The square in front of Argentina’s Congressional Palace symbolizes battle, hope, and hard-won rights. From the first #NiUnaMenos demonstration against femicides and gender violence in 2015 to the #SeráLey march for the right to abortion in 2020, the Plaza del Congreso has witnessed the largest feminist mobilizations of the past decade. It’s Friday, October 7, 2022 6 p.m., and I am here to attend the 35th Encuentro Plurinacional de Mujeres, Lesbianas, Trans, Travestis, Intersexuales, Bisexuales y No Binaries (The Plurinational Meeting of Women, Lesbians, Trans, Intersex, Bisexual, and Non-Binary people) in the province of San Luis, the territory of the Huarpe, Comechingón, and Ranquel Indigenous communities. The Encuentro is a three-day annual event that brings together thousands of people from across the country to meet and discuss pressing feminist issues and define the future political struggles of feminist movement—the amalgam of diverse intersections rather than a singular whole: indefinite, ever-changing, and always in motion. I join the collective excitement filling the square: students from Buenos Aires’ public universities, activists from popular neighborhoods, political movements, and unions meet after two years of pandemic pause. Following decades of internal conflict and struggle, for the first time, the Encuentro’s name explicitly recognizes and celebrates the many identities and Indigenous nations that make up Argentina’s feminist movement.

I meet up with Giuliana Bonifacio Alvariza and Emilia Odriozola from AUGE (youth on rise), which identifies as a feminist, inclusive, and sustainable student movement at the Faculty of Architecture, Design, and Urbanism (FADU) at the University of Buenos Aires. I have been involved with AUGE’s activities as part of my ethnographic research for several months. Today, we sit in a circle on the pavement, chatting, playing cards, and drinking mate as we wait for people from other faculties to join us on our 11-hour-long bus trip to San Luis. The sun sets behind the Plaza del Congreso, and several activists make numerous phone calls as they stroll around us, gesticulating nervously. Three of the eight buses organized by Somos Barrios de Pie, a left-wing social movement and an umbrella organization of AUGE, are not yet here. Neither the transportation company nor the drivers are answering their phones. “Probably, someone offered them more money. It’s a long weekend, and the demand is high,” Giuliana speculates, voicing the fear shared by many. With the current inflation rate of 80%, the downpayment for the bus has already completely devalued. Fellow activists report that bus companies scammed various feminist organizations and never showed up.

As the desperation at the square increases, I receive text messages from my partner telling me that our daughter’s fever hasn’t subsided. Mixed feelings crush my spirit. I am torn between care duties, feminist activism and research. It’s been five hours. Will we ever depart? At last, Giuliana announces that they found one bus. The organizers prioritize those participating in the Encuentro for the first time. Along with other newbies, I embark on an overnight journey. It will be many hours before I rejoin my compañeras (comrades), the affectionate term we’ve been using for each other, which makes me feel attached to Argentina, where I’ve lived for ten months.

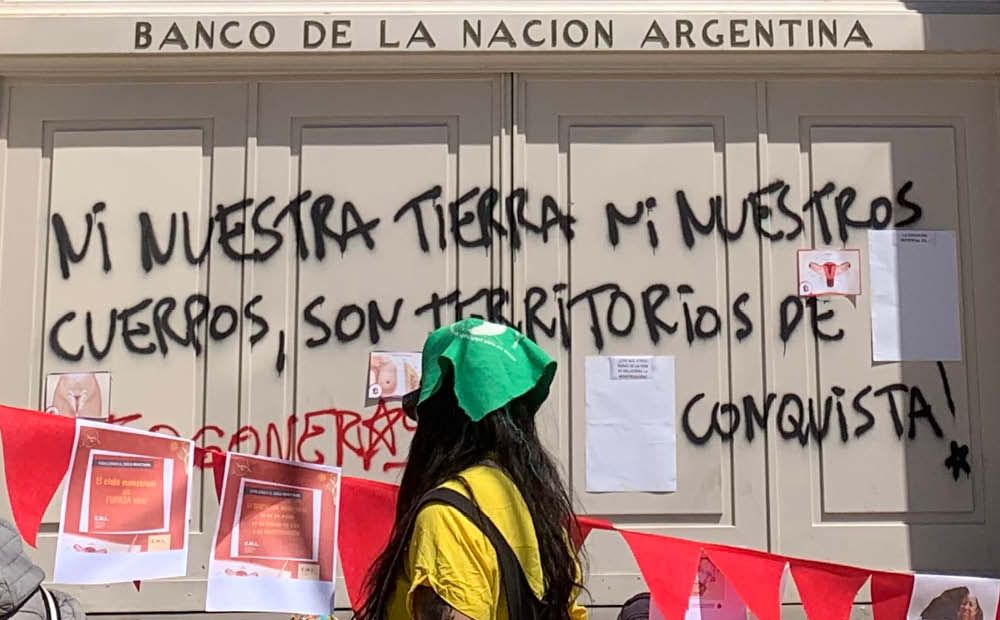

“For decades, Mapuche people have been fighting for the rights to their territory, which was grabbed by the state to serve capitalist and nationalist interests.”

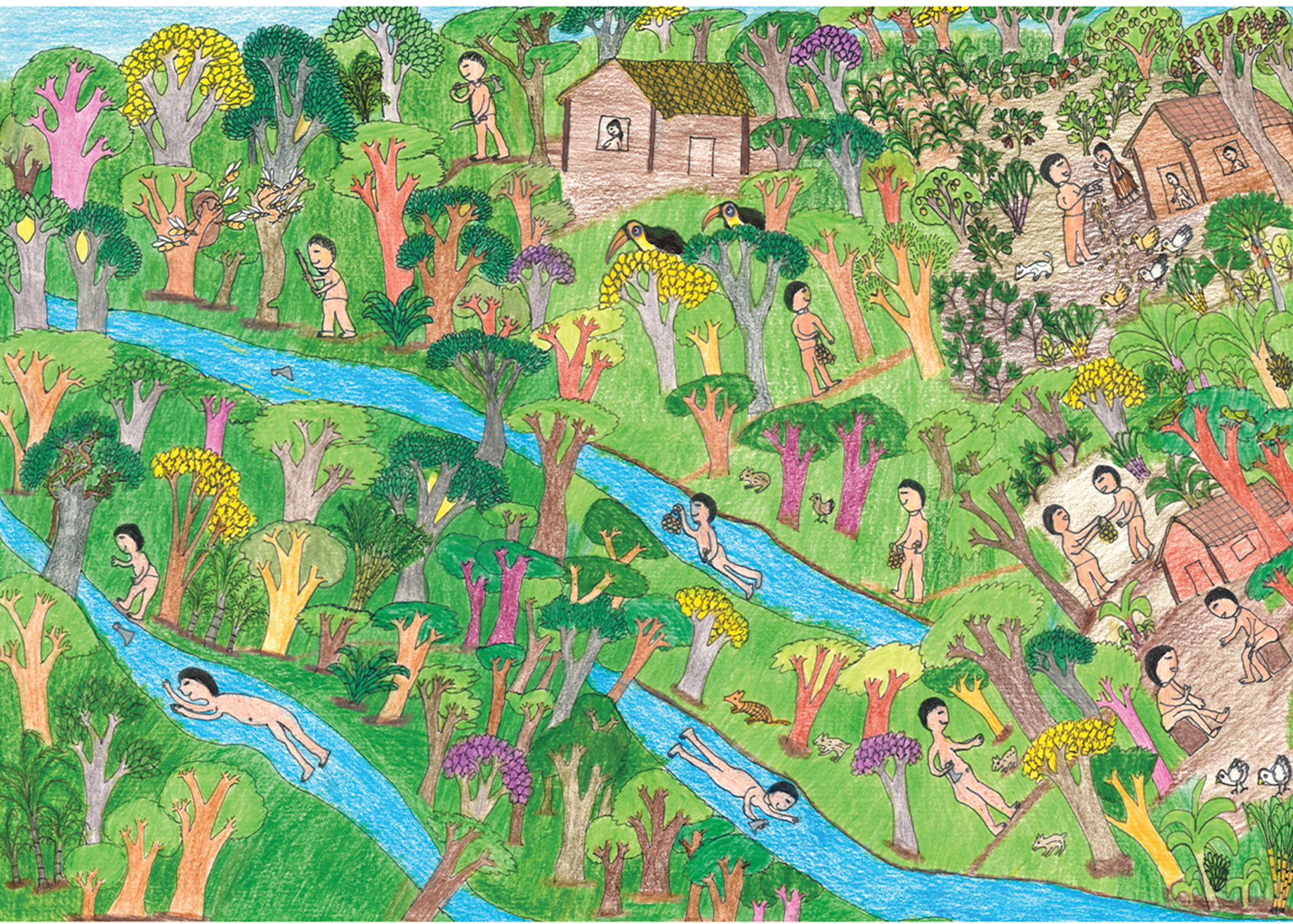

Notifications on my phone wake me up. It’s 9 a.m. and there are still two hours until we reach our destination, but the opening ceremony has already begun at Cerámica Park. There, thousands of people sit in a circle around a bonfire lit by Huarpe and Ranquel women. The crowd waves multiple wenufoye, the Mapuche flag and colorful wiphalas, the emblem representing the Indigenous peoples of the Andean region. During the opening ceremony, the Organizing Committee clearly defines the politics of the meeting: they demand the immediate release of seven Mapuche women who were arbitrarily arrested just a few days earlier during a brutal eviction operation by the police to the Lafken Winkul Mapu Community in Villa Mascardi, Rio Negro Province. For decades, Mapuche people have been fighting for the rights to their territory, which was grabbed by the state to serve capitalist and nationalist interests. Despite the ongoing colonial violence, the opening ceremony ends with a strong prevalence affirmation in Mapuzungun, “Marichi wew,” meaning “ten times the victory.”

What is not named does not exist

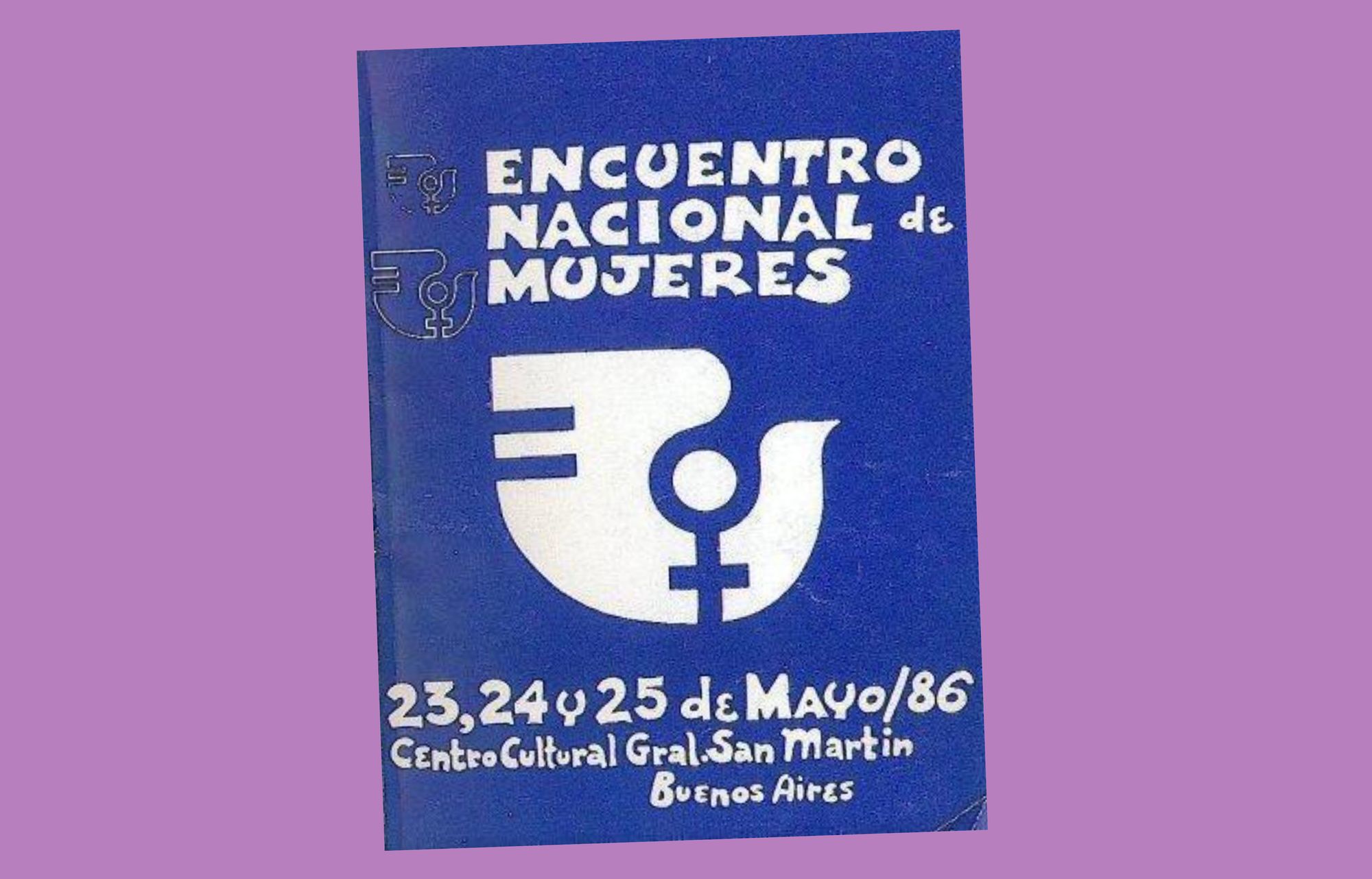

Anxious about restoring democracy and eager to bring change following Argentina’s last sinister military dictatorship (1976-1983), in 1985 several local feminist activists participated in the third Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericano y del Caribe (Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Meeting) in Brazil and the third International Women’s Conference in Kenya. These events inspired them to initiate similar practices in their country where, at the time, divorce and abortion were forbidden, and the president was required to be of Roman Catholic faith. The first meeting, called Encuentro Nacional de Mujeres (National Women’s Meeting), took place in Buenos Aires in 1986, and gathered about one thousand participants. Since then, the Encuentros have been free to attend, and are financed through participants’ donations. Each year they take place in a different city, and the organizing committee in the venue’s location is made up of hosting locals and activists from across the country. They are responsible for budgeting, communication, and defining the program of the talleres (workshops)—the main activity of the event—which can be extended by proposals from participants in the form of self-convened workshops.

Since its inception, cis-white activists and academics have dominated the Encuentro's organization, determining its name and setting its agenda. The one-dimensional depiction of “women”' in the original name reinforces an essentialist idea of womanhood. Defined by biological determinism, it homogenizes the many gender identities under binary logic. At the same time, the concept of “national” as an umbrella term excludes the plurality of cultures and identities that participate in the meetings. By not having workshop spaces organized by and for them, many collectives were excluded from participating and defining the politics of Encuentros. After years of ostracism, Indigenous women highlighted their struggles and self-convened their first workshop, “The colonization of the body 500 years after the conquest of America” in the 7th meeting in Neuquen in 1992. During that Encuentro, around five thousand participants marched to condemn the genocide of the Indigenous peoples the Argentine state had committed since 1810, the year of the nation-state’s so-called independence.

“The myth and ideology of ‘Argentina Blanca’ (White Argentina) [...] led to genocidal policies systematically erasing populations of Indigenous people and those of African descent.”

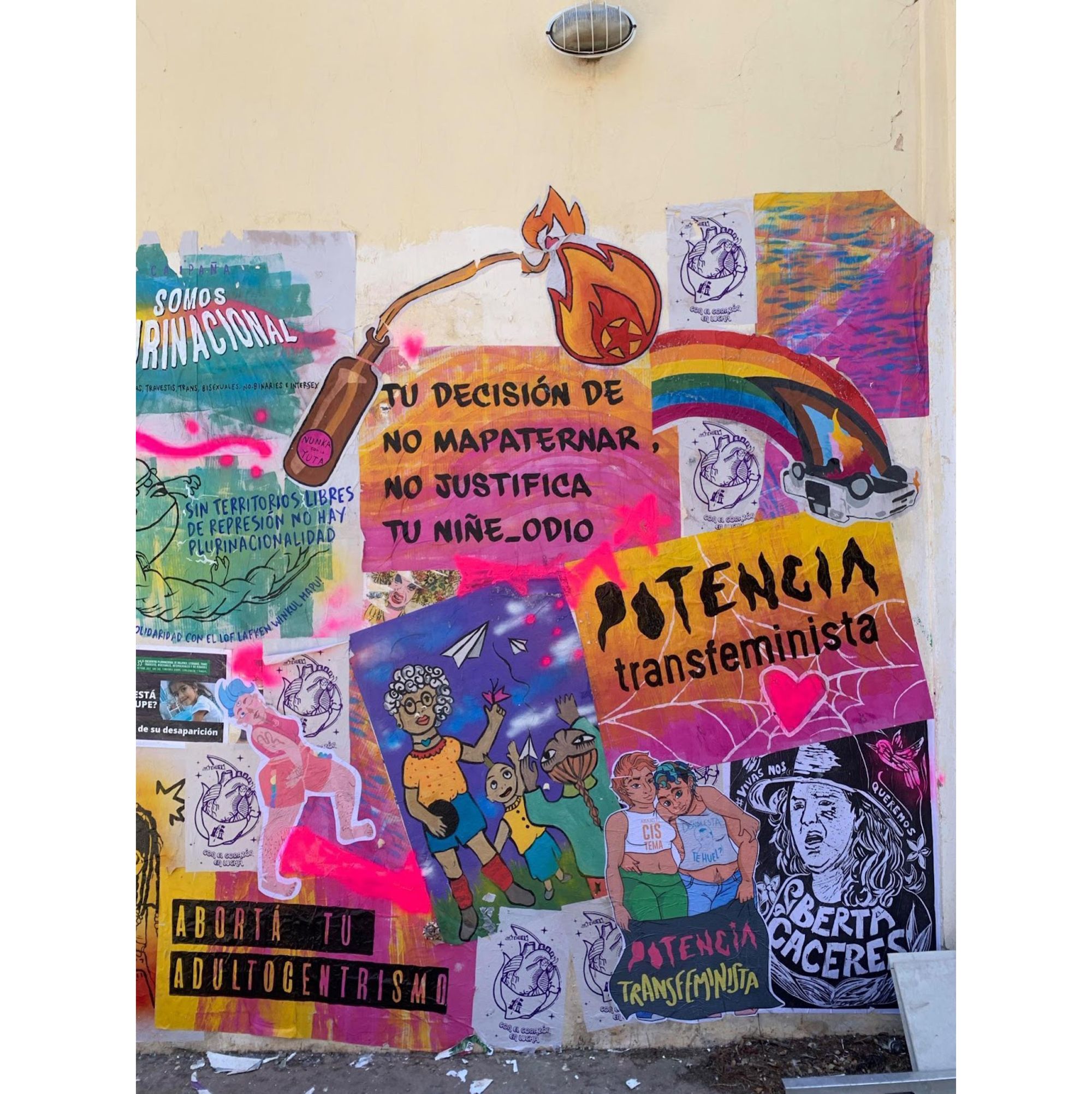

Other marginalized groups followed the Indigenous demands for inclusion. Even though present from the beginning, the Travesti-Trans community was neither mentioned nor allowed to participate, as they didn’t fit into the universal category of “woman.” Lesbians demanded recognition and spaces to discuss the experiences of heteropatriarchy. Those of African descent insisted on acknowledging the intersecting experiences of racism and sexism. Finally, after decades of shared demands, Black and Brown people, lesbians, trans, travestis, intersex, and non-binary people came together under the Somos Plurinacional (We are plurinational) campaign and took over the closing march of the 2019 Encuentro held in La Plata. Under the motto “Lo que no se nombra no existe” (“What is not named does not exist”), almost half of that year’s 200,000 participants demanded to explicitly recognize Argentina’s diverse feminist and transfeminist worldviews, cultures, and identities. The name change marks a historic milestone for a nation-state built on the myth and ideology of “Argentina Blanca” (White Argentina) that led to genocidal policies systematically erasing populations of Indigenous people and those of African descent. The process of blanqueamiento (whitening) favored white European immigration and created the narrative of the “crisol de razas” (“a melting pot”) encompassing, among others, Italian, Spanish, Russian, and Polish heritage while denying the heterogeneity of the majority of the population.

Talleres (workshops) as seeds of political struggles

Back in San Luis, the Encuentro’s participants temporarily take over the city, almost doubling its population. They open ephemeral theaters and pop-up cinemas, improvise concert halls, and spread food stalls and art markets offering books, fanzines, art, clothes, and pins across the town. The city is preparing to receive around 120,000 people by organizing camping sites and installing chemical toilets. “Out-of-service” signs cover the banks and ATMs. Some businesses close for the weekend, while others welcome the guests with the Encuentro-friendly sticker on their doors. The police surround churches and state offices with tall black metal walls and install numerous CCTV cameras. The cathedral gets super-maximum protection, encircled by a fortification of metal fences and several police trucks with water cannons. All these “security” measures nurture the popular narrative of “dangerous feminists.” In the past, anti-feminists and the police attacked Encuentro’s participants; now, these temporary spatial arrangements serve as a deterrent, protecting the state institutions. Argentina’s constitution defines the country as Roman Catholic, giving a lot of power to the Church, which causes understandable rage among feminist activists demanding church-state separation—a recurrent hot topic during the workshops.

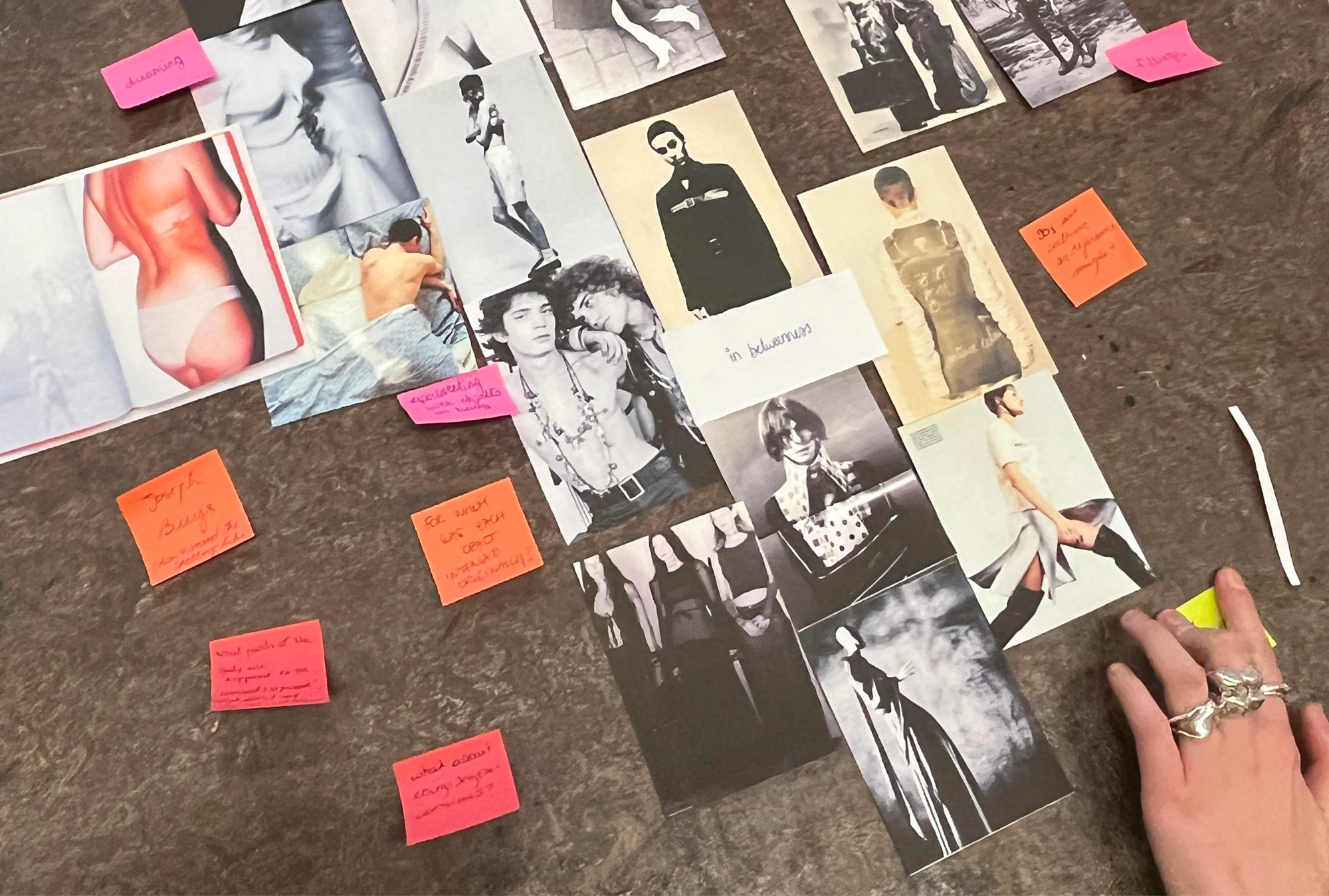

The talleres (workshops) shape the Encuentros. Often called their heart, they form an essential vessel to exchange lived experiences, share struggles, and formulate political demands. To enable fruitful discussions, up to 40 people can participate; if more are interested in a particular topic, new spaces open up on an impromptu basis. Participants take turns to speak, guided by a collectively appointed moderator. In the last session, participants delineate the conclusions for the closing assembly. They lay the framework for the upcoming political agenda and form a historical registry of the feminist movement. This year, over 100 talleres cover topics from lesbianism, sexuality, trans masculinity, Afro (of African descent) and Marrón identities, plurinationality, terracide, and gender-based violence to education, social economy, obstetric violence, fertility, and much more. My head is spinning, trying to go through the list. How can I even choose only one workshop from so many?

“How violent is it that vulva-vulva practices are invisible? The market already conditions our sexual desires.”—a participant of the workshop Preservativos para vulvas (Condoms for vulvas)

The designer in me decides to participate in Preservativos para vulvas (Condoms for vulvas). Since 2019, the homonymous initiative has advocated making lesbian sexuality visible, fighting for love and protection from sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). They collaborate with Cooperativa de Diseño, a design cooperative, on a research project called Gozar (meaning “to enjoy or take pleasure,” and also colloquially: “to have an orgasm”) to develop the first condom for vulvas in the country. “How violent is it that vulva-vulva practices are invisible? The market already conditions our sexual desires,” one person says. Unlike a female condom, which only shields the vagina opening, thus centering heterosexuality, the Gozar condom covers the whole vulva, enabling a range of safe sexual practices such as oral sex, penetration-vagination, and rubbing between genitals. Another participant talks about heteronormative indoctrination: “How come condoms are called condoms, and not condoms for penises?”—thus highlighting the dominant norm defining the design, users, and uses of existing products. Many share how the lack of condoms for vulva-vulva sex and oral sex implies that these sexual practices are not naturalized. A hand beside me rises, and a participant shares: “I am a teacher and a lesbian. It is crucial to say that we enjoy and care for ourselves. The [Gozar] condom makes our sexual practices visible and shows that we shag. It legitimizes pleasure with care.” To our disappointment, the designers don’t show the first latex prototype, as the patent is still pending, and they want to protect it from capitalist interests that might try to take advantage of the endeavor. Despite that, the excitement to test out the condoms fills the room, even if it will take a few more years to reach potential users.

“What do you think will be the next marea verde (green wave)?” many have asked, referring to the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion. The movement began in a workshop during the 18th Encuentro in Rosario in 2003. The only requirement to participate was to support the right to abortion. This way, the discussion focused on defining the struggle’s blueprint, unifying the dispersed forces, and the strategies to bring the issue to the center of social debate. What began as a workshop became a massive movement that flooded the streets with green bandanas—the campaign’s symbol—and impacted similar movements from Chile to Poland. On December 29, 2020, seventeen years after the first workshop, the right to abortion became national law. Since the historical event, many activists have repeatedly expressed doubt about whether the masses may ever again unite for a common cause. If the Encuentros are an outline of things to come, this year’s endless array of workshops is a sign that the movement does not need a single cause, but rather to unite in the plurality of them.

The Travesti-Trans community encountered many obstacles to gaining visibility, facing transmisia within and outside the feminist circles. Thanks to the activist efforts, the transfeminist agenda penetrated different spaces at the Encuentros and beyond, leading to significant political mobilization and the passing of the Gender Identity Law in 2011. The latter allows everyone to register according to their self-perceived gender identity, and includes complete coverage of medical treatments for transition by the public health system. Despite these hard-won rights, the Travesti-Trans community still experiences extreme gender-based violence. Since 2015, when the Supreme Court of Justice started collecting statistical data, Argentina has registered 51 travesticidios and transfemicides out of 2041 femicides. On the last day of the 30th Encuentro in Mar del Plata, Diana Sacayán, a prominent trans activist who was supposed to attend the closing ceremony, never arrived. She was brutally murdered in her apartment in Buenos Aires, in what would be the first judicially declared travesticide in Argentina’s history. Seven years later, I join this year’s Encuentro march against travesticidios and transfemicides. The names and faces of the murdered activists are present in flags and t-shirts that demand justice as everyone chants: “¡Señor! ¡Señora! ¡No sea indiferente! ¡Se mata a las travestis en la cara de la gente!” (“Sir! Madam! Don’t be indifferent! Travestis are killed in people’s faces!”)

“I am marrona [brown]. We must use this word. Argentina believes it is not racist and considers itself to be white. But we have to occupy spaces!”—a participant of the workshop Identidades Marrones (Brown identities)

When everyone speaks: conclusion as consensus

It’s Sunday and the last day of workshops. I join my compañeras from the FADU, and we head to a school that hosts Fat Activism, Afro (of African descent) Identities, and Identidades Marrones (Brown Identities) workshops. The number of workshops taking place simultaneously overwhelms us, so we strategize and divide to share the learnings afterward.

I enter the workshop organized by the Identidad Marrón collective that has engaged in antiracist activism since 2015, reclaiming the identidad marrona (Brown identity) as “children of the Indigenous people, peasants, and immigrants.” Everyone can participate; however, Brown identities lead the conversation, moderate, and take the minutes. White people are explicitly asked to attend as allies, making space for the voices of identidades marrones. “I am marrona [brown]. We must use this word. Argentina believes it is not racist and considers itself to be white. But we have to occupy spaces!” says one participant from the city of Jujuy. Another continues: “All the time, we are foreigners in our own country,” emphasizing that the Encuentro’s new name makes a difference in Argentine’s self-perception. A lawyer shares her experiences of racism at the country’s most prestigious Faculty of Law, and states: “We must pass laws to achieve [racial] equality here in Argentina.”

Meanwhile, Emilia is at the Fat Activism workshop discussing how las gordas (fatties) feel invisible; she later reports: “Someone even called out designers for not considering fat bodies in sizes, clothing, products, and spaces.” And rightfully so, compañeras from AUGE agree; most courses at the FADU—the largest design school in the country—rarely question dominant norms. Lack of norm-critically driven education produces designers who focus on the “universal” users. From architecture to industrial design, from fashion to visual communication, all disciplines center on young, thin, hetero-cis-male, white, and non-disabled people, systematically excluding the needs and experiences of non-hegemonic bodies.

On the last day of workshops, participants formulate conclusions. These aim to reach a consensus and reflect the plurality of opinions. Only persons who take part in all three sessions can suggest points, so as to guarantee that the debate doesn’t get monopolized at the last minute by partisan interests. I join the final session of the Maternidades y Xaternidades (Motherhoods and Xtherhoods) workshop, where cis and trans mothers, aunts, childfree persons, people struggling with fertility issues, sisters, cousins, and more participate. Two persons taking notes read aloud all the topics discussed for the past two days: parenting struggles in an adult-centric society, lack of government support, niñe-odio (children-hatred), vicarious violence, lack of consideration for children and parents in activist spaces, insufficient parental leave, economic struggles, mental load, fertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, guilt, and many more. The shared feeling of the impossibility of parenting in the neoliberal society fills the room.

Suddenly, one woman adds: “Condemnation of the debt!” referring to the multi-billion dollar debt contracted by Argentina’s former neoliberal president Mauricio Macri with the International Monetary Fund. The amount due will take generations to pay back, disproportionately affecting women and disidencias (identity dissidents) already facing increased precarity in the neoliberal economy where care duties remain unpaid. Under the slogan “Que la paguen los que la fugaron. La deuda es con nosotres.” (Let those who drained it [the debt] pay it. The debt is with us),” activists organized a workshop during this year’s Encuentro to discuss “the external debt as a tool of domination, and its impact on health, education and daily life.” As this topic wasn’t discussed during the previous sessions, someone contends that it should not be considered in the conclusions, and the room starts boiling.

“[The neoliberal] model of society potentiates individualism and discourages collectivity, marking parenting, rearing, and care duties as private rather than public matters.”

The progress of neoliberal policies, of which the external debt is only one symptom, impacts every aspect of the caregivers’ daily life. This model of society potentiates individualism and discourages collectivity, marking parenting, rearing, and care duties as private rather than public matters. On top of that, deregulation of the labor market serving corporate interests burdens mothers even more, who consequentially—face higher rates of precarity and poverty, trying to navigate through the interwoven forces of capitalism and patriarchy with the blunt lack of state support for social reproduction. “We can’t wait for the state! We must start the change from within our spaces,” exclaims one participant. Unfortunately, the lack of help and consideration for parents’ and children’s needs also penetrates feminist spaces, as many in the room complain. People pushing strollers can’t keep up with the pace of the marches and are relegated to the back of the columns. Upon becoming parents, activists feel excluded from their organizations as they find the working pace too fast, while others raise their eyebrows when toddlers make noise or run around during meetings. At the same time, the urgency to discuss childcare is rarely acknowledged during feminist organizing, as other topics are always more important. Lastly, many share the relentless grip of guilt for never being good enough to fulfill the impossible societal expectations of motherhood.

After a vigorous discussion, the room reaches an agreement, demanding, among others, the abolition of patriarchal adultcentrism, the prioritization of parents and children in feminist movements, and remuneration for care work. The conclusions of this and all the workshops will be read tomorrow at the closing ceremony, contributing to a broader social movement supporting the project of the law Cuidar en Igualdad (Caring with equality) and other national initiatives looking to recognize care duties as a necessity and a job. To counter the neoliberal “crisis of care,” we—in Argentina and beyond— must develop communal practices, spreading between public and private sectors and creating economic and time conditions for rearing without the pressure of productivity, equally dividing the responsibilities among diverse gender identities. Despite the shared and continuous feeling of exhaustion motherhood entails, I leave the room hopeful. United around a joint goal of making the unseen domestic and care labor visible, the community brings the struggle a step forward.

Endless feminist struggles

It is 6:30 p.m., and the last march of this year’s Encuentro is about to begin. I walk trying to find AUGE’s block amidst the never-ending column formed by Pan y Rosas, Las Rojas, La Cámpora, Mala Junta, Liberacíon Popular, Movimiento Evita, Partido Obrero, and many more; from Marxist, Trotskyist to Maoists feminists, from Peronists to Kirchnerists, from socialists to communists—feminist struggles unite. The presence of almost all parties, except for the right-wing, shows the genealogy and ideological and electoral importance of feminisms in Argentine political movements. It also creates structures to further foster the defined agendas on the ground after Encuentro. Even though the partisan bias often influences the talleres, seeking to develop strategies within electoral politics, the structure of Encuentro and how the word circulates succeeds in transforming the participants beyond the fractional lines. Finally, I reach my compañeras chanting to the rhythmic drum sounds: “Abajo el patriarcado se va a caer, se va a caer! Arriba el feminismo que va a vencer, que va a vencer! (Down with patriarchy, it will fall, it will fall! Up with feminism, which will win, which will win!)” Next to me, a toddler in its mother’s arms waves a pañuelo verde (green bandana), the symbol of the abortion-rights movement, reminding me of the hard-fought victories of past battles. Over there, pastel pink, blue and white striped banners demand a “Comprehensive Trans Law now!” Further ahead, black graffiti on the wall demands the liberation of Florencia Melo, Ester Andrea Despo, Débora Vera, and Luciana Martha Jaramillo—Mapuche women arrested last week. Unfortunately, the struggle for their freedom, land, and autonomy is not yet over.

On Monday—the last day of the Encuentro—we pack up our camp, stow away the pots, and roll up the placards. For the past three days, several compañeras cooked in the on-the-spot kitchen in one of the hangars for our group of over five hundred people, making sure that no one lacked hot water for mate and carnivorous or vegan meals. As my daughter burns up with a fever for the third day, the self-reproach is written all over my face. The organizers prepare the lists of passengers to leave for Buenos Aires, prioritizing caregivers, workers, and those who live in hardly accessible neighborhoods. These everyday solidarity practices reveal political acts—ones I often missed in other feminist spaces.

“End gender violence, stop police brutality, recognize domestic and care labor, and many more. The demands are as endless as feminist struggles.”

Together with another compañera from FADU, we embark, while the rest again stay behind waiting for the other bus, which will only arrive at 1 a.m. after a ten-hour delay. Onboard, I follow the closing ceremony on social media. The representatives of the workshops read the conclusions on the stage: the Travesti-Trans community requests social inclusion, chanting: “Ley Integral Trans Ya!” (Comprehensive Trans Law now!) A compañera from the condom workshop reads aloud: “The condom for vulvas doesn’t exist, therefore, we demand its creation!” Environmentalists demand to stop the terracide and pass the “Ley de Humedales” (Wetlands Protection law). “Iglesia y Estado, asunto separado" calls for the long overdue separation of church and state. End gender violence, stop police brutality, recognize domestic and care labor, and many more. The demands are as endless as feminist struggles. And as a final act, the ultimate consensus: through the massive applause of the participants, the next year’s venue will be the city of Bariloche. It is not a coincidence that the next Encuentro will take place just 35 km from Villa Mascardi, where the Argentinian state brutally evicted the Lafken Winkul Mapu community from their ancestral land a week ago. The movement expresses its commitment to the Mapuche people’s struggles against state repression, land grab, and cultural genocide. It seems clear that feminism in Argentina will be plurinational, lesbian, trans, travesti, bisexual, intersex, and non-binary—or it won’t be!

This article was written in the framework of my Ph.D. in Social Anthropology, financed by the Doc.CH grant of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Special thanks to my supervisors, Rafael Blanco and Sabine Strasser, for their ample support throughout my research.

Maya Ober (she/her) is an activist, researcher, educator, and designer, looking at feminist practices of design and design education. Maya is a doctoral researcher at the Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Bern.”

Title image: Top part: Workshop of Identidades Marrones. Bottom part: Closing march of the Encuentro. October 10, 2022, San Luis. (Photographs by Maya Ober and Giuliana Cordóba)