Trigger warning: Before you start reading, please note that there are graphic descriptions of violence in this text.

“My [design] teacher told me he wanted to pour latex over me to have a blow-up doll he could fold up and put in his suitcase and use on his holiday. When I filed a complaint with my counselor, I was told ‘that’s just him’ and I should just ‘deal with it’.”

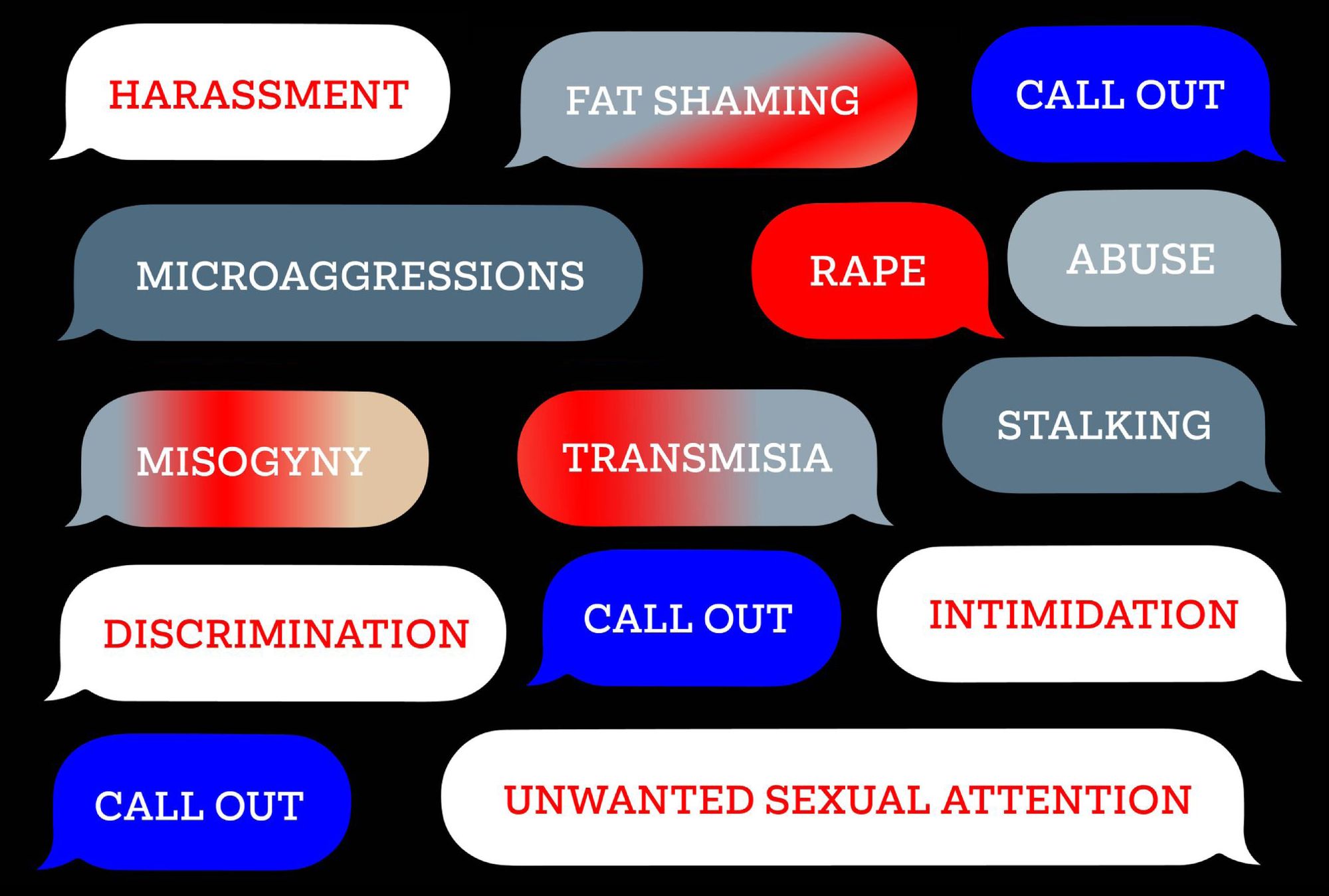

This is one of 72 anonymous testimonials of sexual misconduct, racist rhetoric, misogynist remarks, or generally inappropriate behavior said to have occurred at art institutions in the Netherlands. They were published as a series of tiles on @calloutdutchartinstitutions, an Instagram account that went live in the last weekend of October 2020. The posts detailed numerous alleged instances of harassment, discrimination, abuse, and intimidation; as well as emotional and physical violence, including rape. They cite museums, cultural institutions, and galleries across the country as sites where violence was allegedly perpetrated; but mostly, they cite art schools—the vast majority of art schools in the Netherlands, in fact.

“I definitely feel that an account like @calloutdutchartinstitutions is necessary. My school does not take complaints seriously, and does not keep them anonymous”

“I definitely feel that an account like @calloutdutchartinstitutions is necessary,” says one anonymous student from an institution associated with several allegations. “My school does not take complaints seriously, and does not keep them anonymous. I know for a fact that a tutor told a teacher in question about my complaints, because I noticed a clear change in his behavior toward me.”

The Instagram account stopped posting after seven days, and three months later it went completely offline. This leaves us with the question: what happens after a call-out?

From the silver screen, the ripple effect of #MeToo first reached the Dutch music industry in the summer of 2020, via two Instagram accounts dedicated to rumors and accusations of sexual misconduct by Dutch male musicians. @abusers_nl, the most popular account with over 12,000 followers, featured countless anonymous alleged instances of abuse, intimidation, and rape by men with some kind of claim to fame—many of whom reside in Amsterdam, where I live.

“One could argue, @abusers_nl amplified a whisper network that had already existed, making such word-of-mouth warnings more effective.”

While some of the names listed at @abusers_nl shocked me, most of them sounded familiar and unsurprising—I had been warned about them before by friends and colleagues in the club where I work. As I read the name of an acquaintance who has regularly bothered me with inappropriate messages on Facebook and Instagram, it was strange to realize that I’ve been right to avoid him all these years, and at the same time I felt distressed thinking about the others that might potentially have fallen victim to him. One could argue, @abusers_nl amplified a whisper network that had already existed, making such word-of-mouth warnings more effective.

As the summer faded, so did the public interest in the stories, and the @abusers_nl account was deleted. But then that fall, the #MeToo whirlwind on social media picked up again. This time, it was finally headed toward the visual arts scene in the Netherlands.

It was the Dutch newspaper NRC that first broke a story on rape, violence, and stalking allegations against a renowned Dutch visual artist. The alleged acts described in the report had been going on for years, while the artist in question remained popular and successful. The article attests to how women repeatedly warned art institutions, galleries, and art schools about him, but to no avail. The weekend following this article’s publication, @calloutdutchartinstitutions appeared. Within a week, 72 allegations of sexual misconduct, racist remarks, intimidation, and other worrying behavior by staff members of galleries, museums, and art schools all over the country were live, with more and more comments and shares flaring beneath each post by the hour. Some posts detailed recent incidents, while others went back decades, with several names being repeatedly cited. The account quickly gathered over 9,000 followers, with Instagram users commenting on the posts with their own public profiles, saying things like “#notsurprised” and tagging the art institution in question.

“Art schools—supposedly safe spaces for students to develop their practice and kickstart their careers—were accused of turning a blind eye to sexual harassment, insults, and racist remarks from professors, students or staff.”

Art schools—supposedly safe spaces for students to develop their practice and kick-start their careers—were accused of turning a blind eye to sexual harassment, insults, and racist remarks from professors, students or staff; as well as refusing to provide the victims with sufficient help. Several posts describe problematic pedagogical approaches, for example: mandatory assignments that forced students to engage in cultural appropriation, assignments dealing with—and therefore triggering—personal traumas, and assignments exposing the intimate bodies and lives of students. Several students claimed they filed complaints and were met with hostility and further ridiculed by their institutions.

For professors directly confronted with criticism on the account, it seems that some had little to no self-reflective capabilities. According to an email provided by an alumnus, one professor messaged his entire school two days after being cited on @calloutdutchartinstitutions to declare that his behavior was well-intentioned. He blamed generational differences for the way in which his statements were wrongly interpreted, arguing that his remarks intended to prepare students for the “real world.”

A professor at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts in The Hague, KABK, was repeatedly named by @calloutdutchartinstitutions for allegedly inviting young female students to his place after gallery openings, and other problematic behavior. “There were many stories of sexual relations between him and the students,” alleges one anonymous submission on the account. One of his colleagues is also said to have made sexual remarks about the way his female students dressed, while also urging them to “have some fun with men” and use those experiences as inspiration. As soon as @calloutdutchartinstitutions was online, students responded to the allegations against these two professors by pasting posters on the walls of the school, imploring that the institution “protect your students” and “reevaluate your staff.” The school organized a meeting in an attempt to create space for complaints. However, according to my anonymous source, much to the horror of many students, the two professors in question were present at the meeting and claimed they were aware of the allegations, but refused to leave. The two KABK professors have since been and remain suspended, and the school says that an internal investigation is underway. The KABK also claims to be taking several other actions, including improving communication protocols and guidelines. Also, in 2021, they listed a new job post for “Diversity & Inclusion”—a position which had not existed prior.

“Submitting an anonymous claim seems to be a last resort: with it, students can warn others from the comfort of anonymity.”

Interestingly, the suspension of said professors took place speedily within five days of the publication of the newspaper article and the emergence of @calloutdutchartinstitutions, while the anonymous claims suggested that the school was reluctant to take complaints seriously prior to that. Incidents, such as the one mentioned prior when a professor allegedly told a student he wanted to make a latex blow-up doll of her, had apparently been met with the response: “just deal with it.” Arguably, @calloutdutchartinstitutions is necessary because art schools don’t seem to be listening when students provide them with criticism of staff. Submitting an anonymous claim seems to be a last resort: with it, students can warn others from the comfort of anonymity. Also, survivors are able to take refuge in anonymity as they speak out against powerful individuals. However, some argue that anonymity itself is part of the problem. As one commenter complains in a post: “I think this is dangerous. Though this story could very well be true, it is entirely based on gossip.”

A handful of similar comments hypothesized that posts on the page were false. After a week of posting, @calloutdutchartinstitutions announced that it would stop adding new testimonies. “Let it be clear: this account was never a solution, rather a tool to show the critical need for direct action and accountability from cultural institutions with pretty facades and rotten infrastructures,” the anonymous moderator(s) announced, claiming they were unable to keep up with the overwhelming amount of messages that they received. The moderator(s) urged people who still wanted to address their experiences with misconduct to use Mores.online, the central disclosure office for undesirable behavior in the (performing) arts, film, and television sectors. They stated that posts would not be deleted, nor would the profile be removed, but it would “stand as a testament, and a reminder of the powerful act of speaking up and uncovering the truth behind ‘hushed’ tones.” In February 2021, however, the account and its associated email suddenly went completely offline, and we were unable to establish the reasons behind the account’s removal.

K., an anonymous student at Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, was disappointed when the @calloutdutchartinstitutions first stopped posting. She describes having had an incident involving a teacher, and subsequent trouble addressing it at school. Currently, the Rietveld Academie only accepts complaints as formal written letters addressed to the secretary of the “complaints committee”—a three-member team appointed every four years, which does not accept anonymous complaints, nor complaints about incidents taking place over one year before it is reported. Since January 2021, however, the school has started appointing “staff confidentiality advisers” to help with those issues.

“Rietveld is quite conservative in their approach to dealing with behavioural issues,” says K. “They’ll only take action when there’s a formal complaint with sufficient proof to suspend a teacher, as if that is the only thing within their power. This is a very narrow understanding of responsibility: there’s actually a wide variety of other things they could do to intervene and to ensure a safe working space, as well as actively monitoring their students’ and staff's health and safety—instead of passively waiting for someone to file a complaint. Other incidents, like microaggressions (which may demonstrate consistent patterns of more complex toxic behaviour), don’t get taken seriously at all.”

Many of K.’s peers at Rietveld had also sent in submissions to @calloutdutchartinstitutions that did not get posted. In response, K. and a group of other students started Untold Rietveld, a channel that collects complaints and accusations, but doesn’t post them publicly. “We were moved to act by the institutional lack of interest in simply hearing these stories, which could not have been shared under the formal procedures existent at the time.”

“Rietveld students that reach out to us have usually already tried to address their situation according to the protocols in place, but to no avail,” says K. Many have even decided not to pursue their complaints, because they could not see any consequences other than retaliation, which would be to their own detriment. “With the more serious issues, we try to support people with a peer-to-peer forum, or by referring them to psychologists or even lawyers. Additionally, until better policies are in place and victims can speak safely, we want to monitor recurring and systematic issues and try to address them if we can. We’re very wary of victim-blaming the people confiding in us, so we handle every situation with delicate care.” Since Untold Rietveld began, the complaints poured in, so K. prioritizes dealing with what has already been submitted over collecting more complaints through social media. “We need to use our time to handle the things that are already reported. This was an emergency and temporary solution, not meant to last. We hoped it would trigger change and would push for better procedures to be introduced. We started reaching out to people from other art schools and organizations, so we have more hands, more brains, and more hearts to deal with all of this.”

All in all, anonymous accounts like @calloutdutchartinstitutions face a lot of backlash. Critics claim that formal ways of making a complaint are installed to protect people from reckless accusations with no basis in reality. But does the risk of false accusations of sexual misconduct and sexual assault outweigh the necessity of safer spaces for these stories?

“For many, reporting is not an option; either the sexual abuse took place without violence, or the violence and coercion cannot be proven.”

At the end of the day, it is highly unlikely that an Instagram post with a rape allegation will lead to criminal prosecution, as victims know all too well. Even if an Instagram post could find its way into a police report, only 37% of reported rapes result in criminal charges in Holland. Furthermore, in the rare instances when a case does move forward, the process is usually slow and difficult. Survivors also struggle with the Dutch penal code, which until December 2020, defined rape as only when there was proven violence or coercion involved. This left out cases in which the perpetrator continues after one communicated disconsent, or was unable to consent due to being under the influence, for example due to intoxication. Those instances of rape are also mentally scarring, and have been acknowledged by progressive laws in countries like Scotland since 2010. For many, reporting is not an option; either the sexual abuse took place without violence, or the violence and coercion cannot be proven. We have yet to see if the new legislation leads to more justice for survivors. Until then, it is hardly surprising to see accounts like @abusers_nl and @calloutdutchartinstitutions emerge, when the law does not sufficiently protect rape victims, and when art schools cannot guarantee the safety of their students.

One initiative that addresses the needs of survivors is F-Razzor, a fundraising campaign realized in collaboration with Platform BK to raise awareness about current issues around the abuse of power, sexism and inequities in the Dutch art field. Over sixty international artists who attended the Rijksakademie between 2014-2017 have donated artworks for the sale, which will go live on March 8. The funds raised will go towards supporting victims of sexual abuse with legal fees and psychological counseling expenses, as well as supporting a newly founded the artist-led organization Engagement Arts NL, dedicated to tackling sexual harassment, sexism and abuse of power in the arts in the Netherlands.

“The account’s sudden disappearance from the websphere is a reminder of how quickly these efforts and voices can go silent.”

Anonymity may allow people to make false allegations without any repercussions, but it also allows victims to share their stories without being dismissed, expelled, ridiculed, or put at risk of retaliation by the perpetrator. If @calloutdutchartinstitutions is illustrative of something, it is that survivors are tired of not being heard, and that their stories are going to see the light of day, one way or another. This has led to many people in the art world having to rise to the occasion—pessimistic about the current state of affairs, yet devoted to making a change. The Instagram account sparked a chain of responses from the likes of Mores.online, Platform BK, F-Razzor, as well as countless new student initiatives, which are now all working toward a more equal environment in the arts. At the same time, the account’s sudden disappearance from the websphere is a reminder of how quickly these efforts and voices can go silent.

As K., cofounder of Untold Rietveld, proudly said: “Our channel, together with all the initiatives that followed in the aftermath of the NRC-article, has already triggered change. Rietveld is now looking for ways to improve their intake of complaints, and is more willing to listen to students’ opinions. Things are looking up, but there is still a lot of work to do.”

Tessel ten Zweege (she/her), is feminist-in-chief at PISSWIFE, a feminist collective making zines about intersectionality and art. In March 2020 she made her debut as a filmmaker with a documentary about her experience with intimate partner violence. She recently graduated from the University of Amsterdam and writes for OneWorld, VICE and Bedrock Magazine.

If you have experienced misconduct within a Dutch art institution and are looking for support, you can contact: Mores.online, Safe Women NL, or Engagement Arts.

The title of this vertical, Complaint Collective, is an homage to Sara Ahmed, whose ideas have been and continue to be extremely influential to Futuress. In killjoy solidarity, we stand!