Futuress’s vertical Complaint Collective is a space inspired by feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s work. Here, we share complaints about power abuses and institutional oppressions, gathering testimonies and experiences from students and teachers in art and design schools—spaces very close to home for our Futuress community. This vertical serves as an archive of what has gone wrong—of harm and violence that too often remain unheard, unacknowledged, and unrepaired.

However, this space is not only about archiving complaints or documenting the traces of violence in higher education. It is also a site for sharing practices and initiatives that challenge institutions, reimagine art and design schools, and fabulate alternative presents—and futures. These are practices of resistance against institutional inertia, efforts to expand our political horizon, and to insist on what is possible.

By sharing these experiences, we bring forward both knowledge and lessons: the pitfalls, the failures, and moments that didn’t work, as well as the successes. What follows is one such reflection: an interview by designer and educator Katharina Brenner with Camille Circlude from the collective Teaching to Transgress* Research Group. Their name pays homage to feminist pedagogue and educator bell hooks, taking inspiration from her seminal book Teaching to Transgress. In this work, hooks argues for education as a practice of freedom, challenging traditional hierarchies and envisioning the classroom as a space for critical thinking, resistance, and transformation. The group’s name echoes this vision, aligning their work with her call to reimagine pedagogy as a radical, liberatory practice.

This interview was originally self-published by Katharina Brenner on praktiken-widerspenstiger-lernräume.de, and has been edited and expanded for Futuress.

Katharina Brenner: The Teaching to Transgress* Research Group was founded in 2017 at École de recherche graphique (ERG) in Brussels, Belgium. How did the group come to life? What sparked its creation?

Camille Circlude: It all started when Laurence Rassel, a well-known cyber-feminist, became the director of ERG in 2016. Some of us teachers saw it as an opportunity to challenge the institution’s status quo and introduce perspectives that disrupt the cis-heteronormative and male-dominated lens. I sent her an email, explaining that I wanted to do something about what I call the Gender Gap at ERG, as the topic of gender was practically nonexistent in the institution at that time. Coincidentally, Loraine Furter, another teacher at ERG, sent a very similar email to Laurence Rassel. Laurence replied, “Why don’t you work together?” encouraging us to collaborate. That’s how it began. We then invited the former student X. Gorgol to join the research group after witnessing a jury make fun of X.’s work simply because they wore high heels during the presentation.

Once our small three-person cell had been formed, Laurence Rassel, with the complicity of Nadine Plateau, strongly encouraged us not to remain isolated but instead to build a wider network across European art schools around these concerns. We then organized a first meeting in March 2017 with approximately thirty participants at ERG from diverse academic backgrounds and contexts. That inaugural day began with a circle of discussion in which each participant had a moment to introduce themselves, using any expressive means to share documents and their stories. In the afternoon, we broke into working groups to explore synergies emerging from the morning session. This day, with an expanded team was difficult to organize, particularly with regard to the budget required to bring participants together, and we were aware that a broader funding framework would be necessary to convene the network again. While awaiting a more adequate financial context (which we later secured through the Erasmus+ program), we continued to carry out actions as a group of three (Loraine, X., and me) within ERG.

“We imagined study regulations we wanted to live by. Suggestions included mandatory inclusive writing, privilege-based tuition fees, and the rejection of the compulsory medical examination.”

One of our first projects was a collective rewriting of ERG’s study regulations during the No Commons without Commoning symposium in 2018. There, we provided an open table where students and lecturers could exchange ideas and—with a lot of irony and humor—we imagined regulations we wanted to live by. Suggestions included mandatory inclusive writing, banning books by cis-male authors in the library, privilege-based tuition fees, a cuddle room, and the rejection of the compulsory medical examination. We also renamed the study regulations from ROI (le règlement d’ordre intérieur or R.O.I., meaning “king” in French) to R.E.I.N.E. (“queen”). [laughs]

At art school, mandatory medical examinations were frequently conducted by doctors inadequately trained in caring for non-normative bodies—including fat, racialized, and trans students—causing significant distress. Through R.E.I.N.E., we advocated for abolishing these examinations entirely. Though the legal mandate persists, the school administration has since required that examining physicians receive proper training and demonstrate support for LGBTQIA+ communities. In this way, our speculative intervention directly influenced a tangible change.

After the symposium, we kept working on the document and asked Laurence Rassel if she could circulate it among all the institutional members, presenting it as if it were the new regulations. Along with it, we attached an invitation to an assembly to discuss our proposal. We were thrilled that Laurence agreed to play along and publish it. So, when the teachers and students received the email, some actually believed it was real. About thirty people showed up to the assembly, where we began discussing how we could bring our fabulation to life. For instance, one idea presented was to organize a workshop on type design and gender.

“Sometimes just one sentence, or one idea, can be the beginning of something so much bigger.”

Six months later, with guest contributors who were working on the same topic simultaneously (Roxanne Maillet, H·Alix Sanyas, and Félixe Kazi-Tani), we were able to organize a joint workshop between the ERG (with Ludi Loiseau, Loraine Furter, Louis Garrido, and me) and La Cambre (Pierre Huyghebaert and Laure Giletti). This first workshop, which we called Bye Bye Binary, has since grown into an active platform and community dedicated to inclusive typography. Looking back, I realize that much of the research I’m doing today on post-binary typography and a large part of my design practice originated in that little paragraph (Article 1) of our R.E.I.N.E. fabulation. It’s a reminder that sometimes just one sentence, or one idea, can be the beginning of something so much bigger.

Seven years have passed since this protest action. How do you reflect upon it? How did it shape the institution?

Back in 2017, the text we wrote seemed super radical to us. But today, when I’m reading it again, I feel like it’s not radical at all, and many things we proposed have already been implemented in the institution since then, or could potentially be realized in the future. For example, inclusive writing is now used in all the official communication of the school (but not yet in all teachers’ courses!). Lectures about porn are now given at the school, there is a teachers’ jury with equal gender representation, greater diversity in the library, all-gender restrooms, doctors allied with the LGBTQIA+ community for mandatory medical visits, and specific welcome guidance is provided for trans students—for example, students can request to use a preferred name on their student ID cards and class rosters, even if it differs from their legal name. So, some points from our fabulation really ended up becoming reality—our protest action definitely had quite an impact. However, there is still a lot of work ahead, as, for example, the most prestigious Master’s-level courses remain disproportionately taught by cisgender white men over fifty, whose pedagogical methods often reinforce patriarchal dynamics, revealing the persistence of systemic inequalities. The security of their positions is such that replacement is only possible upon their retirement, a circumstance that generates considerable frustration and fatigue. The ERG does not exist outside broader social dynamics; rather, it reproduces the conventional power structures that characterize society at large.

“The most prestigious Master’s-level courses remain disproportionately taught by cisgender white men over fifty, whose pedagogical methods often reinforce patriarchal dynamics, revealing the persistence of systemic inequalities.”

How was the Research Group organized? What was your working practice like, and how did you collaborate in detail?

Our approach centered on posing questions to students and teachers and engaging them in discussion. For example, we organized a second large assembly to discuss student evaluation. Together with Loraine Furter and X., we produced a series of posters that were displayed throughout the school, each presenting questions directed at both students and faculty with the aim of critically interrogating assessment practices. Examples included: Are you comfortable with the authority conferred by your status? Do you engage in self-assessment, collective assessment, or other approaches, and how do you frame them? Can mere attendance in class suffice for the awarding of credits? What advice would you offer your instructors regarding assessment? Under these questions, the date of the general assembly was indicated on the posters as an invitation to meet and discuss these issues.

Another initiative we organized was a two-day summer school held in 2017 called Art Passing Trans* that brought together approximately twenty-five participants for workshops, discussions, conferences, and screenings centered on trans identity issues. The film screening and discussion on its launch day was a particularly rich moment of exchange with people with varied points of view on issues of trans identities and their representations in pop culture and the media. This introduction greatly enriched the debates that followed over the next two days.

Other highlights included the performance “Catégorie F” by Loup Kass, a student and trans non-binary artist, photographer, and videographer, the DJ workshop for women by IllSyll, and Drag King workshops (in collaboration with the association Genres Pluriels). Also, the lecture “Trans Feminism & European/American Art” led by Andréa and Luca allowed us to continue to enrich common references. Documentation also played an important role in our practice. We tried to record as many meetings and discussions as possible. We really have a lot of material!

At the time of the research group, the organization of activities was carried out solely by three members (Loraine Furter, X. Gorgol, and me). To the best of my recollection, we were allocated only a modest budget, consisting of a few hours of speakers’ fees, which in turn constrained the scope of the project as a one-off event. On the recommendation of Laurence Rassel, we applied for external grants in order to secure and enlarge the project’s funding, which ultimately led to the submission of an application to the Erasmus+ program, funded by the European Union to foster international cooperation in education.

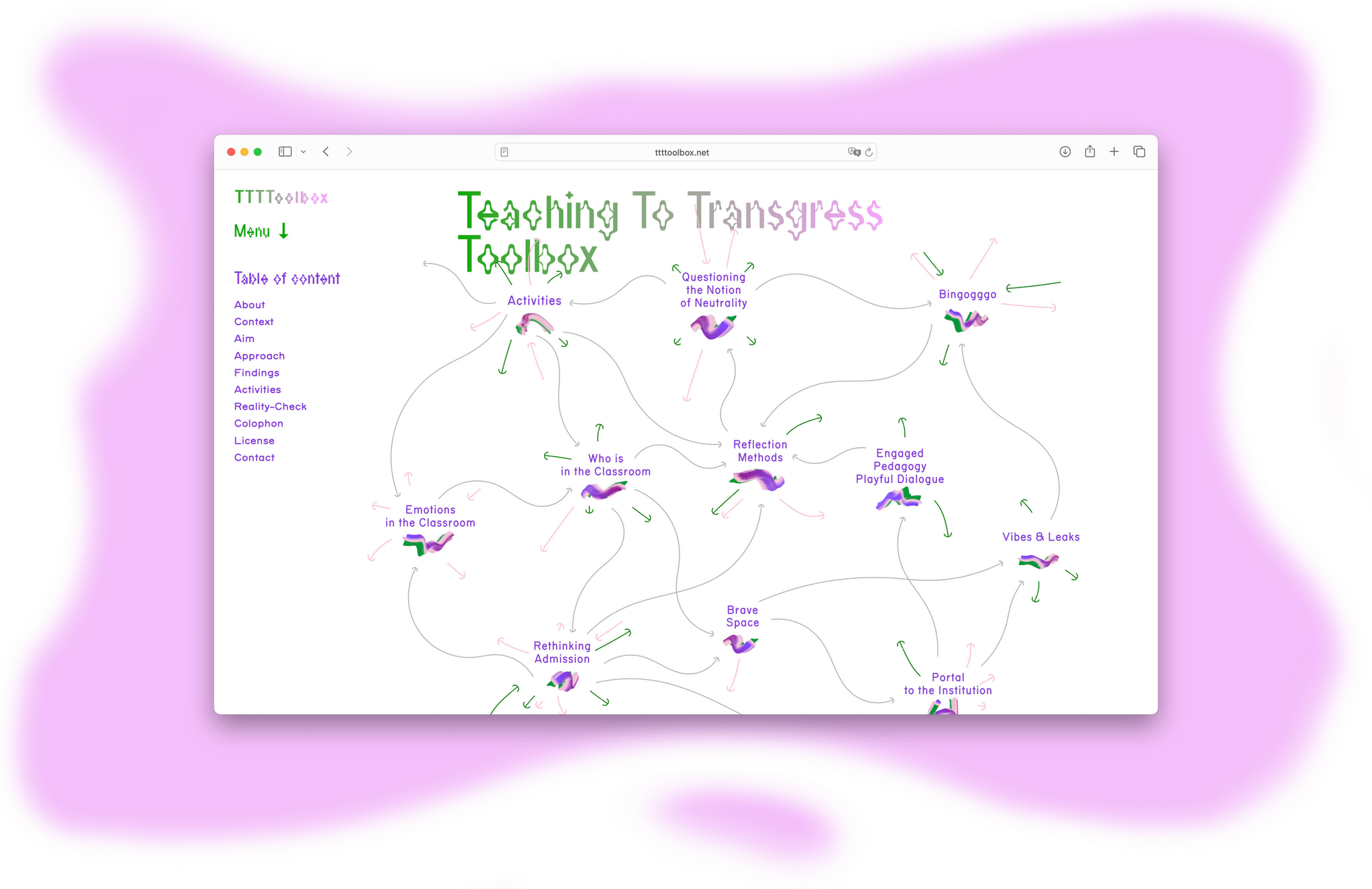

This application then led to the Teaching To Transgress Toolbox which ran from 2019–2022, right? What was the idea behind the project?

Writing the funding application for this project was a huge challenge, as we had no experience with such processes. The topic of the project was critical pedagogy in the arts, and the aim was to connect three different art schools from three different countries. The initiative sought to bring together educators already engaged with gender-related questions in order to establish an international network attentive to the urgent need to integrate feminist perspectives into art schools. This included addressing the intersections between art education and issues such as gender, postcolonialism, intersectional feminism, queer theory, and situated feminism. The program addressed a major void in art schools, whereby those interested in these issues typically work alone, outside the formal curriculum. We teamed up with Isabelle Massu from the Institut Supérieur des Beaux Arts (ISBA) de Besançon in France and the HDK-Valand in Gothenburg, Sweden where Eva Weinmayr was teaching and leading a PhD program. The first year of the project was about getting to know each other and each other’s practices. We were quite a big group of forty people assembled following a call for applications sent out by the three partner schools. Addressed to artists, researchers, activists, students, teachers, and administrators, the TTTT program invited people from various backgrounds, fields, abilities, gender identifications, sexual orientations, ethnicity, and religion to collectively explore how intersectional and decolonial approaches could activate and spread theoretical and embodied knowledge.

And what were the thematic foci of this research?

In the second year of the project, we split into groups and worked on specific topics like neutrality in teaching, emotions in the classroom, segregation with regard to school admissions, and much more. So, for instance, the piece on Questioning the Notion of Neutrality by Alexandra Eguiluz, Ida Flik, Gloria López Cleries, and Zoya Feltesse addressed the idea(l) of a “neutral” teacher. Looking at interviews and transcripts available online, we reconsidered the profession of pedagogy with an awareness of various structures of inequality, different positionalities within those, and inherent bias. We discussed that the idea of neutrality has been actively weaponized against movements for social justice. Examples of this include the “rights” of far-right, antisemitic, racist speakers to present at universities being defended on the grounds of academic freedom, or teachers failing to dismantle oppressive power structures in their classroom in favor of appearing “neutral.”

“Whenever emotional responses erupt, many of us believe our academic purpose has been diminished. People’s emotions are often invisible to others, at least until the tipping point where they break out in tears or rage.”

Another topic was Emotions in the Classroom, which was explored in Åke Sjöberg’s contribution about how the restrictive, repressive classroom ritual insists that emotional responses have no place. Whenever emotional responses erupt, many of us believe our academic purpose has been diminished. People’s emotions are often invisible to others, at least until the tipping point where they break out in tears or rage. Åke Sjöberg’s toolkit, which is available online, unpacks feelings, emotional expressions, and needs, and it aims to create a critical awareness of how emotions have been historically gendered and disregarded as a fundamental drive in learning and teaching, and in the understanding of other human beings. This toolkit provides a set of methods for being alert to emotional diversity and heterogeneity in the classroom and dealing with conflict.

We explored the controversial topic of the admissions process. The article Who Gets In? Rethinking Admission — Confronting Segregation, written by Andreas Engman and Eva Weinmayr with contributions from Ram Krishna Ranjan, examines the pivotal role of admission policies in determining access to higher education in the local context of HDK-Valand, Academy of Art and Design in Gothenburg, Sweden. Such policies are embedded within broader structures shaped by economic resources, public opinion, outreach priorities, cultural policy, national legislation, curriculum design, and institutional profiling. The group sought to understand the rationales, practices, and obstacles surrounding efforts to rethink admission policies in more intersectional and inclusive ways. To this end, they employed two primary methods. First, they conducted recorded conversations with Bachelor’s program leaders and others with practical expertise or strong commitments to widening participation, focusing on Bachelor’s programs as the main entry point into university education. Second, they engaged in role-play workshops to explore the power dynamics of admission interviews. By enacting the roles of applicants and jury members in a range of plausible and deliberately exaggerated scenarios, the group critically examined the subtle dynamics of authority, vulnerability, and decision-making, thereby sharpening their understanding of the admission process.

“Problematic language is so often integrated or internalized as commonplace [...] and spread, even involuntarily, by people who have not yet undergone a process of deconstructing their privileges.”

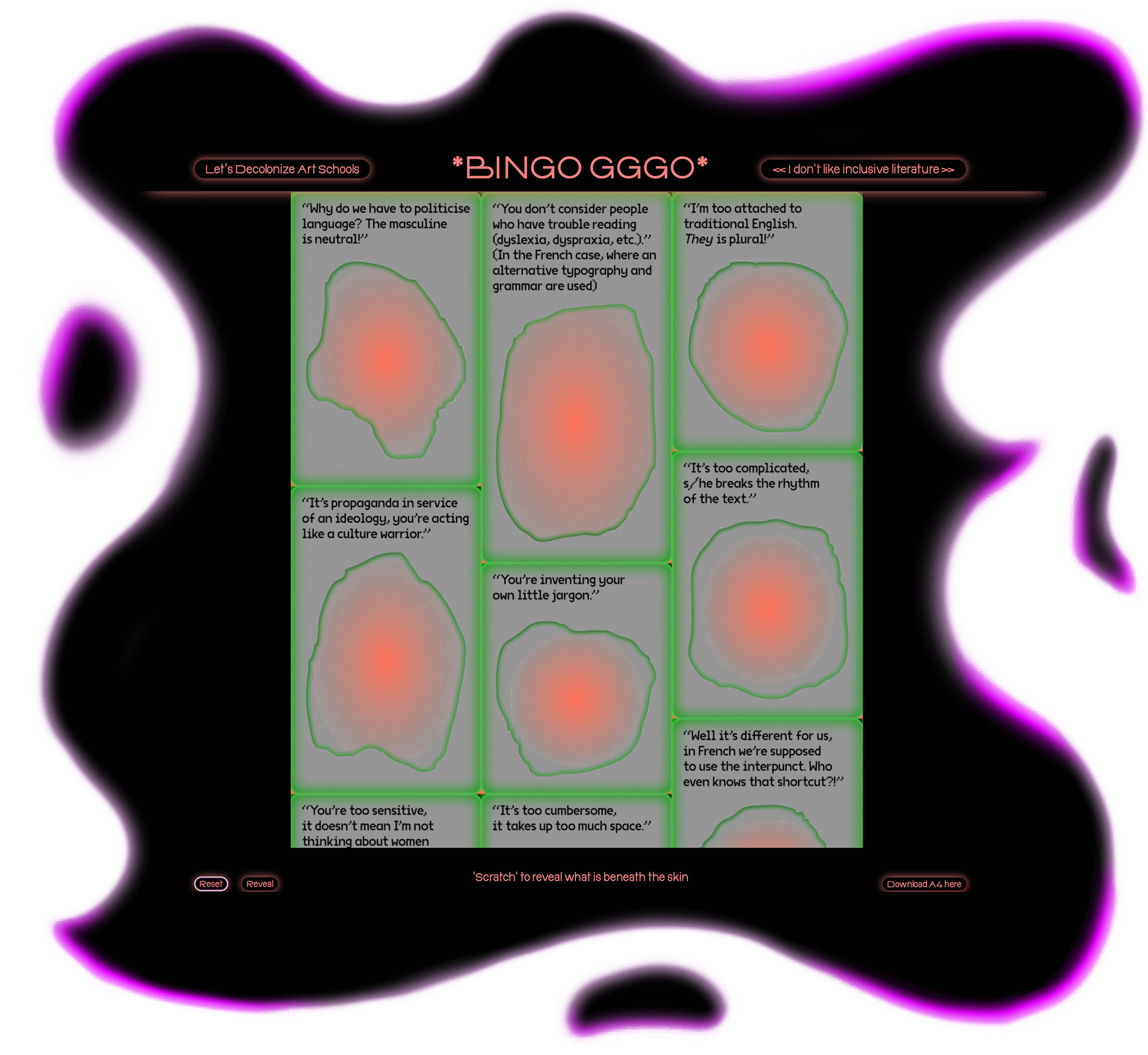

Yet another theme, to which I myself contributed, was my favorite topic about inclusive writing, with a focus on my design of the “I Don’t Like Inclusive Writing” Bingo and “Let’s Decolonize Art Schools” Bingo, which are part of the Bingo gggo group with Chloé Elvezi, Enz@ Le Garrec, ReussMaureen Leprêtre (with inputs also from Elsa Abderhamani, Nino André, Céline Chazalviel, Solène Collin, Martha Salimbeni, Chloé Stevenoot, and Daphné Targotay). The point is to use these bingos in a hostile context and to be in a position to identify systemic phrases spoken by others. Bingos thus help to highlight problematic language that is so often integrated or internalized as commonplace. These systemic attacks insidiously infiltrate language and are spread, even involuntarily, by people who have not yet undergone a process of deconstructing their privileges. These attacks take the form of repeated phrases spoken by different people. These people can often leave us voiceless. Our bingos can be a playful aid, a tool that provides both short, ironic, and incisive responses, as well as more pedagogical arguments for those who need them. These two levels of response become efficient and well-constructed counter-arguments in order to sensitize and teach others. Of course, it is still necessary to have a willing partner. These two bingos were subsequently transformed into a website featuring a playful scratch-and-reveal effect, as well as into A4 sheets made available for download, home printing, and distribution.

Looking back, how did the project turn out, and what did you learn along the way?

For me personally, the project was quite challenging. We had planned to meet in person, and then in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic interfered, so we mainly met online. It was a particularly difficult shift to have all meetings held online, given that the very purpose of the program was to build a network enabling individuals engaged in feminist practices to overcome their isolation. Instead, they once again found themselves isolated, this time behind their screens. In addition, the contexts of the respective universities differed substantially. Our colleagues at Besançon were struggling with the direction and the academic staff of the school, who were accused of racism, sexual and power abuses. Testimonies from victims multiplied on social media through the collective Balance ton école d’Art (translated as “Expose your art school,” echoing sector-specific adaptations of the #MeToo movement). Understandably, our TTTT’s partners were so preoccupied with this situation that it was difficult for them to be involved in other things at that time. We, as the Teaching to Transgress* Research Group, tried to support them with an open letter in which we supported all the students, former students, and staff at ISBA who had the courage to publicly denounce these facts. We also want to point out that the mere fact that ISBA Besançon is a partner in the TTTT program does not safeguard the administration at ISBA from taking responsibility for the abuses committed by members of staff at the art school. Unfortunately, after several months, the case in the hands of the judiciary was eventually dismissed, leading to discouragement among those at ISBA who had pursued this struggle. This outcome illustrates the inability of the French justice system to adequately address cases of assault, harassment, and rape. Notably, in 2016, at least 73% of cases involving sexual violence were dismissed without further action.

After all, the TTTT program was meant to foster allyships and to stand up for each other in difficult situations. On top of that, the teacher coordinating the project at Besançon was on the verge of burnout and eventually stepped away from the project. At the Gothenburg school, there were also issues with financial management. As a result, we ended up completing the project alone at ERG, while also trying to finalize the report. It was an intense experience, most of which we managed to document on our website ttttoolbox.net.

The project concluded in 2022 after running for nearly five years in total. Today, all group members are engaged in new projects, practices, and research. Yet, many art and design schools still have significant changes to make. What advice or recommendations would you offer to students and teachers seeking to spark change from within their institutions?

One aspect that I am very dissatisfied with is that many of the teachers involved were white. At ERG, we were aware that if we wanted to apply an intersectional feminist lens, it was essential that BIPoC people were involved in the structure itself. The representation of BIPoC individuals within the organizational structure of Teaching to Transgress Toolbox should have been even more prominent, particularly given that a text by bell hooks was also adopted as the title of the program. During preparation meetings, Loraine Furter consistently raised concerns about the lack of diversity in the teaching staff, and she eventually stepped down from her position and transferred her teaching hours to Stéphanie Vilayphiou and Sarah Magnan, who joined the ERG organizing team. So we intentionally made room for this diversity. However, though we asked the two other partner institutions to do the same, in the end, they didn’t—and I still don’t know why. Perhaps at ERG we were better equipped to recognize the urgency of these questions because the “After Empire” seminar had just taken place in 2017. The seminar had brought to ERG thinkers such as sociologist Paul Gilroy and the filmmaker Amandine Gay, who directed the Ouvrir la voix movie (Speak Up:Make your way). This seminar framed a moment that made it possible—indeed, necessary—to confront structural whiteness within our own institution. It was during the workshop with Amandine Gay, for example, that I first became conscious of my own whiteness; at the time, even pronouncing the term “whiteness” was relatively new in the context of an art school.

Despite the fact that the organizing team of TTTT, as well as many of the guest speakers, were predominantly white, a considerable number of BIPoC participants enrolled in the program—and were subsequently confronted with its whiteness. It was a real problem. In an attempt to counterbalance the whiteness of the organizing team, the ERG invited BIPoC guest speakers, such as the artist Joëlle Sambi and Sylvia Iweanya, as well as Nassira Hedjerassi from the bell hooks Institute. However, this gesture remained insufficient and, above all, did not constitute a structural change within the organization. Moreover, in the subsequent sessions at HDK-Valand and ISBA Besançon, this effort was not repeated: the majority of invited speakers selected by these two schools for the online sessions were also white.

So, I definitely learned a lot about what I would do differently as a white person! I shouldn’t have had to learn all this on the spot, and certainly not at the expense of BIPoC participants involved; I should have been prepared in advance. Now I understand that it is my responsibility to educate other white people. I only wish someone had done that for me before I naively embarked on this project.

“It is time to organize, and it is essential that such programs within institutions continue to exist.”

I am completing the revision of this interview in September 2025, just as the “After After Empire” seminar has just taken place at ERG, once again with the presence of Paul Gilroy, nine years after the first seminar! During these days, we collectively confronted the extent to which fascism has intensified in the intervening years, shaped by the geopolitical context we are living through today: the alarming rise of racism, fascism, sexism, and transphobia worldwide, and particularly in the United States. At the same time, however, many people in the audience were BIPoC students, which indicates that the shift in representation we had hoped for in 2017 has begun to take root, though belatedly. The teachers, too, have become somewhat more diverse. While these developments cannot be attributed to our initiative alone, they suggest that change, though uneven and fragile, remains possible, even in the face of a global political climate that grows increasingly hostile. More than ever, it is time to organize, and it is essential that such programs within institutions continue to exist. Though our involvement in TTTT has concluded, the reflections it sparked live on and continue to resonate.

This interview was originally self-published by Katharina Brenner on praktiken-widerspenstiger-lernräume.de, and has been edited and expanded for Futuress.

Camille Circlude (they/them),

author of La typographie post-binaire, is an interdisciplinary artist, designer, and researcher who explores the intersections of language, gender, and type design. Camille, who has a Master’s degree in Gender Studies, is a member of the

Bye Bye Binary collective, developing experimental typographic practices that challenge binary structures and focus on the political dimensions of graphic design. Based in Brussels, Camille is part of the design studio

Kidnap Your Designer, and teaches at

ERG. Together with

Enz@ Le Garrec, Camille is currently developing a research project entitled

“Post-binary typography: research on the uses, appropriations, and pollination of typefaces,”

funded by the Fonds de la Recherche en Art.

Katharina Brenner (no pronouns) works at the intersection of queer feminism, institutional critique, radical pedagogy, and activism, developing formats such as collaborative learning environments, publications, and public events. Katharina is currently working as a Research Associate in the project FemPower at the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design Halle in Germany. Katharina studied Visual Communication at the University of the Arts Berlin in Germany, the Estonian Academy of the Arts, and the Kassel University of Art in Germany, and co-initiated the student-organized seminars Klasse Klima and Eine Krise Bekommen.

From 2017–2022, Loraine Furter, X. Gorgol, and Camille Circlude were part of the Teaching to Transgress* Research Group, which is an experiment on gender and queer issues, postcolonialism, and intersectional feminism, within the context of the pedagogy and practice of the arts. In 2019–2022, this project has taken the form of a European Erasmus+ program, Teaching To Transgress Toolbox, together with the ERG (École de recherche graphique) in Brussels (Belgium), the Institut Supérieur des Beaux Arts (ISBA) de Besançon (France), and the HDK-Valand in Gothenburg (Sweden).

The organizer team included: André Alves, Rose Brander, Camille Circlude, MC Coble, Andreas Engman, Loraine Furter, Xavier Gorgol, Sarah Magnan, Isabelle Massu, Emilie McDermott, Laurence Rassel, Stéphanie Vilayphiou, Eva Weinmayr, Lucy Wilson

Participants: Nino André, Emilie Bauer, Flo*Souad Benaddi, Lani Fusako DuVall, Alexandra Eguiluz, Chloe Elvezi, Zoya Feltesse, Ida Flik, Inga Gunnlaugsdóttir Söring Kolbrún, Danielle Nicole Heath, Helio Hoarau, Samantha Jane Hookway, Reuss Maureen Leprêtre, Gloria López Cleries, Yusha Ly, Aroun Mariadas Savarimouttou, Fallon Mayanja, Emmanuelle Nsunda, Åke Bo Martin Sjöberg, Sylvain Souklaye, and Nontokozo Survive Tshabalala.

The title of this vertical, Complaint Collective, is an homage to Sara Ahmed, whose ideas have been and continue to be extremely influential to Futuress. In killjoy solidarity, we stand!