“Norm criticality involves the highlighting of power,” states the website of Norm-Creative Master Program in Visual Communication at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, Sweden. I immediately identify with this sentence: it’s August 2017, and I’ve just launched depatriarchise design—back then, a blog born out of the urgency to scrutinize design’s entanglements with systems of oppression. My call for action quickly resonates with others—amongst them Benedetta Crippa, one of fifteen Swedish and international students to graduate from the two-year program focusing on developing “norm-creative practices” in graphic design and illustration. Crippa reaches out via Instagram and suggests a Skype call with Johanna Lewengard, the Professor of Graphic Design who in 2013 co-started the program with the Professor of Illustrator Joanna Rubin Dranger. Hopeful and longing for alternatives in design, I am thirsty to learn from others who believe that the ultimate duty of art and design schools is, as Lewengard later tells me: “to create conditions for new knowledge to emerge with possibilities to change paradigms.”

My experiences of design education are quite the opposite. Design history, as I’ve learnt, is the story of genius individuals—predominantly, white men—who, “driven by their determination,” managed to reach the highest positions in the discipline. Power structures underpinning design and its political and social contexts were rarely discussed—instead, we were presented with a neutral and apolitical vision of design, defined by so-called “objective” and unalterable norms. As an undergrad, I never analyzed design’s entanglements with systems of oppression such as racism, patriarchy, colonialism, ableism and others. Is a paradigm shift possible, I wonder? On a sunny afternoon, I curiously joined the video-conference with Johanna and Benedetta to learn about a design program challenging dominant norms and upending the status quo.

Many lively Skype sessions and Google Docs discussions later, in January 2019, we published the resulting conversation on the website of depatriarchise design. A lot has happened since. In November 2020, Johanna, together with Sara Teleman, a professor in illustration and program’s current co-head, welcomed Sweden’s first doctoral candidates in visual communication. Today, as Johanna’s ten-year term as co-head of the program comes to an end, we bring to you an edited and updated version of this conversation to honor her legacy in opening paths to liberatory design education. In this conversation, we talk about how different aspects of power intersect in design, how “norm-criticality” can be used as a lens, and the importance of safety in education.

Maya Ober: Your program’s declaration really speaks to me. What is it about?

Johanna Lewengard: Basically, it is about acknowledging that communication does not exist in isolation—it is always situated within a socio-political context, and responds to the reader, user or community it is supposed to serve. For the Norm-Creative Master’s degree, we make past and present apparatus of discourse visible; and give space for students to navigate and expand their own practices more consciously. Our program is a process of co-learning where we—teachers and students together—elaborate upon existing knowledge while recognizing our individual (and thus different) experiences and approaches to practice.

We are all part of a society being formed and defined by a dominant few, and the program started by simply acknowledging this unequal order as a fact. And, if we are about to seriously explore how power structures articulate themselves through what we do and how we do it, then feminist and postcolonial methods and theories are very useful—if not necessary—tools along the way!

“We are all part of a society being formed and defined by a dominant few, and the program started by simply acknowledging this unequal order as a fact.”—Johanna Lewengard

I find it interesting that you can easily identify with our declaration about the highlighting of power, since this is exactly what bothers some people! Every now and then we discuss whether it is wise for us to use this terminology, and the answer is always yes. Our outspoken approach engages a lot of people who could not find equivalent education elsewhere. Each year, we have applicants from over 30 countries around the world—people who are already trained in visual communication, but wish to expand their practices while finding out what truly makes sense to them personally.

Maya: How do you deal with these critical reactions?

Johanna: We are constantly learning. Most of us teaching at the program have been engaging with feminism and anti-racism for many years. We are used to the fact that we have to be more thorough than most, and that if you work with these questions, in public the margin for mistakes simply does not exist. We were aware of this when we started the program—we knew we had to be technically flawless to avoid backlash. However, most reactions are not outspoken; rather, they are shown through attempts to silence us. I think we have grown a pragmatic approach to this: we cannot deal with what is not at the table since this would take too much energy that should go to our core activity: education.

Benedetta Crippa: When I applied in 2015, I understood the program as being concerned with adding a layer of new knowledge and awareness to the practice. Even if you retained the exact same skills you already had, you would gain a renewed sense of their impact—on a personal and also on a systemic level. I would say the program is not simply skills-based but also conscience-based, which is very rare in visual communication and design education in general.

Maya: Academia can be a very rigid structure, with lots of internal politics, and sets of priorities dictated by those in power. The program you created questions the very foundations of what we know as design education. How did you do it?

Johanna: As a graphic designer, every day I navigate existing conditions. This knowledge allows me to approach challenges at the academy as a design task. But an even more important factor that made it possible to rethink, plan, and implement the new program in such a short time between 2013 and 2014 was the people who were already there.

When I arrived at Konstfack in 2012, I met Joanna Rubin Dranger, who was the Professor of Illustration until August 2017. She and I shared some basic values and visions on education, and this synergy proved essential. The two of us could very naturally start imagining alternative futures of education, without explaining the fundamentals to each other! On top of this, Maria Lantz, who was then the newly appointed Vice Chancellor, held a very sensitive approach to leadership. She makes space for collegial dialogues to guide the university forward, which has allowed for multiple views and voices to co-exist.

I should also mention the social scientist and feminist scholar Rebecca Vinthagen, who together with Lina Zavalia coined the term “norm-criticality” and has been part of our conversations since the very beginning. Rebecca’s work to foster a non-violent space in which the students can elaborate upon both sensitive and complex questions is crucial to the studies ahead. And then of course, there’s the contribution of Parasto Backman and Emma Rendel, both senior lecturers in Graphic Design and Illustration respectively, whose daily work to refine and develop studies is invaluable. Together with Moa Matthis, senior lecturer of History, Theory and Context, they carry out this education with both excellence and great compassion. Overall, we have an educational team at Visual Communication that I could not have dreamed of creating, joined by a love for practice and commitment to push it forward.

Bendetta: But how to create sustainable change? That is, how to mold a structure that is sustainable beyond specific people, or a steady foundation that both students and educators can utilize and build upon?

Johanna: To rewrite a program is neither a quick fix nor a one-person job, and it should not be. It is a task that requires the most solid and transparent processes of articulating, arguing and anchoring. Developing curricula on both the program and course level is a work of negotiating and balancing what can and cannot happen. The space for interpretation has to exist to inspire actions beyond the minds of the authors, while it has to be clear enough to inform a minimum standard.

Benedetta: Which kind of gap do you think the program fills in the field of visual communication?

Johanna: This becomes obvious each year during the admissions process and when we meet with new students. Since the program operates at a Master’s level, some of our students have already had years of practice, and their expectations are the most valuable measurement. They expect to find teachers who will not just focus on what men do, but an expanded and more diverse library of references. They expect transparency of teaching methods and forms of critique, and to feel emotionally and socially safe, and so on. This is not only telling of what the program became recognized for, but also of how things that should be obvious are still not there.

“Giving ourselves methods and tools to investigate the colonial, imperial, and patriarchal gaze is a practice of freedom, since it can liberate us from what we perceive to be ‘normal’ in our daily lives.”—Johanna Lewengard

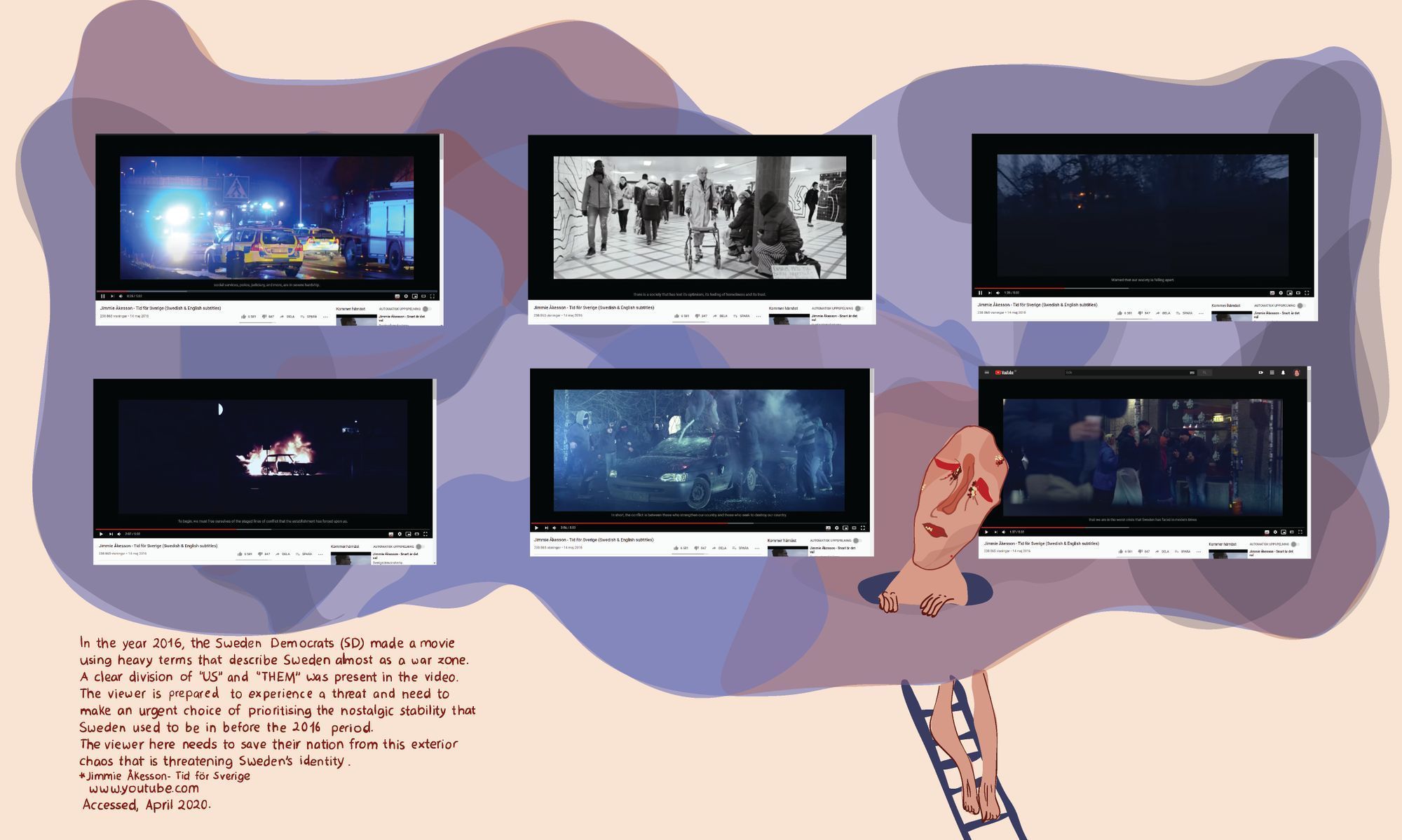

On a macro level, we fill a gap in acknowledging education as a critical practice, situating visual communication within a broader social, cultural and economic system, and navigate its power imbalances. As with popular culture, visual communication plays a crucial role in how ideas on reality are shaped—ideas on how we look at each other, and ourselves. Most of us would say that we are not racist, sexist, homophobic or transphobic, yet we are surrounded by a visual landscape reproducing and reflecting these systems of oppression. Giving ourselves methods and tools to investigate the colonial, imperial, and patriarchal gaze is a practice of freedom, since it can liberate us from what we perceive to be “normal” in our daily lives, without always knowing the reason behind it. But it is also a way forward in making more conscious design decisions.

Benedetta: I have always felt that as designers we are deeply accountable, but this is not the message that is usually passed on through design education. Actually, it’s quite the opposite: the dominant rhetoric tells us that we are not responsible for the choices of our clients, our customers, our suppliers, or even our own; that as service providers we bear no liability. Accountability is not only a topic discussed in the program, but brought to the very centre of education. Finding this space was a relief for me—it was like a place that I wish existed, but had never encountered before.

Maya: You started in 2013 with a pilot programme that lasted for five weeks, which you described as a very intense experience. How did you reflect upon it afterwards, and how did the conclusions from this pilot help you develop the current program?

Johanna: We realized the importance of time and space for reflection, and we realized the importance of staying close to the process of making at all times. When unpacking questions of power, it is easy going into existential questions, realizing that freedom is in many aspects an illusion. From people teaching Gender Studies, we learned that this has certainly had an emotional impact, but also that there is not really a way to avoid this rather painful learning experience. As an educator, I can at least be aware that it is going to happen, and stay mindful about it. Since every student is different, each one will be affected in a different way.

Maya: How is the course structured?

Benedetta: It starts with a four-month full-time introductory course where we discuss visual communication in relation to systems of oppression—patriarchy, racism, and colonialism are the main topics. Lectures mostly take place in this first semester, and in the following year and a half, students formulate their degree work under the guidance of internal and external tutors. Beyond this basic structure, each student decides for themselves. People have different ways of shaping their educational experience, which affects the collective outcome and makes it different year by year.

There are only a few “bibliography” of texts we use; instead, the exchange of knowledge happens mostly in person through discussions, presentations and feedback sessions. As a whole, the program is primarily based on dialogue and presence. Feedback sessions follow non-violent, feminist approaches. The class sits around a table, and one by one we share our progress with others in the room. Everybody—teachers and students—gives their feedback, and then a discussion ensues. In general, the kind of feedback we get is primarily concerned with the craft through “norm-critical” and “norm-creative” perspectives—that is, the practice of identifying and proposing responses to existing norms. At the end of the program, as in other design schools, we present our work in a final exhibition. The final examination takes place in that exhibition, and it is conducted as our regular feedback sessions. In addition, an external person is invited to partake in the dialogue with us.

Maya: What kind of norms and power relations in visual communication could you address within a feminist context?

Johanna: Oppression against women, to focus on one category, is perpetuated through a single-layered and repeated narrative on femininity. Understanding power relations from a feminist perspective requires challenging ideas such as women being a homogenous group. We chose to label the program as “norm creative,” partly since it responds to social challenges that are factual and well-grounded, and partly since it employs methods that are transformative. Norm creativity allows for a focus on how various aspects of power intersect—which is why, for example, we don’t specifically label it as “feminist” or anything else.

“To go beyond ‘good intentions,’ it is crucial to recognize that injustice is not just maintained because some people don’t believe in equal rights, but because we didn’t fully explore how this equality should translate into practice.”—Johanna Lewengard

It is crucial to recognize how norms are enforced through a neverending series of subtle and often well-intentioned actions. In fact, one of our most important learnings is distinguishing intention from outcome. To go beyond “good intentions,” it is crucial to recognize that injustice is not just maintained because some people don’t believe in equal rights, but because we didn’t fully explore how this equality should translate into practice. Having said that, we don’t expect students to embark upon over twenty years of feminist studies! The program is practice-based, and we are careful to avoid getting stuck in theory. Our students become specialized in holistic making, rather than in specific theories.

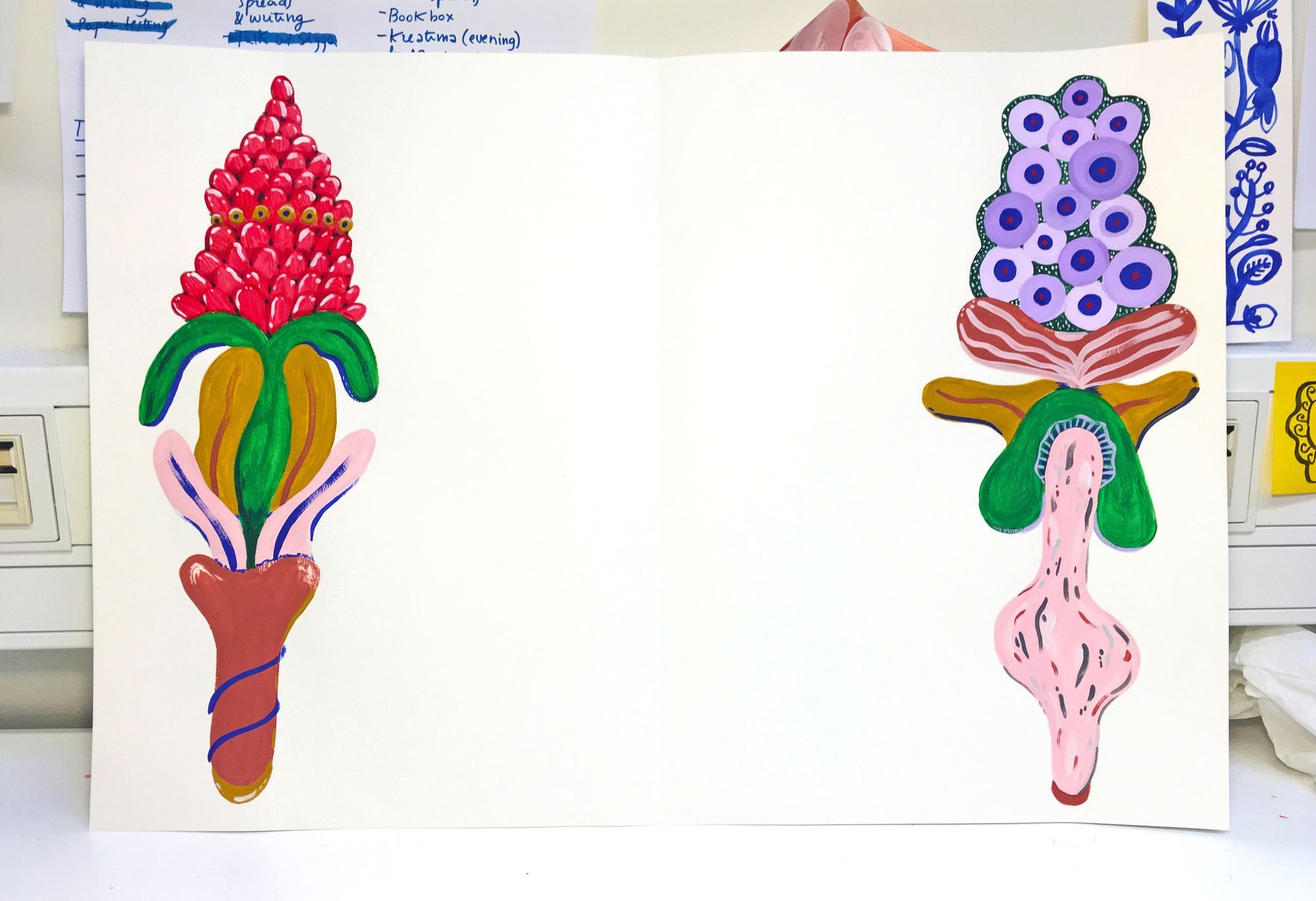

Maya: Benedetta, your degree project explores drawing and decoration as historically marginalized crafts within the field of visual communication. How did the contents and the approach during the introductory course influence your work?

Benedetta: The first months were important to situate myself, and in a way become visible to myself. I went through a phase of realization and recollection of unspoken wounds and profound needs and longings that I had kept within up to that moment. This allowed the most intuitive, and internalized processes to emerge, be exposed, re-interpreted and finally addressed. It is crucial that this happened through practice, as it allowed for the growth of both myself and my practice as a designer.

Coming from a deeply patriarchal culture like Italy, the program was an ongoing discovery that there was space for me, after all—something I never felt during my previous education at the Politecnico of Milan, and the Iuav University of Venice. As other students, I had experienced design education where harsh and violent modes of critique were commonplace, the relationships with educators were highly hierarchical, and I often felt invisible as an individual. The main narrative within design education is that we are not supposed to bring our own selves or our own history, or any sense of accountability into the work. At Konstfack, however, I felt visible—that my experiences and values as a woman and as a human being were visible, and that I had the space to bring them into my work. That is a powerful experience.

Johanna: The idea of a master-apprentice relation underpins traditional ways of giving critique within design education, a scenario generated by a limiting view of how knowledge comes into being. According to this tradition, knowledge is a linear transaction, i.e. “I choose to give my knowledge to you, and then you will be at the same level as me.” This approach to critique never contemplates knowledge as something we co-create, i.e. “You bring your perspective, I bring mine, and by sharing it we start growing knowledge together; knowledge that would not have existed if we had not entered that room together.” We must abolish this single idea of knowledge as a linear transaction, because this speaks only of how we transfer knowledge, rather than how we expand it. “Teach what you need to learn” was a pedagogical motto for us when we planned for the program. It encourages us to bring to class questions of high importance to visual communication—questions that we do not yet have the answers to ourselves.

“We must abolish this single idea of knowledge as a linear transaction, because this speaks only of how we transfer knowledge, rather than how we expand it.”—Johanna Lewengard

Maya: My experiences as a student were similar to Benedetta’s. Even though my school encouraged students to critique one another's work; in the end, it seemed like you were only worth what your work was deemed to be worth, according to some professor. Additionally, in design, those star designers on top have their sole names behind a project, even though there’s often a whole team that worked on it. This lack of acknowledgement of collaboration, recognition, and co-creation of knowledge only reinforces the structures where individualism is promoted. The alternative you propose abolishes the familiar mechanism of our very existence and practice as designers.

Johanna: Education is never a neutral process. It either functions as an instrument to integrate new generations into the logic of a present system, or it can be the means by which students are allowed to critically deal with their reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their future—in other words, education as a practice of liberation. No matter what we believe, we all should at least be transparent about our approaches. Every student should have the right to know what kind of learning processes they are about to enter.

And of course, one is more likely to support education as a model of integration if one benefits from or has never felt threatened by the status quo. In this case, this system is likely invisible to you. In liberatory educational practices, it is as important to recognize one’s role as an educator as it is to identify and name power. This should never be confused with freeing yourself, as a teacher, from your responsibilities. Even if I believe in co-created knowledge and use methods to make individual experiences and knowledge visible, it is my responsibility to organize studies in ways that increase each student’s chances to reach learning outcomes. If a student fails, this failure is also mine.

Maya: Benedetta, what were the most significant learning outcomes from the course?

Benedetta: The lesson that feeling safe is necessary. Feeling safe does not mean to reject the notion of taking risks, but rather to recognize what one needs in order to express her full potential, and actively look for, welcome and create the conditions to facilitate this. With safety, I do not mean that the environment should be unchallenging—I am talking about that kind of basic safety that makes it possible for us to grow and be challenged.

In that, two crucial elements are practical stability and emotional safety. The Norm-Creative MA gives students a lot of time and a physical space to work, and in addition to that, the school is always accessible. This creates a safe base for students they can depart from and go back to. From here, we can see the importance of advocating for free public education for all that grants students a monthly allowance, thus ensuring economic stability. At the moment, in Sweden, education is tuition-free for EU/EES citizens only; for students outside the EU/EEA, the MA comes with a hefty price of over €52,000.

“Feeling safe does not mean to reject the notion of taking risks, but rather to recognize what one needs in order to express her full potential, and actively look for, welcome and create the conditions to facilitate this.”—Benedetta Crippa

Emotional safety, on the other hand, means knowing that I am trusted with my work; that I am not threatened or questioned as a person; that I am here because I can learn as well as give; that my lived experience is neither invisible or dismissed, but recognised and valued. Other students are not my competitors, rather they are people whom I can learn from and grow with, who can support my work with their presence, advice and expertise. The positive impact my classmates had on my project still resonates with me. Although it is not the only factor, I believe the institution plays an essential role when it comes to encouraging this kind of environment.

What I am mostly bringing into my professional life is the conscious decision to work and be in dialogue with people who are interested in an honest conversation of growth and non-violent practice. I am referring to colleagues, but also to clients. Being selective is important—it does not mean that you create a bubble around yourself, but that you establish the conditions you need in order to create work and that leads to change.

Maya: During my undergrad design education, I had a feeling that everything was planned in a way so the students, instead of supporting each other, would compete. In retrospect, I understand that all the competitiveness that we were fed with and the concept of “uniqueness” and “ingenuity” created a real fear that inhibited us from co-creation and co-exchange. At the same time, there was no acceptance for mistakes: often, when I was not satisfied with the development of a project, with my models or sketches, I would skip a class because I felt that it was not good enough and I was too terrified to show it.

Benedetta: That is why I feel that it is important to go beyond the notion that you are only worth what your work is, as that can hinder or even paralyze the creative process. It is so crucial to be able to experiment, while knowing that this will not affect your worth as a person! This is very rare not only in education, but in society at large, considering that capitalism pushes us to identify people’s worth with the work they do.

Maya: Johanna, what were your experiences as a design student, and how did that inform the program?

Johanna: I share both of your experiences of entering a competition rather than a collegium. I believe my teachers thought of this as a way to prepare us for “reality,” ignoring the fact that we would face a lot of realities where collaboration and empowerment would be equally or even more important. I will not spell out all the ways in which my teachers would punish and shame students, but at the time we did not see it that way. We accepted violent teaching as something that comes with being challenged, when in fact it was about being destabilized. Maybe this is one of the most important things for us to distinguish: “challenging” in the context of an education environment must never be about making it emotionally and socially tough for students. What Benedetta says about emotional safety and practical stability is truly important. I believe we are not fully ready to be creatively or intellectually challenged unless we are in a safe place. This idea of competition as the main tool for progress is one of the most sinister narratives of time.

Maya: How do you think such normative practices and narratives have been historically constructed?

Johanna: I studied typography in the late 90s, and one of my teachers baffled me by saying that women cannot be skilled typographers. When I asked him why, he answered that I should inform myself about the history of typography to find that there are no (or very few) women. His way of navigating this issue is what philosopher Elizabeth Kamarck Minnich would label as circular reasoning—one of the basic errors that work to uphold and reproduce dominant traditions. Circular reasoning creates the conditions for certain status of things, then uses it as evidence of itself. But what we need to see is that this teacher was neither far from alone nor acted from bad will: any tradition that builds upon standards articulated by a dominant few allows for a system of thinking that is more or less shuttered. And we are all part of its constitution, unless we actively learn how to recognize and work beyond its mechanisms. I believe that unpacking dominant ways in which the writing of design history becomes dogmatic is a way to liberate and expand practice.

Benedetta: My first encounter with graphic design history was during my Bachelor’s degree studies. I remember listening to the lectures, browsing through the books and realising how design history was a celebration of the genius of a series of individuals, almost exclusively men, mostly disconnected from their context. I could not see any connection between how design history was presented to me and the world I lived in. It was troubling to observe design history being grounded in a narrow perspective that ignores the role of design as a cultural practice, deeply embodied as it is with the society it is produced in, and inevitably intertwined with its context and its systems of power.

From history books, one learns nothing about how design actually comes into being and how it operates in the world. There is a complete, embarrassing lack of socio-political contextualization whatsoever, as well as a rigorous analysis of the modes of production of design and their impact(s). We must ask ourselves why we have built a history that serves itself (and certain groups of people) instead of us collectively, and how this reflects a patriarchal view of reality.

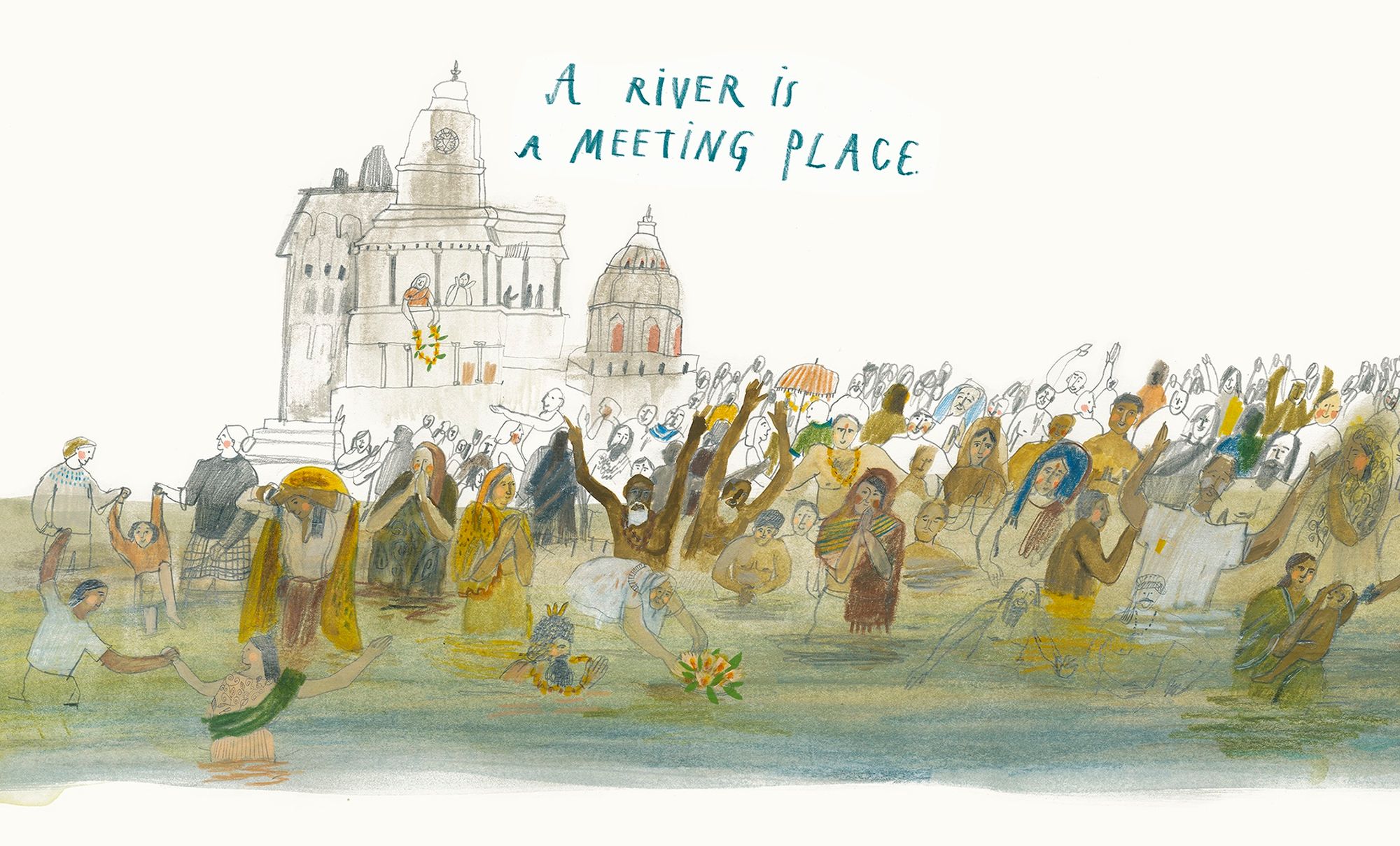

What I long for today is a history of graphic design and visual communication that focuses on visual culture rather than production of artefacts by individuals, and that operates from a place of awareness of graphic design as a cultural force. Even more rare, one that also situates the Western context within a more global visual culture, able to read the developments of visual communication in a broader landscape through the celebration of a plurality of visual cultures and languages. I am still waiting for such a book to be written.

Johanna: Maybe you should write that book, Benedetta!

For a complete archive of projects from the program illustrating the interview, see the year 2016, 2017 and 2018. By searching with the name of a student, you can also read project reports on the DIVA portal. The project reports recount the process behind the degree works from beginning to end.

Maya Ober (she/her) is an activist, educator, designer, and researcher, working across different mediation formats. She is Futuress's co-director and founder of depatriarchise design. Maya works as a doctoral researcher at the Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Bern and researches feminist practices of design.

Johanna Lewengard (she/her) is a communication designer and educator based in Stockholm. She has been working for over 20 years with projects across art, culture and business that aim to transform meaning and value through visual communication. Her ongoing research is dedicated to explore dimensions of inclusion and exclusion through communication processes, and how this comes down to the very craft of graphic design.

Benedetta Crippa’s (she/her) practice is a focused investigation on how graphic design can expand beyond current boundaries of methodology and aesthetics. Her background and visual research in Italy, Nepal and Central Asia have shaped her distinctive visual language, where she uses ornamentation and experimental investigations to revisit ideas around beauty, form and power.

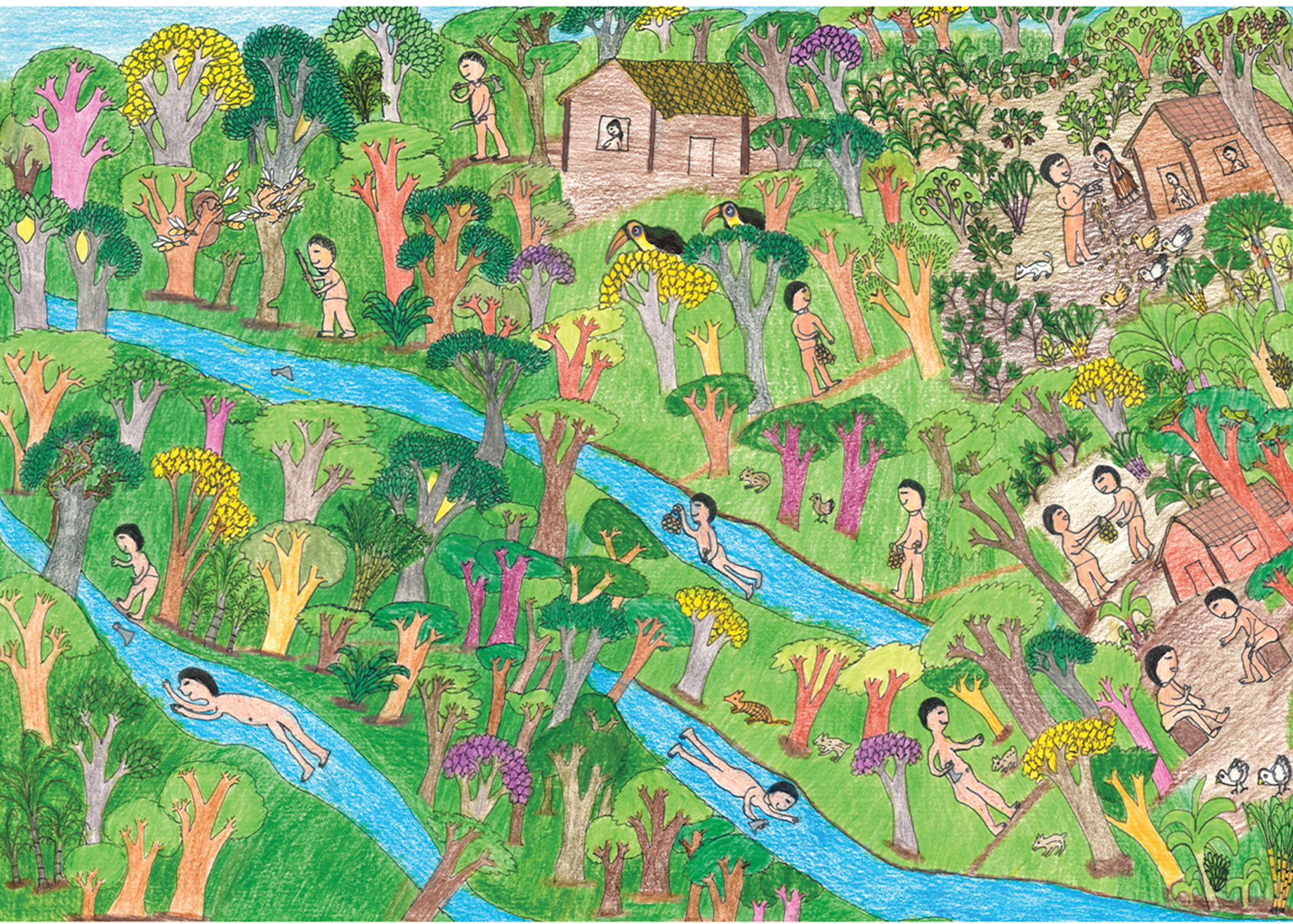

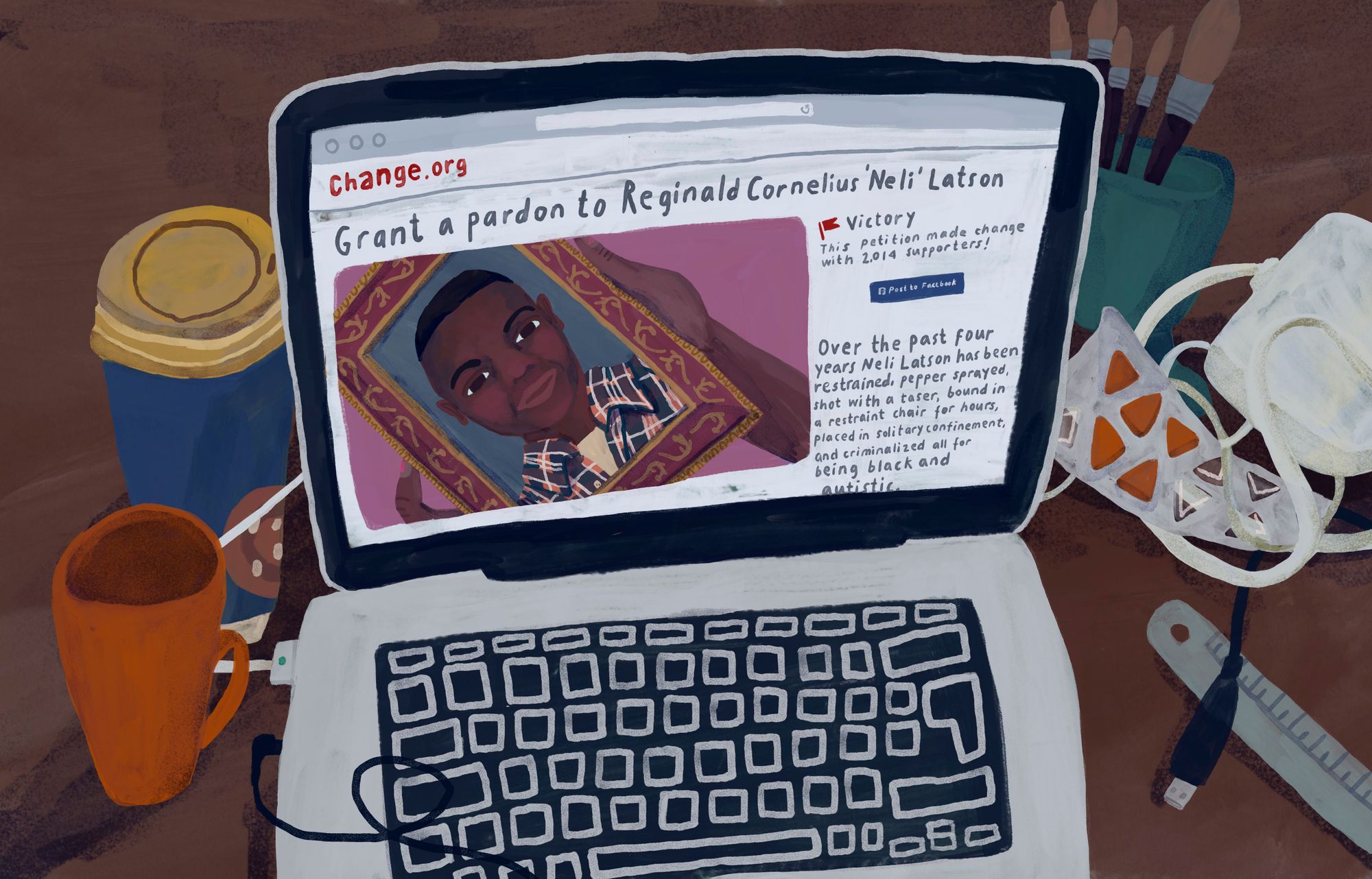

Title image: Collage with details from final projects by MA students. Used works include: Altar of Friendship by Aziza Ahmad, World of Desire by Benedetta Crippa, Refugees Welcome? by Hayfaa Chalabi, Market Values by Brit Pavelson, Filling in Physical Reality, Living in Digital Reality by Gyonyoung Yoon, My Autistic Practice by Nathalie Ruejas Jonson, What is a river? by Monika Vaicenavičienė.