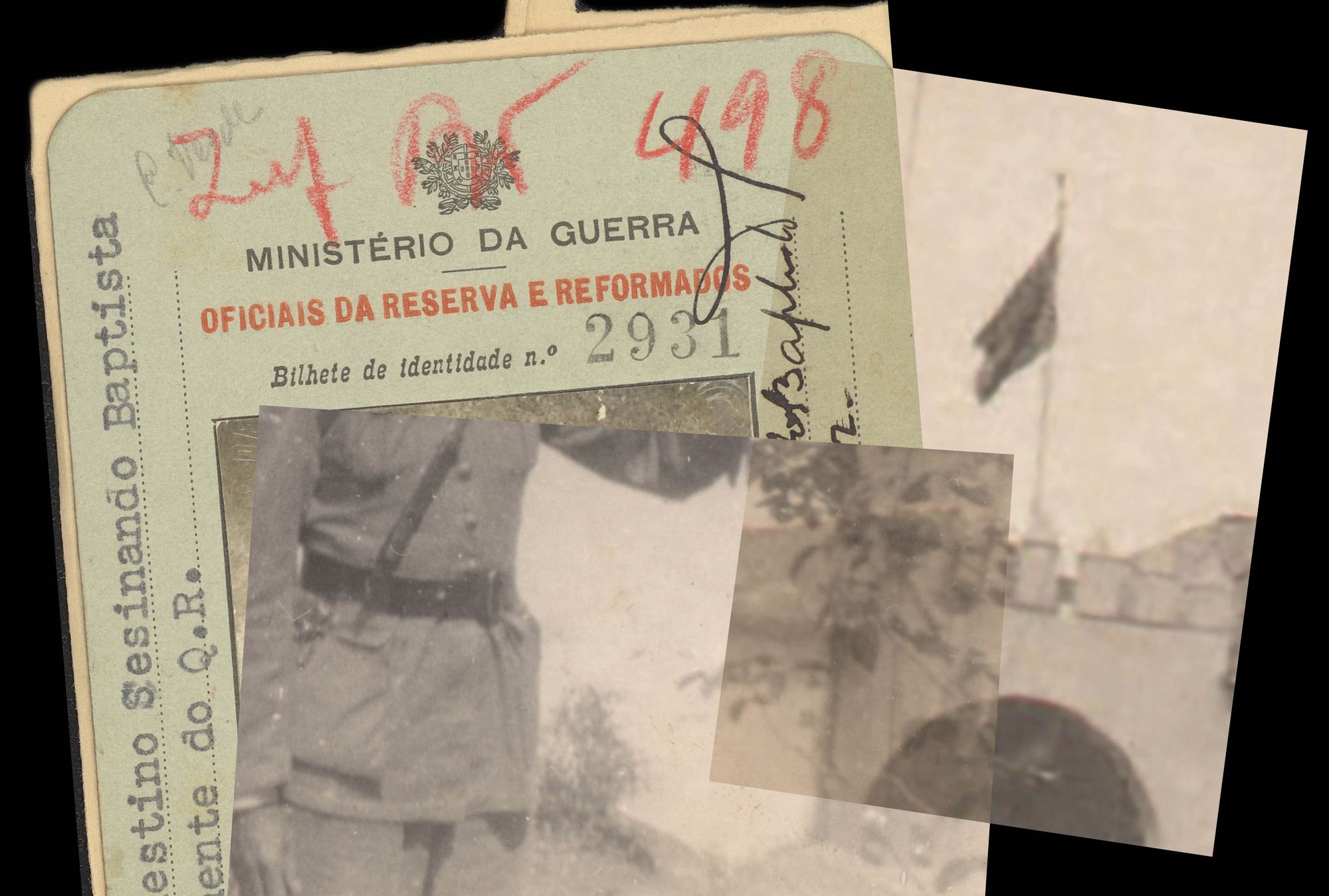

Searching for past feminist Yiddish periodicals fills me with a void. This void has been with me for a long time; it accompanied me while growing up in a family of Eastern European Holocaust survivors. I missed the world of the large Ashkenazi diaspora, which was exterminated by the Nazis against the backdrop of silent indifference, decades before I was even born. I missed its culture. Its languages. Its writings. And its press.

“I missed the world of the large Ashkenazi diaspora, which was exterminated by the Nazis against the backdrop of silent indifference, decades before I was even born.”

Growing up in Poland, I would browse through the glossy issues of Midrasz, a monthly cultural journal that was published between 1997–2019; or the socialist leaning Das Yiddishe Wort דאָס ייִדישע וואָרט Słowo Żydowskie (The Jewish Word), to which my mom subscribed. Słowo Żydowskie has been published since 1946 by the Social and Cultural Society of Jews, and it is still the longest existing Jewish periodical in Poland. Neither of these publications was even remotely feminist, nor did they mention the Talmudic gender categories, which I vaguely knew existed. Recently, I embarked on a journey to trace the beginnings of the feminist Yiddish press. I thought that perhaps, in the pages of some periodical unknown to me, I could find out more about the Jewish performance of gender.

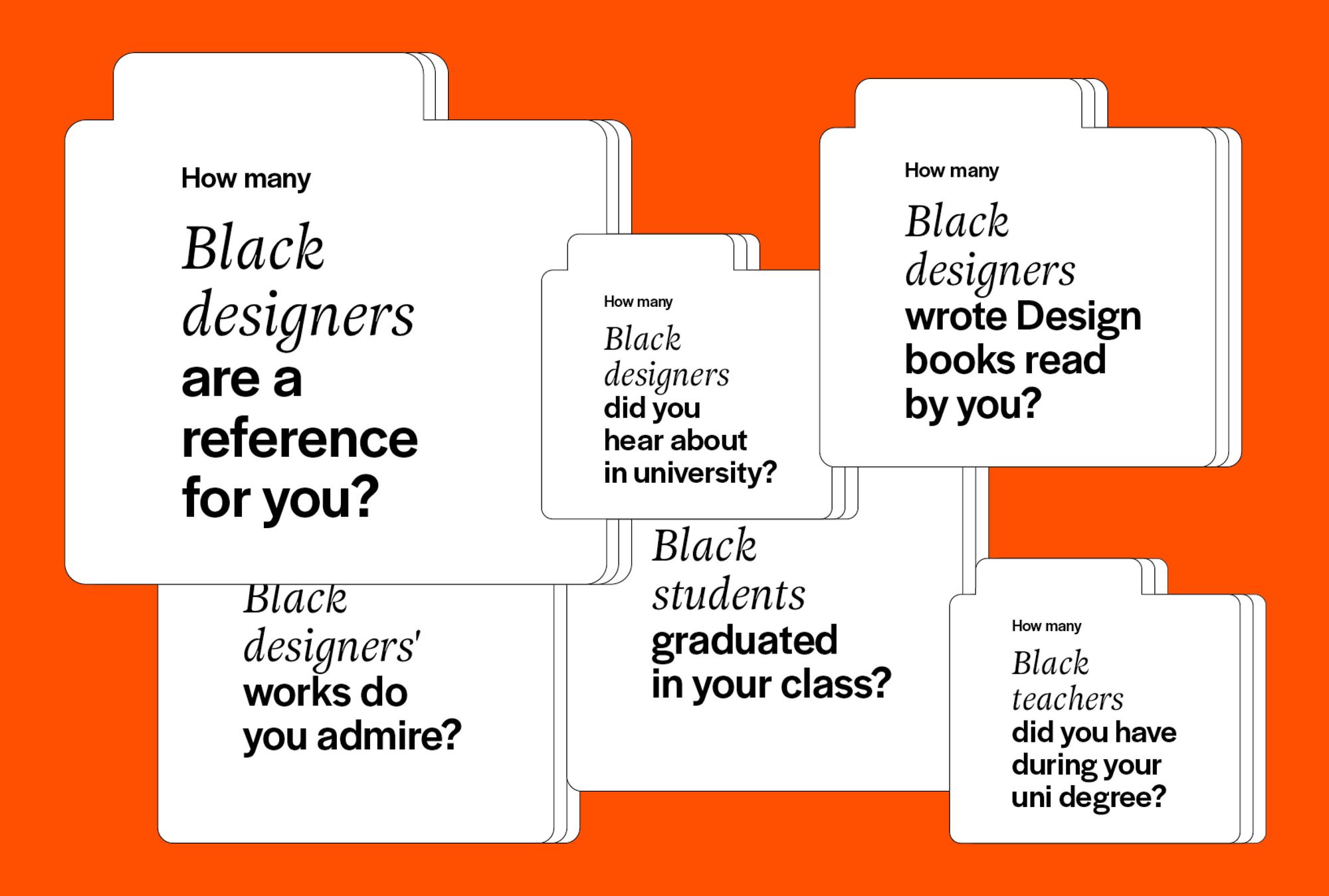

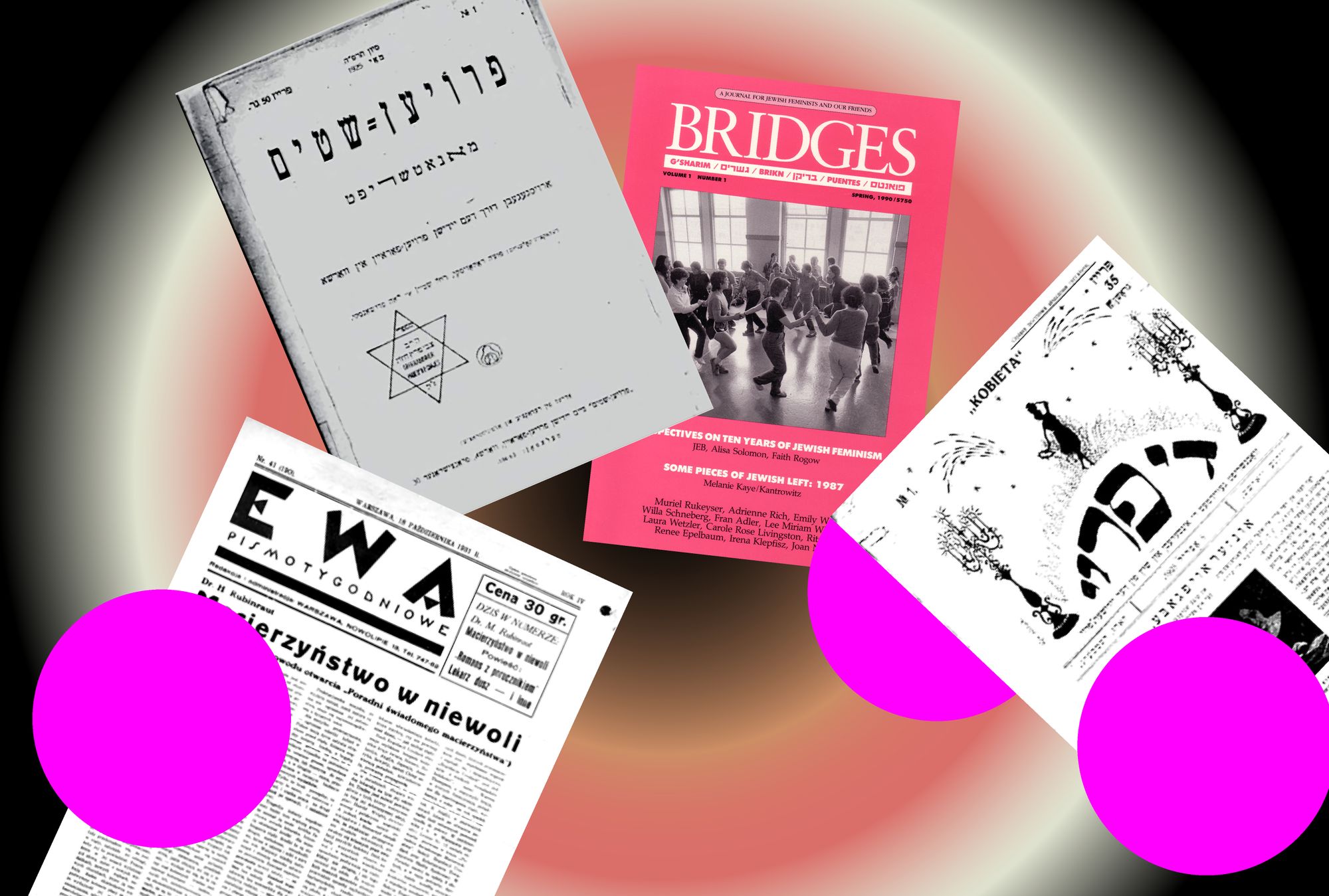

Prewar Poland had a vibrant Jewish press scene comprising 130 daily newspapers and magazines in Yiddish, 28 in Polish, and around 20 Hebrew periodicals; these made up almost 7% of the titles and periodicals in the country. The online archive of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw captures this diversity: it includes daily newspapers from a wide political spectrum, magazines on theatre and literature, children and youth periodicals, pedagogical journals, and publications focused on culture, politics, art, and even astrology. Through their online archive, one can browse through socialist, communist, zionist, and liberal periodicals; but there is not a single feminist publication. But what does this absence reveal — that there were no feminist periodicals, or that they were simply not archived?

“But what does this absence reveal — that there were no feminist periodicals, or that they were simply not archived?”

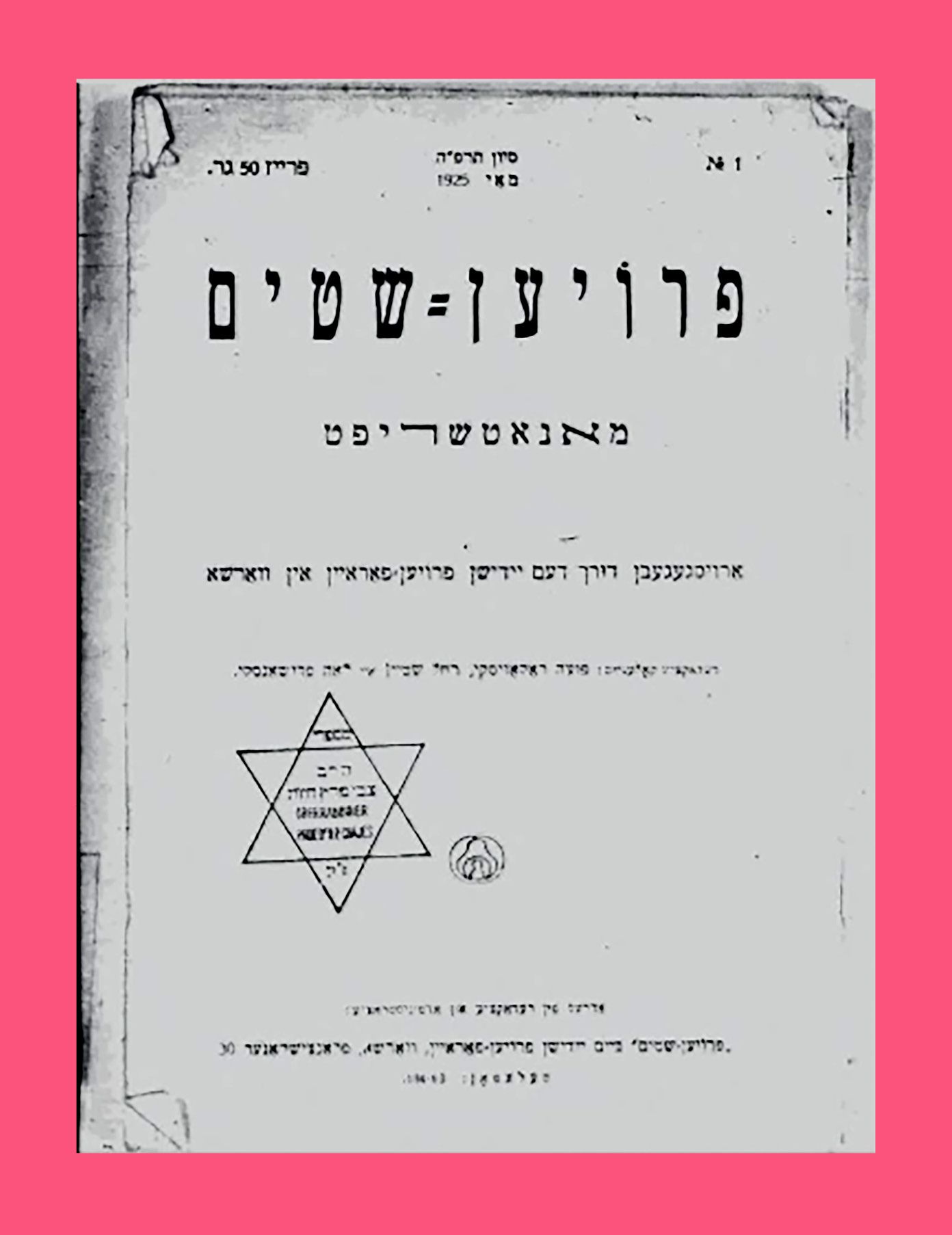

“The doors of the Jewish press are still strongly shut for us women!” complained Pua Rakovski, Rokhl Shteyn, and Lea Proshanski in the first issue of Froyen Shtim פרויען שטים (Women’s Voice), a black and white weekly newspaper that started circulating in May 1925 in Warsaw. According to Yiddish scholar Joanna Lisek, the objectives of the periodical were clear: it demanded equal rights for Jewish women, postulating that “the woman has to play the same role and make the same contribution as the man.” Also absent from the Jewish Historical Institut’s website was Froyen Shtim, which stopped being published abruptly in the same year.

Froyen Shtim adhered to feminist rhetoric from the first wave of feminism, and was steeped in nationalist, colonial, and Zionist rhetoric. Its cofounder, Puah Rakovsky, was an especially controversial figure. She was a Jewish women’s rights activist and educator on the one hand, and an adherent supporter of the Zionist colonial-settler movement in Palestine on the other. Without a doubt, her work promoting literacy and formal secular education among mostly working class Jewish girls and women in Poland was important. However, her involvement in the World Organization of Zionist Women—WIZO and other nationalist efforts that led to the dispossession of Palestinian people including many women—begs the question: can Rakovsky even be considered a feminist? Even though she self-identified as a Zionist feminist, Palestinian activists and scholars urge us to see Feminism as a movement striving towards equality and Zionism as a colonialist and racist ideology, which make both politically incompatible.

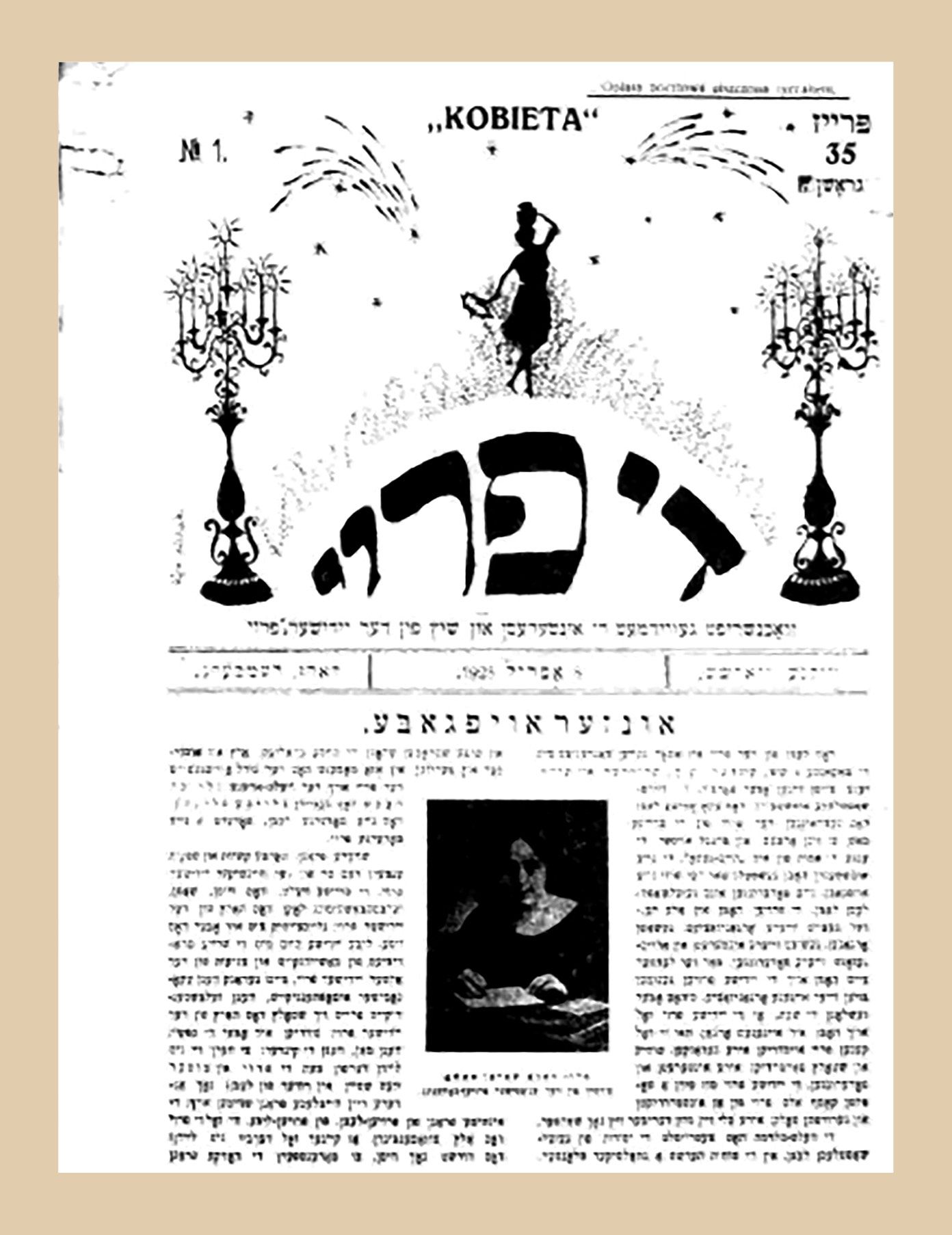

Khana Blankshteyn, Yiddish writer from Vilnius and the editor of Di Froy 1925-1933 די פרוי (“The Woman”), represents a different political stance. She was affiliated with the Jewish People's Party ייִדישע פֿאָלקספּאַרטײַ, which demanded cultural and political autonomy in the Jewish diaspora, instead of being under the rule of Palestine. On the pages of Di Froy, a weekly paper distributed across Vilnius, Warsaw, Lodz, and Krakow during the 1920s, there is a concern voiced about the preservation of Jewish cultural and religious identity. The author recognized the triple struggle of Jewish women: their struggles due to gender; due to being members of an oppressed ethnic group as well as a personal, internal one; and due to Jewish women’s wish to preserve a traditional Jewish household filled with love and care, while also being attracted to the modern model of equal rights.

“…the triple struggle of Jewish women: their struggles due to gender; due to being members of an oppressed ethnic group as well as a personal, internal one; and due to Jewish women’s wish to preserve a traditional Jewish household filled with love and care, while also being attracted to the modern model of equal rights.”

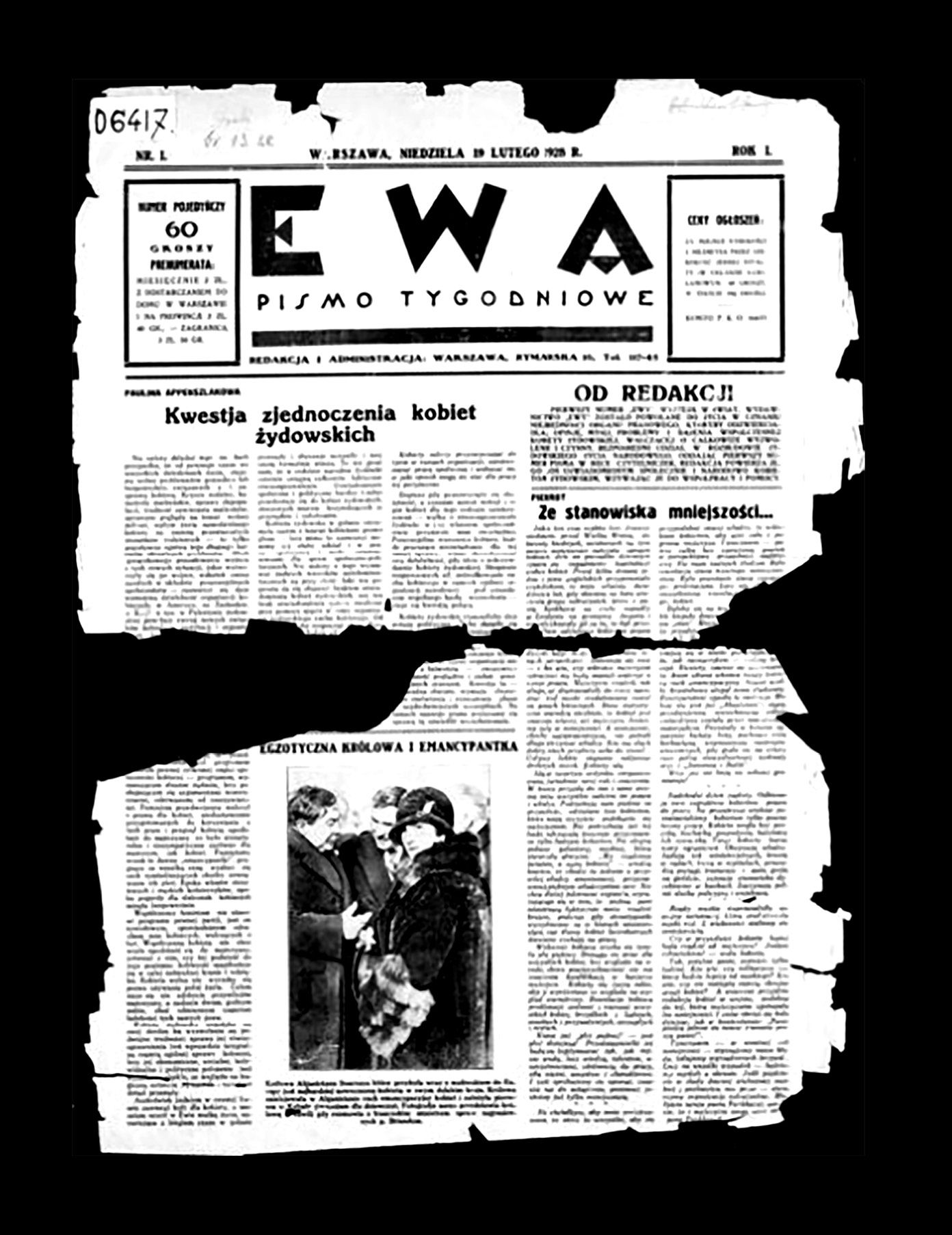

I haven’t yet found digital scans or physical copies of either Froyen Shtim or Di Froy; I’ve only extracted information about them from scarce scholarship on feminist discourse in women’s Yiddish press. One article’s footnote mentioned Ewa, the Jewish Feminist Weekly published in Polish from 1925–1933 and edited by Pola Appenszlak and Iza Wagner, which led me to the digital archive of the Polish National Library and an almost complete collection of scans.

Ewa was bold. “Captivity of the Motherhood!” screams the headline of the October issue in 1931. Vocal about reproductive rights, the paper continuously raised the issues of birth control and women’s freedom of choice, demanding legal, safe, and free abortion as well as comprehensive sexual education. It’s a battle that Polish feminists are still fighting for today, ninety years later. Appenszlak strongly motivated her readers (other Jewish women) to exercise their right to vote. As a vocal pro-abortion activist, she also encouraged sexual education and planned parenthood. Like many of her Jewish contemporaries in Poland, Appenszlak failed to see the Jewish feminist cause beyond ethnic lines, and was also an adherent Zionist, succumbing to its colonial-nationalist discourse.

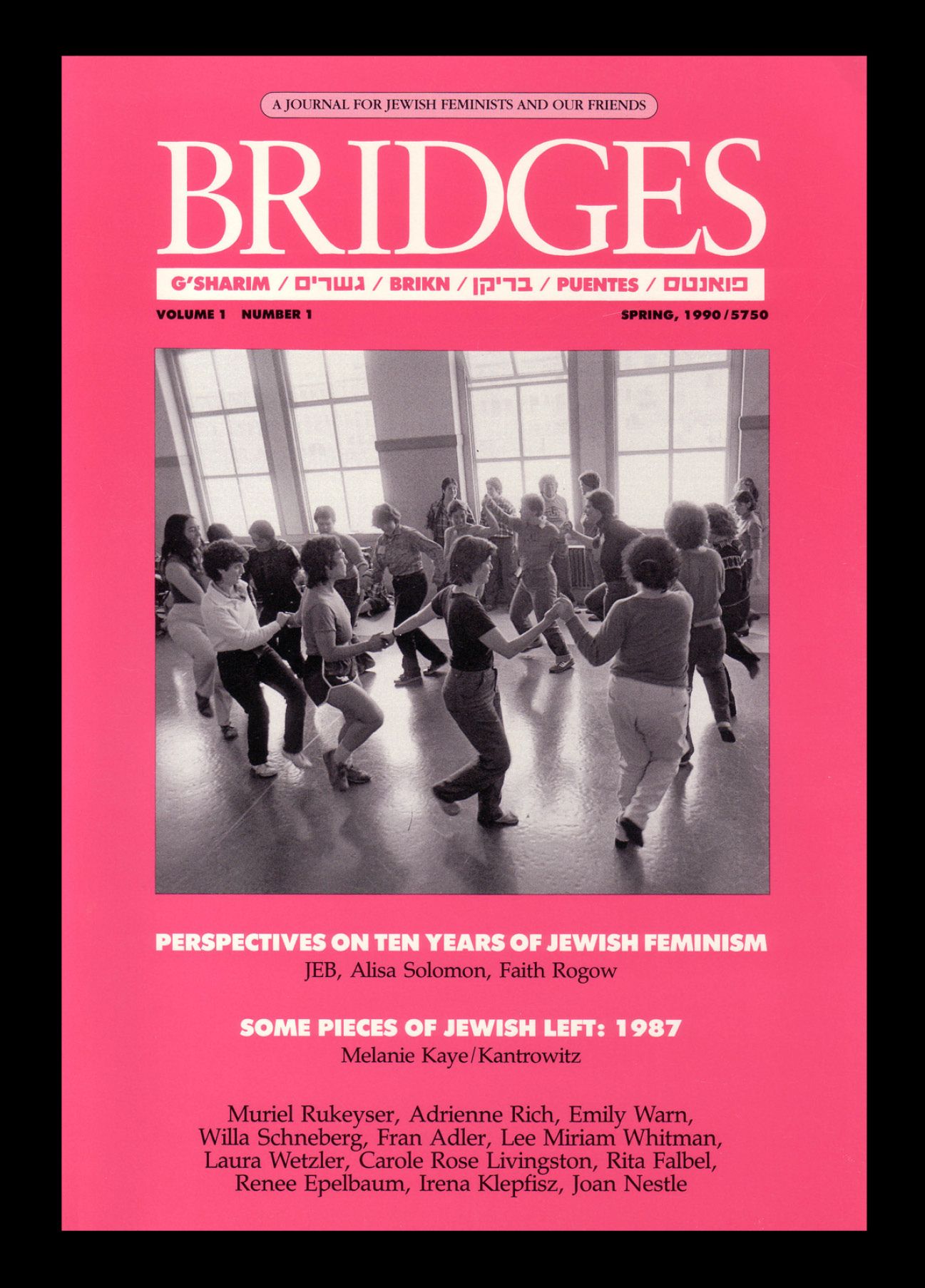

“We only have one issue of an American magazine called Bridges, from 2009,” replied an archivist from the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, in response to my inquiry about feminist or womxn’s periodicals. Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends was a bi-annual publication produced from 1990 until 2011. It supported a multiethnic feminist movement, integrating analyses of racism and classism into Jewish-feminist thought, as well as connecting readers across generations and languages. Politically, it was rooted in Diasporism, seeing “Jewish home” wherever Jews reside, instead of striving toward a nation-state. It was also a periodical engaged in fostering Jewish values of social justice and Tikkun Olam (in Hebrew “repair of the world”), bridging between different Jewish identities and activism. Bridges published archival writings, also of Yiddish feminist press. And one article discussed Jewish approaches to gender. Finally!

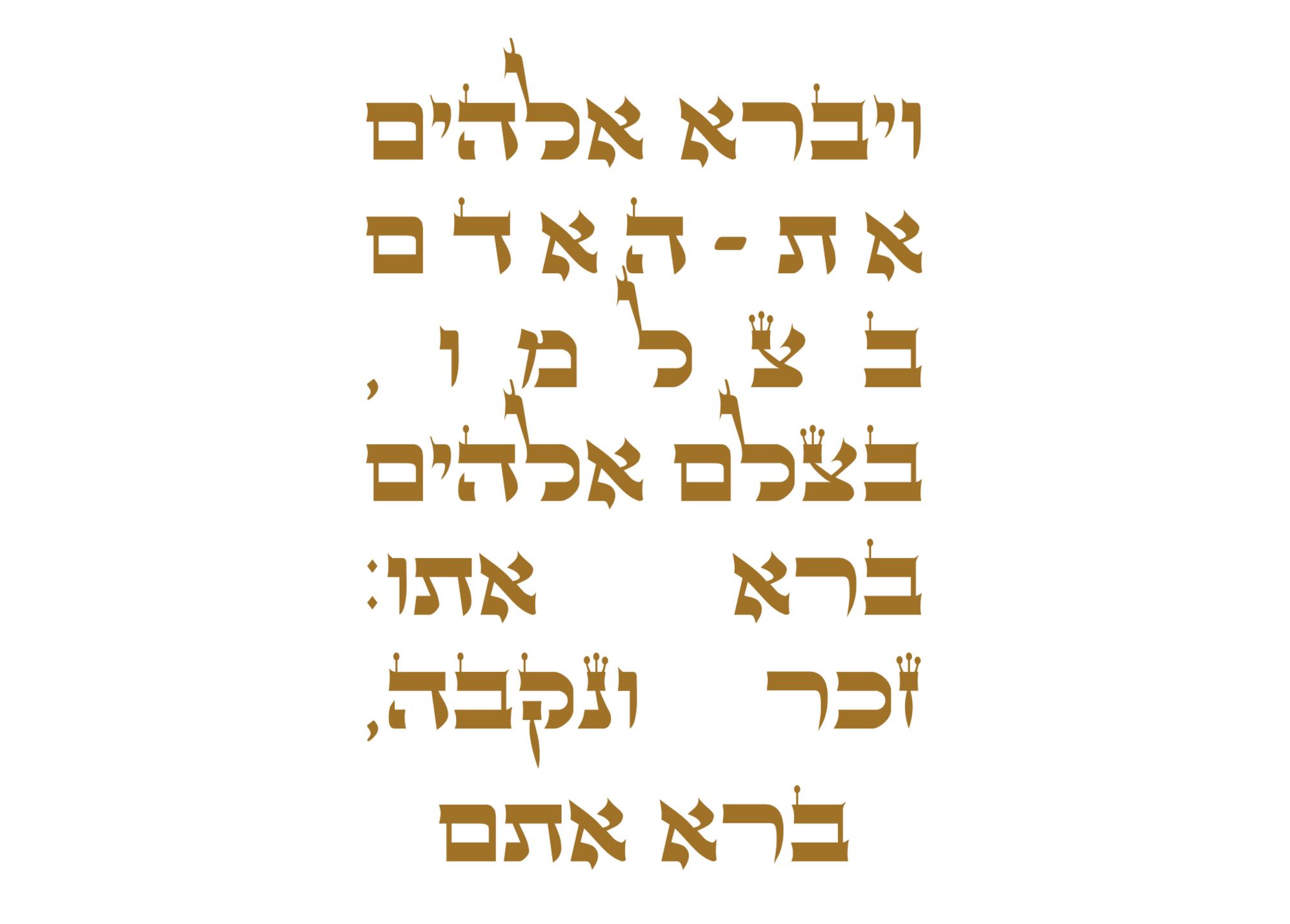

Over the period of Late Antiquity, the Babylonian Talmud was written in Babylonia, the most important Jewish center of Mesopotamia (contemporary Iraq). This rabbinic text comprises of Mishna (the Oral Torah) and Gemara (its scholarly interpretation), and it outlines six gender categories—zachar, n’keva, androginus, saris, aylonis, and tumtum. Zachar is male. N’keva is female. Tumtum is when a person’s sexual characteristics are indeterminate or obscured; whereas aylonis is someone who is identified as female at birth, but develops male characteristics at puberty and is infertile. Saris is someone identified as male at birth, but who develops female characteristics at puberty or is lacking male genitalia. And androginus is to have both male and female sexual characteristics, like Adam. According to Genesis: “God created man in God’s own image, in the image of God, God created him; male and female, God created them.”

Maya Ober (she/her) is Basel-based activist, educator, designer, and researcher, working across different mediation formats. Together with Anja Neidhardt, she co-runs depatriarchise design, a non-profit design research platform. Maya works as a research associate and lecturer at the Academy of Art and Design in Basel and researches intersectional feminist pedagogies of design.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.