefact matters least, as it is culture that wraps itself over the world of material objects, defining and shaping them without engaging with their interior. It is culture that gives meaning to material things. Therefore, amidst the debates on the numerous sustainable practices lies the subject of culture: what forms of sustainability are culturally crucial and favorable under a backdrop of the socio-political-economic context of the country, especially in creating the oxymoronic sustainable fashion? What kinds of cultural elements and images are we preserving in the quest for materialistic sustainability, that furthermore shapes the very culture?

“As Indian fashion brands continue to market the village in romanticized poetic terms, this rising style of self-orientalism [...] has serious cultural implications.”

The dilemma of aiming for sustainable fashion in India lies within the entanglement of generating employment, preserving languishing crafts and creating lasting clothing. Fashion brands that address this triangulation with approaches of large-scale production often envision large-scale social impact. Following an industrial process, handcrafted sustainable clothing is made to adapt to methods of standardization—an industrial uniformity that is diametrically opposite to the beauty of irregularities in craft products created by diverse hands. While these efforts to organize the “unorganized” crafts sector and make it adapt to the contemporary fashion market have favored some craft communities to build larger capacities of production, such noteworthy but ambitious missions of “creating livelihoods” have also resulted in preserving the most commercial versions of traditional crafts. As Indian fashion brands continue to market the village in romanticized poetic terms, this rising style of self-orientalism that typically erases the borders between the product on sale and the culture at display has serious cultural implications. If a sustainable present and future in Indian fashion is to be imagined, it must be centered in decolonial thinking with an uncompromised cultural sensitivity, to redefine progress and values.

Laya Chirravuru (she/her) is a fashion designer from India. She is an alumnus of the National Institute of Fashion Technology, Delhi. Having worked in the retail fashion industry in India, she is currently making headway into the field of research. Her passion lies in the areas of sustainability, culture studies, and design anthropology. At present, she is pursuing a master’s degree at the Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau, Germany.

Title image: Ensembles by the Indian designer label Eka, shot in the location of a desert landscape (Source: Casa Noor)

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain fellowship.