Squashed between other women with one leg dangling outside the bus, I keep my eyes peeled for the next available seat. Finally! The makeshift seat on top of the hot engine is free—I must move quickly to claim it. I climb onto the engine, take a breath, and wonder with frustration: why do we have to endure this undignified situation every day? This is not the first time I’ve asked myself this. Growing up without a car in Karachi, I became accustomed to the experience of using public transport—the tumultuous G-7 local public bus to Karachi University was part of my daily routine.

Karachi is Pakistan’s largest city and economic hub, with more than 20 million people, including migrants and refugees of multiple faiths, ethnicities, and languages. Against the backdrop of this diverse tapestry, life in Karachi is chaotic and appears to be ruled by unpredictability, even though there is a sense of order to this madness. After Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the city’s population increased rapidly. However, with a fragmented government, the development of an affordable mass transit system was not a priority, and traveling in crammed buses is still the typical way to commute.

This reality is not unique to Karachi. All over the world, navigating public space has never been easy for women. Having to dodge harassment and unsolicited attention is mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausting. When these lived experiences are not taken into account, cities become gendered spaces that limit women’s freedom of movement. I have walked the roads, footpaths, and footbridges on my own—but never at ease. This makes me wonder: is this the only way?

“All over the world, navigating public space has never been easy for women. Having to dodge harassment and unsolicited attention is mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausting.”

In her book Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World, feminist geographer Leslie Kern notes that feminist visions of a city are not a new ideal, but that they often go unnoticed. She describes them as “pockets of resistance or alternative ways of organizing care, work, food,” and argues that these are “sites of possibility for a broader, transformative vision.” What patterns of interaction are there in Karachi that might reveal women’s unspoken resistance? And, in which ways can the city become a safe and inclusive environment for women and other marginalized communities?

Rickshaws, women, and the city

There are several forms of public transport services available in Karachi: buses, taxis, mini-buses, rickshaws, and Qingqi. Rickshaws and Qingqi are informal three-wheeler paratransit vehicles found in many South Asian countries that have filled the gap within local transit systems. Although they are more expensive, rickshaws are the second most popular form of transport used by women after buses, as they provide door-to-door services and, thus, a higher sense of safety. Similarly, Qingqis are a cheaper alternative because they can seat up to six people who can split the fare; however, these only work specific routes and do not provide separate seating for women, as local buses do. Public transport (and public spaces in general) in Pakistan are gender-segregated; social norms dictate that women sit on one side and men on the opposite, although this does not guarantee safety for women who still face routine harassment. Gendered social norms such as this are embedded in the fabric of how women navigate the city differently than men, further alienating their experience in public spaces.

Interviews with five male-identifying rickshaw drivers corroborated that their largest user base was women. They clarified that this is not due to them making gender-based distinctions but to women offering them higher fares—a strategy that, while beneficial to some, simultaneously relegates low-income women to traveling by Qingqi, even though they would prefer rickshaws. The common assumption is that rickshaws are a low-cost mode of transport, but their usage is actually a luxury highly dependent on class. On the other hand, men do not need to prioritize safety over budget, so they benefit from cheaper forms of transport such as buses and motorbikes. Therefore, whether a woman travels by car, bike, or bus, each is a unique experience marked by the external differences offered by each mode of travel. The resulting specific commuting patterns and behaviors highlight the biases and discriminatory attitudes towards marginalized members of society.

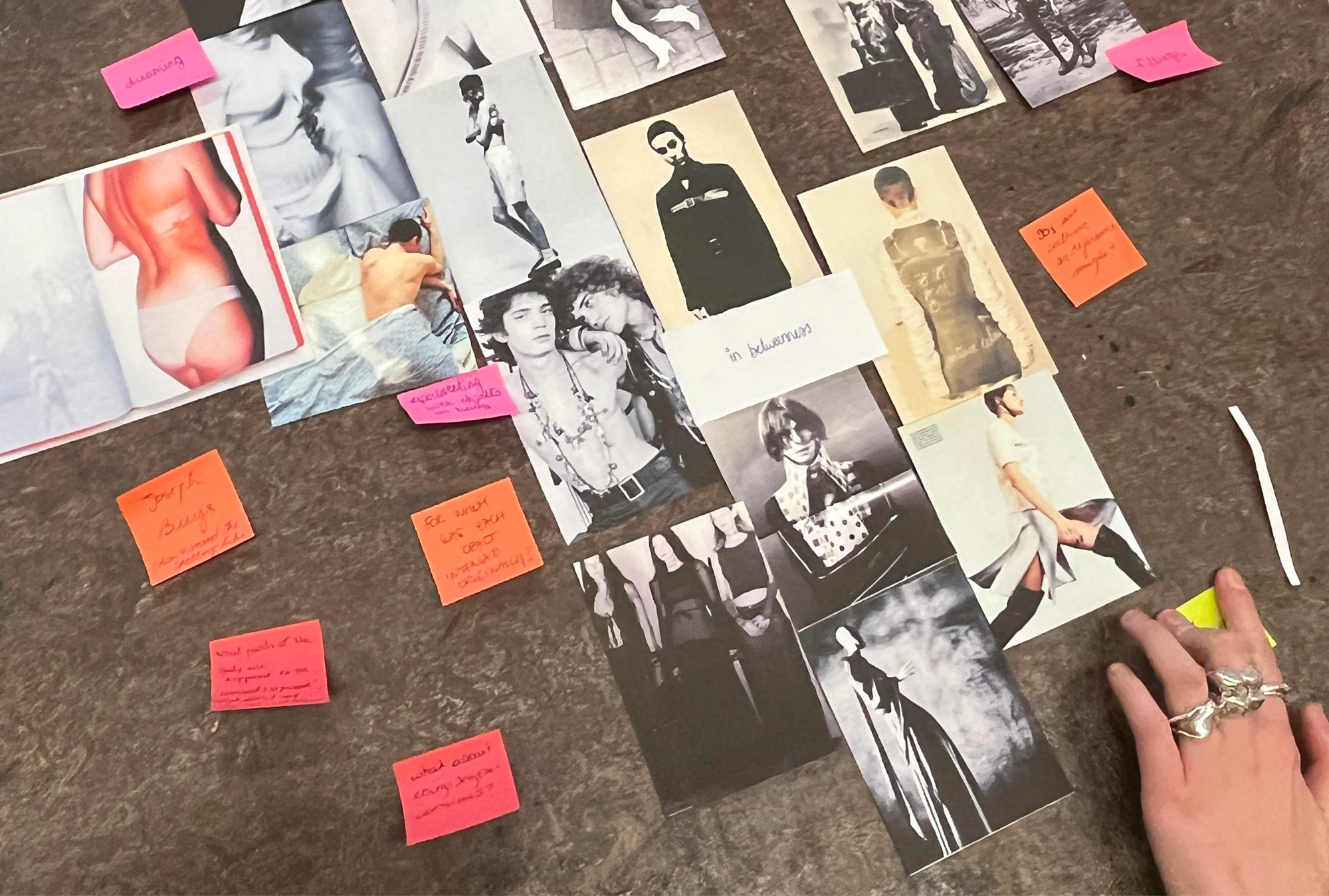

Women’s particular experiences are a means of knowledge production, and their positionality, a means of scientific inquiry. In this way, centering multiple feminist stances on cities is a way of challenging the status quo and untangling regimes of power. As the oft-cited popular feminist slogan states: “The personal is political”—moving in public spaces has always been an act of resistance, and so is the writing of this essay. I conducted several online surveys and informal interviews with a diverse set of women across Karachi, using a wide range of factors including income, age, occupation, ethnicity, and localities to probe how they navigate the city through the usage of public transport, map their commuting patterns and behaviors, and thereby broaden our understanding of gendered daily commutes.

In a conversation with Aradhiya, a local transgender woman, she reflected on her pre- and post-transitioning experience with respect to local transport. Aradhiya is in a unique position of witnessing firsthand the mechanisms of social exclusion that make traveling in the city an embodied gendered activity fraught with uncertainties for marginalized women. After transitioning, she had a change in both her thinking and her behavior. She explained that she is not able to ride bikes, travel by buses, or walk on the road anymore; she has now acquired an instinctive wariness—a gut feeling for detecting potential danger from strange men. She now follows many safety strategies common among women, such as choosing rickshaws as the preferred mode of transportation—ideally, with the neighborhood driver instead of an unknown person.

“[Aradhiya, a local transgender woman,] explained that she is not able to ride bikes, travel by buses, or walk on the road anymore; she has now acquired an instinctive wariness—a gut feeling for detecting potential danger from strange men.”

Similarly, cisgender women said they had developed a keen instinct to gauge by the driver’s face whether he is reliable or not. It is also crucial for some that the driver knows his way around the city. In this way, they would avoid being stranded alone in the rickshaw in an unfamiliar area. Women prefer to stick to familiar routes, even if it means taking a long way, and rickshaw walas are cognizant that cities are unsafe for women, so they usually ask for their permission before taking any alternative or shorter route. Unsurprisingly, many women consider their escape strategy; an unspoken safety factor is that, since a rickshaw is an open vehicle, it would be easier for women to jump out in case things take a dangerous turn.

From a young age, women are taught to be hyper-aware of their surroundings. Do men face the same mental burden when traveling by public transport? According to the rickshaw walas I interviewed, men do not have any such concerns. Their priority is reaching their destination on time through whichever route: “Kahin se bhi le jao bus jaldi pohcha do” (“Take whichever route you want, just get me there quickly”), they say.

Navigating urban spaces

The survey revealed Google Maps to be the most popular digital app choice for traveling to unfamiliar destinations. However, the use of Google Maps depends on smartphone possession, which makes it not viable among all social classes. Also, the app cannot update promptly enough because of the city’s unpredictable nature, and it does not include information about the safety of a particular route. How do women who do not or cannot rely on digital devices travel to new or unfamiliar destinations?

Commuting is a form of embodied knowledge. Embodied knowledge is born out of bodily experiences in the material world and a habit formed through physical repetition. In this context, mobility is essentially a movement of the body. But movement does not happen in isolation and is intricately connected to body and identity. Similarly, mobility by way of transportation dictates how much an individual is able to freely move as a way of wielding their right to public space. What is an everyday average Karachiite’s embodied experience of navigating and moving through the city like?

“Mobility by way of transportation dictates how much an individual is able to freely move as a way of wielding their right to public space.”

Karachi lacks a well-defined transport map, so it is common for locals to give directions according to landmarks. The shared response among women regarding how they reach unfamiliar destinations was that they either use common sense, ask local passersby and shopkeepers, or call their family members. Rickshaw drivers rely on similar strategies; they ask local shopkeepers or fellow rickshaw-walas, thereby confirming that commuting through embodied knowledge is a widely prevalent practice in Karachi.

Behaviors, habits, and self-reliance tactics such as these point to a new way of thinking. Though it is clear that both commuters and rickshaw walas in Karachi have developed a great capacity to overcome the shortcomings of a tricky (or lack thereof) mass transportation system, I ask myself, are design interventions needed? Canadian anthropologist and design ethnographer Anne Galloway points at the need to recognize that people are sometimes “okay living with contradictions.” Instead of rushing to design an intervention, it is worthwhile to pause and reflect on how and why people have made peace with the problems they face, she explains, “because it allows for other things to emerge.” Though there is an evident reliance on digital navigation apps, this is not always the answer—mutual care and willingness to help often supersedes communication and navigation technological norms that are considered integral to our social day-to-day lives.

Caring in Commuting

Familiarity is a key component of safety. Nearly all women I spoke with prefer hiring the neighborhood rickshaw wala. Rickshaw drivers often make one area of the city their adda (base) for many years and become acquainted with everyone in that neighborhood. “I know about my driver; he lives near my apartment. I know about his family too,” explains one woman. The practice of choosing the same rickshaw wala is, in a way, akin to having one’s own personal driver.

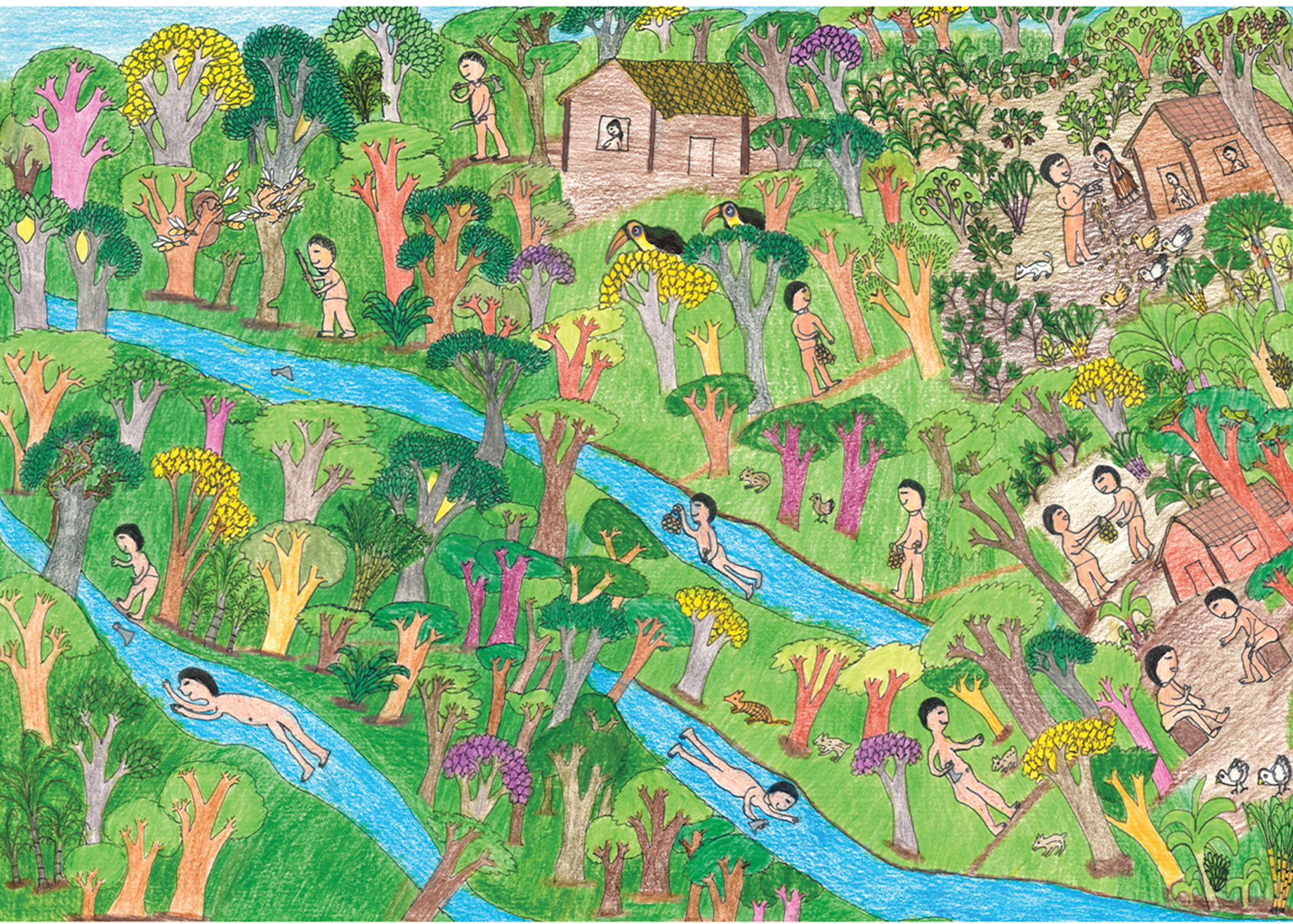

Women also carpool together, as in the case of Fehmida*, a domestic helper who commutes in Qingqi with six other women from her neighborhood. Fehmida contends that traveling together as a pack, having each other’s back, and being acquainted with the driver gives her and the other women a quiet sense of confidence. Such creative capacity to shape something for their need of safety, in this case through making private use of something public, signifies a form of urban appropriation. It is a reflection of the resilient spirit of the marginalized people who seek innovative ways to redefine gendered transport—an instance of world-making.

Similarly, one could argue that there is a form of world-making taking place between passengers and drivers in every such commute; a world based on mutual trust and care. When drivers caution their passengers to keep their phones safe inside their handbags, when they ask for permission before taking alternate routes, or when women warn them about broken roads, this highlights a particular sense of care between people.

“One could argue that there is a form of world-making taking place between passengers and drivers in every such commute; a world based on mutual trust and care.”

Karachi’s roads and traffic can quickly take a turn for the worse at any given time. It could be a result of an unexpected sewage leak, urban flooding caused by rain, an unannounced political rally or a protest, or a combination of any of these factors. In most cases, word of mouth and a quick scroll through social media work much better and faster than news conveyed through TV news channels. Concerned citizens share pictures and videos on Facebook groups like “Halaat Updates,” cautioning others to avoid specific routes. Similarly, quick updates are sent via WhatsApp messages and phone calls among rickshaw drivers.

In a system that works against marginalized peoples, the spread of information through unofficial channels speaks of a deep sense of community and care for the well-being of others. Karachiites display a generosity and a level of kindness that people from other Pakistan cities have lauded as something unique. One of the rickshaw drivers I interviewed mentioned that he does not keep a phone, and I asked if that caused him any trouble. He said it depended on my perspective: while he admitted that he would be unable to call a mechanic if his rickshaw broke down, he would always manage to find somebody willing to tow his vehicle to the nearest repair shop. These acts and visions of care have the capacity to imagine, in Kern’s words, “new feminist urban worlds, even if those worlds only last a moment, or exist in one little pocket of the city.”

Curbing the city

Women’s different strategies to keep themselves safe are often called “coping mechanisms,” or choices made out of majboori (a sense of helplessness and need) in response to a challenging situation beyond their control. Although this might imply a lack of agency, in all the conversations I had with the women I interviewed, I sensed a strong will and a determination not to let these mechanisms of social exclusion become a rukawat (hindrance) in their everyday life.

There is a fine line between nurturing marginalized women’s acts of defiance and romanticizing their struggles. How can I talk about Karachi without neither denying its harsh realities nor idealizing its ways of resistance? Karachi is made up of complex everyday interactions, and communal practices of care carried out naturally in urban spaces. The strands of generosity of spirit displayed by the people of Karachi have gently weaved themselves into the fabric of violence and gendered socio-cultural norms. This does not nullify the harsh realities of living in the city. On the contrary, unpacking the issues women face adds a more profound, layered perspective to the inefficacy of the city’s gendered infrastructure.

“There is a fine line between nurturing marginalized women’s acts of defiance and romanticizing their struggles. How can I talk about Karachi without neither denying its harsh realities nor idealizing its ways of resistance?”

That being said, throughout the writing of this article, there was continuous news of mind-numbing, senseless violence against women coming out of Pakistan, which filled me with trembling rage and made me question the futility of my research. Between inner monologues of anger, I wondered if I was being naive and idealistic. Are these feminist practices and acts of urban resistance, or just basic survival strategies? I do not have an answer to this yet. Still, I know that this uncertainty is precisely what keeps my research alive and moves me forward in my journey of nurturing, growing, imagining, and creating alternative spaces for expressing our feminist right to the city.

I dedicate this to all the brilliant women I have had the pleasure of knowing and collaborating with. I am indebted to everyone who opened their hearts, shared their stories, and allowed me a glimpse of their understated fierce resistance, which forms the core of this research. Finally, this is also an ode to my city and its people, to our shared struggles, joy, and despair.

*Names have been changed for privacy.

Zainab Marvi (she/her) is a Pakistani designer, researcher, illustrator, and educator, based in Germany. Having lived and worked in Karachi, Pakistan, a common thread in her work revolves around women in public spaces and feminist cities, particularly how marginalized communities perceive and navigate the city.

Coming from a graphic design background, Zainab always strives for a multi-disciplinary approach, including visual design toward gender, urban spaces, and feminist geography. With a penchant for having her fingers in a lot of pies, she is presently involved in a fellowship on investigating women’s global history in horror cinema through videographic essays. Zainab also researches and teaches at the Bauhaus-Dessau Master program, a course on critical mapping as an activist and speculative tool for mapping the past, present, and future of the world(s) we live in. Her research is anchored in feminist theories, and research methodologies and how they inform design research approaches in the Global South.

Title image: Asian Development Bank (Source: flickr)

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain Fellowship.