For over a year now, I’ve kept a journal that has been slowly filling up with dream entries, detailing my mind’s fantastical adventures each night. I originally began this journal in an attempt to learn how to lucid dream, and to later share these adventures with friends and family. My dreams can be as ridiculous as watching a girl transform into a hamster through jumping into a giant bouncy ball; as much as they can be intensely emotional, frightening, and devastating. However, they can also be just as beautiful. Mutual dreaming is the concept of experiencing the same dream with somebody else at the same time, and although there’s no scientific evidence to back this up, countless personal anecdotes suggest its possible existence. A month ago, I dreamt that my friend in Hong Kong returned to our school in the U.S.A., and although I have hardly seen her in two years, we were talking like no time had passed. When I woke up, I messaged her and to my surprise, she replied saying she had also dreamt about returning to school the night before.

While reading back through my journal, I realized my dreams aren’t simply a way for me to escape the realities of my tangible world; they are also a simultaneous reality that I enter in my slumber. In a purposeful act of self-care and forgiveness, allowing myself to sleep and explore the depths of my relationships, emotions, and humor is allowing myself to be whole.

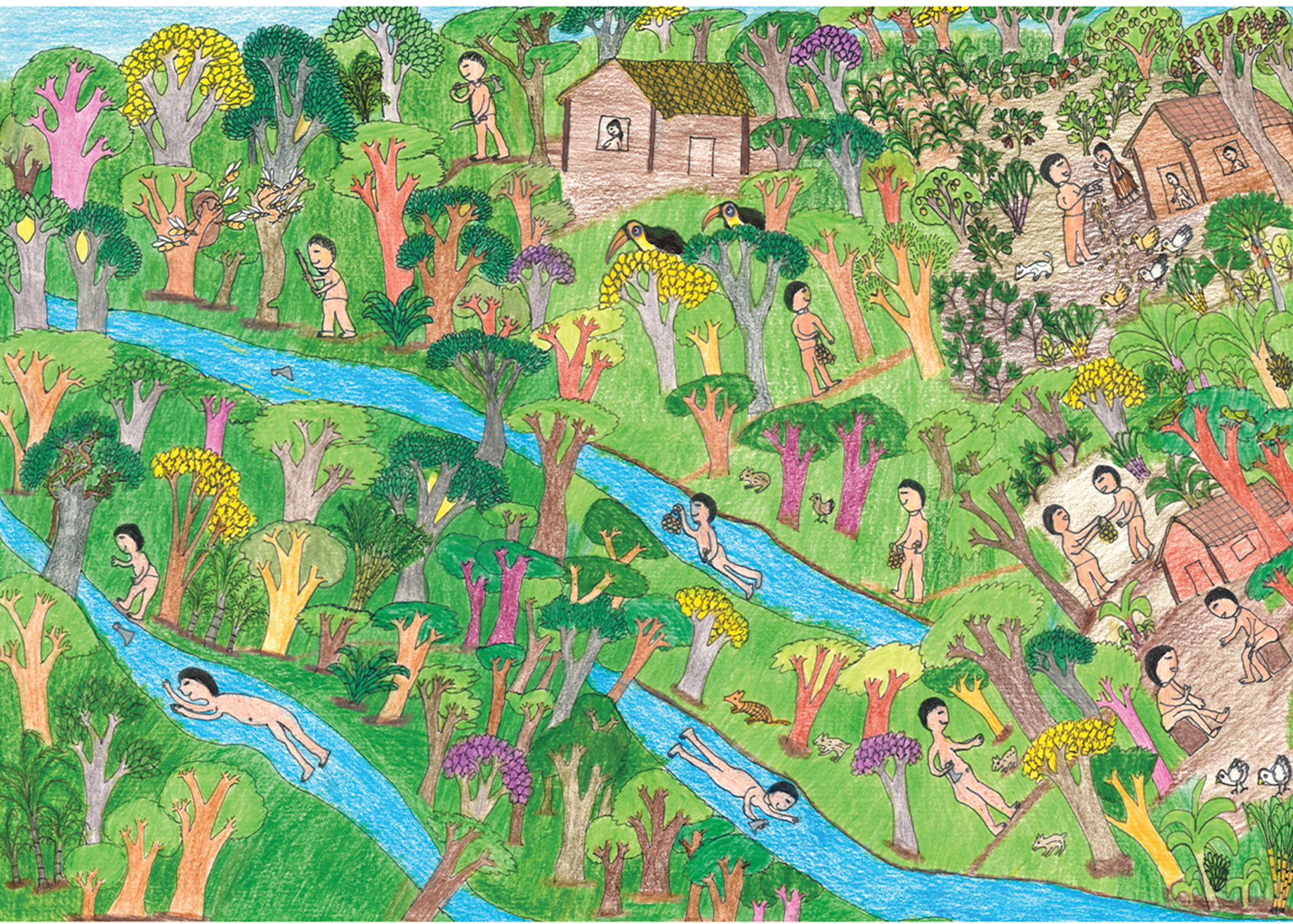

Dreams are political—they’re an act of defiance against the hegemonies of capitalism and white supremacy, allowing the mind to mold and explore their own worlds without the oppressive constraints of time and space. Similar to science fiction and fantasy, dreams don’t rely on the conditions of the present reality to forge new identities and communities. Marginalized people are free to imagine an emancipated world in which colonialist powers no longer exist, or humans seek to repair their relationship with nature. It can be otherworldly and liberating to imagine a journey escaping the systemic violence of our earth to a village in outer space with completely foreign customs.

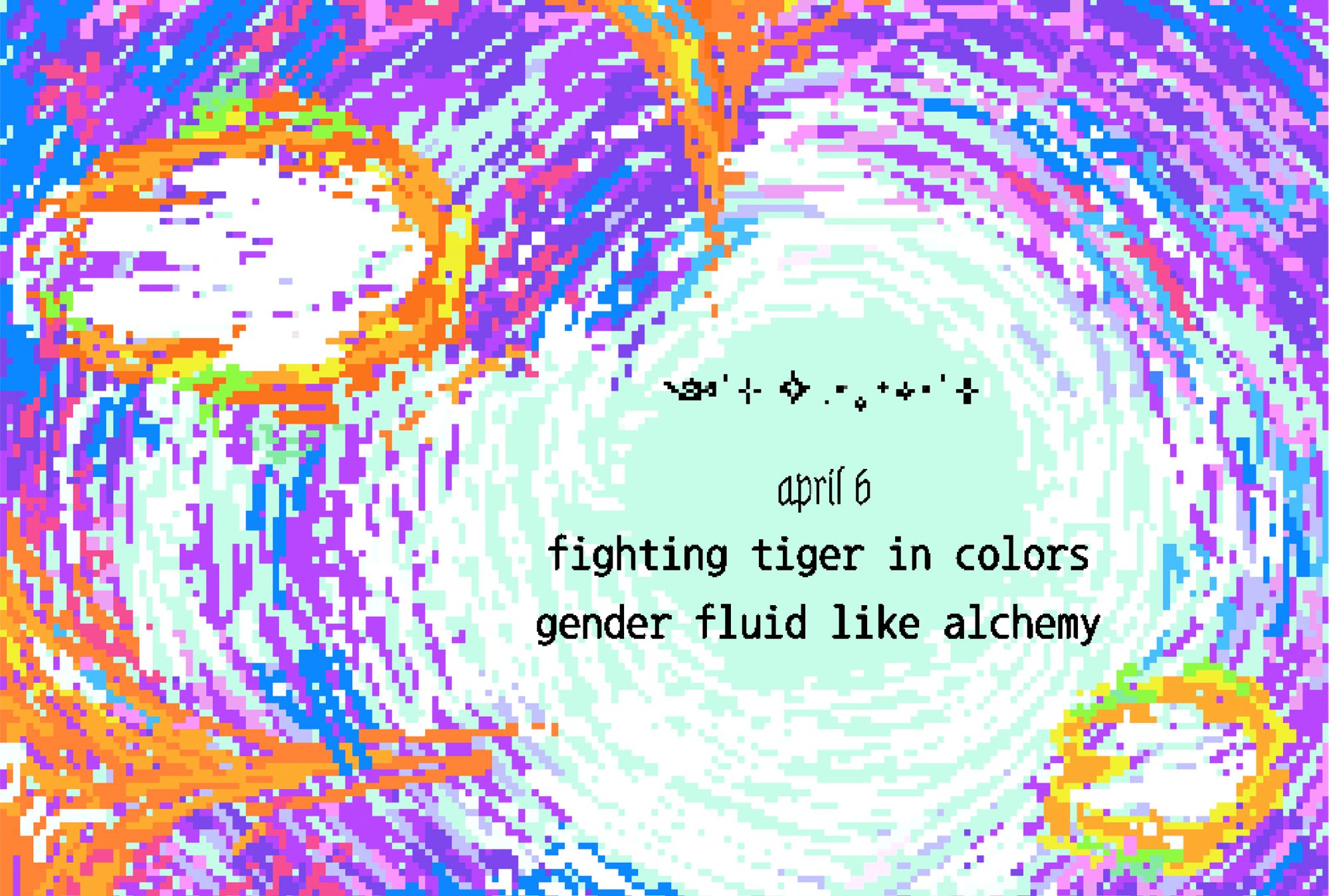

The breadth of my political identity as a queer Chinese American blooms from the abstraction of my dreams, which is then informed by the tangibility of its surrounding community. In the same sense, my nighttime dreams communicate with my political dreams: it asks what kind of world I want to live in, now and in the future. Asleep or awake; unrealistic or realistic; immaterial or material.

Dreaming as a framework for resistance

Whether working or socializing, all aspects of our lives have been permeated by capitalist infrastructure. It conditions us to think that we need commodities to perform daily tasks, such as dating apps that reimagine socialization, or chairs that optimize productivity. In Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Jonathan Crary argues that all human necessities such as hunger and sexual desire have been made into “commodified or financialized forms,” injecting them into a social culture that mutates time into capital. This culture encourages its inhabitants to devote increasing amounts of time to labor and production of more wealth. In this dystopian form of reality, Crary explains, “sleep is an uncompromising interruption of the theft of time from us by capitalism.” The U.S. government is one of the worst perpetrators of time theft—an ongoing research project by the Pentagon aims to reduce the amount of time a soldier needs to rest and to optimize the amount of time they can fight. Inevitably linked with imperialism and white supremacy, this forceful manual deprivation of sleep is, as Crary notes, “the violent dispossession of self by external force, the calculated shattering of an individual.”

Inevitably, sleep isn’t exempt from capitalism’s reach. Sleeping and wakefulness medicine or sleep tracking apps have drastically distorted our natural practice of rest. So, is there another layer within sleeping that is preserved and optimistically untainted? Dreaming can be dissected as a practice of resistance because, while it is by no means untainted, it remains largely untouched by the extent of capitalism. Common dreams include showing up late to work or taking exams—situations that we are conditioned to fear so intensely that they invade our subconscious. Meanwhile, a lack of dreams (or of recalling them) also mark the presence of capitalist desires, often indicating inadequate rest since dreams tend to be the most vivid during concentrated sleep in the REM stage. We’re habituated to go to bed absurdly late and wake up before sunrise, wearily self-imposing the destructive “dispossession of self.”

“The complexity and depth of dreams prove to be a powerful tool for criticality. Its arbitrary nature directly rejects capitalism and imperialism’s ideologies that are founded on logic, reason, linearity, and rationality.”

However the essence of dreams beckons it as a framework for resistance. They’re illogical, unrealistic, and untethered to time and space, with endless possibilities that challenge the boundaries of your mind and imagination. They can seem as realistic or unrealistic as your subconscious dictates, while also revealing inner truths about your emotions or relationships. You’re free to imagine a utopian existence free of suffering—or you could find yourself in a dystopia corrupted by otherworldly beings. Because dreams are ultimately informed by our realities, they can be as disturbing as they are liberatory, revisiting trauma in grotesque detail or amplifying fears in the form of nightmares. Yet, the complexity and depth of dreams prove to be a powerful tool for criticality. Its arbitrary nature directly rejects capitalism and imperialism’s ideologies that are founded on logic, reason, linearity, and rationality.

Speculative futures and imagined worlds

My original interest in the temporality of the marginalized body began with my interest in speculative fiction, which initially seemed like a wondrous and expansive realm of alien worlds and wonderfully impossible technology. However, I soon became disillusioned by the whiteness, privilege, and lack of nuance within the speculative fiction sphere, which Octavia Butler most notably criticizes through her essays and sci-fi novels.

The term “techno-orientalism”—now often referred to as “Asianfuturism”—acutely interrogates how the white speculative gaze racializes Asians and forces them through time and space. In Euro-American media such as Blade Runner or Cloud Atlas, the future is often visualized as East Asian urban environments—neon lights akin to those in Hong Kong, or towering Tokyo skyscrapers. The inhabitants of these cityscapes are cold, intellectual, and yet primitive; whose lack of whiteness only serves to preserve and maintain white hegemonies. Not only does this strip agency from these imagined Asian bodies, but it also perpetuates the continued dehumanization of Asians in the present reality by othering them as robotic, passive, or threatening. I ask myself, do I accept this imposed and orientalized future for myself?

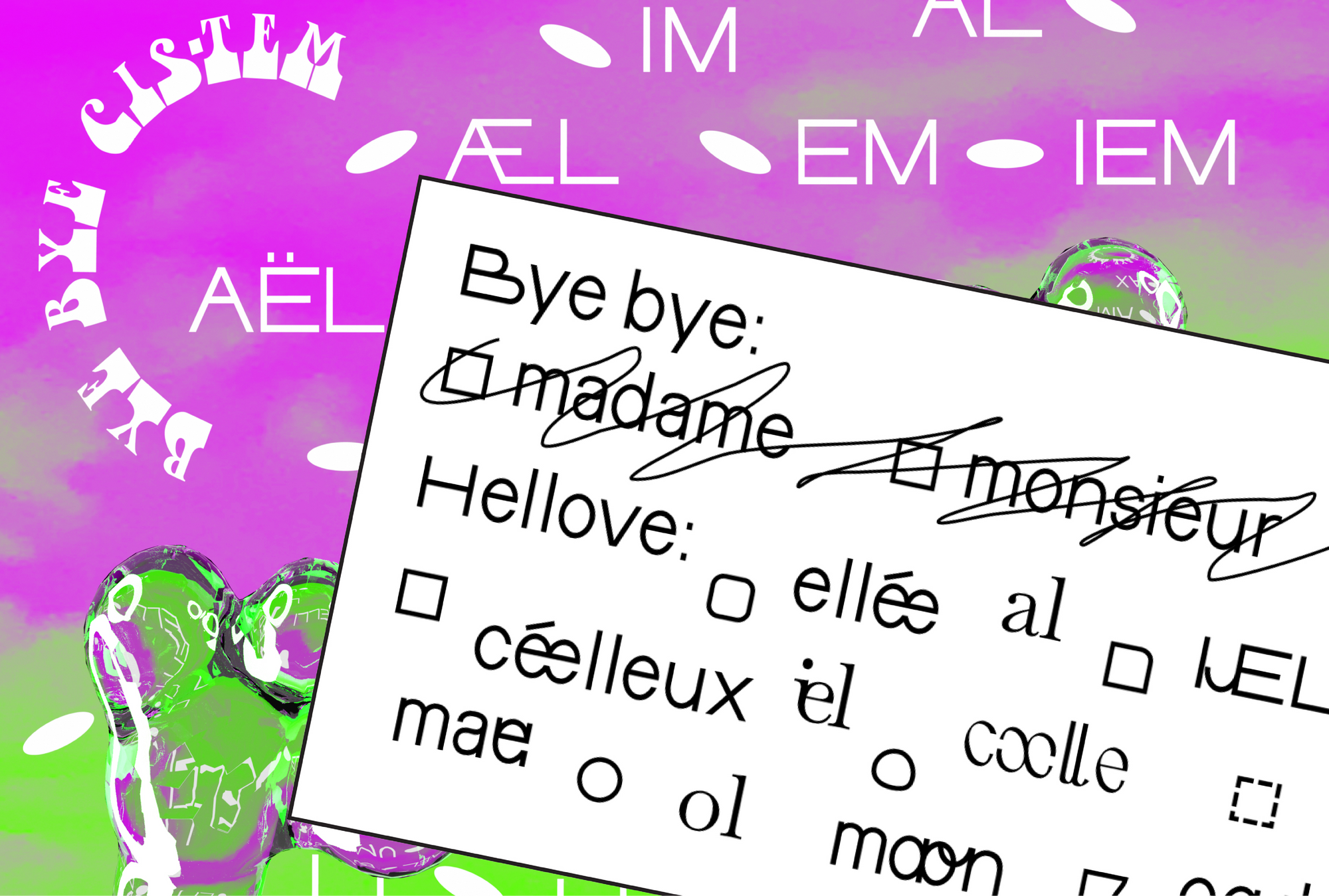

I eventually turned to dreaming as a counter framework for imagined worlds and time, because it returns the agency and power to those oppressed by structures of white supremacy, patriarchy, cishet-normativity, and class systems. My dreams explore the absence or omnipresence of these structures in its metaphysical worlds, refusing to allow a future enforced upon me without autonomy.

Post-techno-orientalist lucidity

Whenever my dream self is being chased by an anonymous attacker, I somehow always know it is a white man. I know he doesn’t actually exist but I still run in fear, trying to find any kind of weapon to fight back because he’s getting closer and closer. To the white man, I also do not exist—I am only the pitiful daughter controlled by archaic Confucian traditions, or the futuristic oriental succubus whose only purpose is to pleasure her oppressor; to him, my identity never lives in the present, but is always forcibly projected either into the past or future. I have often read about the cognitive shift of white people in the U.S.A. when the nationwide perception of Chinese Americans switched from “friendly World War II ally” to “Cold War communist terror.” Then, I witnessed firsthand that same shift when the nationwide perception of all Asians in the United States switched from the docile model minority to the barbaric “kung flu” as a result of Sinophobic capitalist ideologies projected during the Covid-19 pandemic. The already ambiguous Asian American identity was forced into chaotic oscillations through time in order to fit the narratives of primitive degenerate or futuristic superhuman, both impositions designating Asian Americans as “other”—and whatever that is, it isn’t human.

Studies claim that your mind isn’t capable of creating new faces in your dreams, and therefore every lover or killer your subconscious conjures is based off of people you’ve seen, whether it be a close friend or a passing stranger. The irony that an unrealistic dream space is informed by lived experiences is fascinating—it extracts from the past in order to imagine a future to escape the present. In Duty Free Art, Hito Steyerl muses that “history only exists if there is a tomorrow… the future only happens if history doesn’t occupy and invade the present.” I think about the stagnation of the Asian American community and wonder, despite the recent protests against Asian American racism, what are the visions of these movements? The slogan “Stop Asian Hate” rings hollow as East Asian celebrities push for increased policing and media representation, largely ignoring the heterogeneity among the community. Those demands erase the experiences of anyone who isn’t a wealthy cishet East Asian American citizen. I also question, from which histories do they fuel their spirits? What is the future for my people—is it assimilation to whiteness? Is it violent erasure and expulsion from this land? If so, our history of unpaid labor, undocumented immigration, colonization, and leftist solidarity becomes nonexistent. They disappear into the footnotes of textbooks and the whispers of spoken memoirs; into the dreams of silenced revolutionaries.

“We cannot organize if we do not recognize our collective strength. How then do we forge and cultivate a community bound by true solidarity, instead of a fragile desire for acceptance by the white gaze?”

Like the white attacker haunting my dreams, my identity as an Asian American also does not exist. To be Asian in this country is to always live under the jurisdiction of another, and our identities are, to quote Colleen Lye, “a never-ending process of becoming.” Becoming more American, becoming more Asian, becoming more human, becoming more alien. The estrangement and individualization of this nonexistent, conditional identity has separated community members in both time and space, hindering our liberation. We cannot organize if we do not recognize our collective strength.

How then do we forge and cultivate a community bound by true solidarity, instead of a fragile desire for acceptance by the white gaze? Asian American culture is often portrayed as an embrace of Western nationality and political identity while retaining the “desirable” parts of their cultural background—often in the form of commercial commodities and aesthetics. This is especially prevalent in East Asian American communities that thrive on the worship of Sanrio mascots, bubble tea brands, Nintendo consoles, and films like Crazy Rich Asians. Facebook posts flood with comments about strict, conservative Asian parents who gripe about their child’s Western, liberal lifestyle. Childhood stories from mainly wealthy East Asian Americans about being bullied for eating “stinky ethnic” lunches or called “Ling Ling” by white classmates blend into the overplayed narrative of renouncing one’s “Asianness” at a young age to assimilate towards whiteness. These communities dissolve instantly when Asian Americans—especially those who are queer, trans, undocumented, disabled, or sex workers—face violence and materialized discrimination. When six Asian women are murdered by a white supremacist who blatantly admitted to sexualizing and dehumanizing Asian femme bodies, these communities have nothing to offer besides reposted Instagram stories and empty words. Meanwhile, fundraisers and organizations are spearheaded by community-based political coalitions and mutual aid groups. When true solidarity forms through sustained resistance against capitalism, imperialism, and white supremacy, only then can we create a tangible change in response to these violent acts.

It is frequently overlooked that the term “Asian American” was coined by the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) in 1968 as a self-identifier in opposition to racism and Western assimilation. Although the Asian diaspora in the Americas have a deep collective history, the term “Asian American” was largely specific to those living in the United States of America. Rejecting the previous identifier of “Oriental,” the AAPA focused not on ethnic background but rather on an identity encompassing all groups that are marginalized and racialized by white power structures in the U.S.A. Even though now it has been appropriated as a racial identifier, being Asian American is, and always was, inherently and deeply political. It explicitly represents solidarity with all Asians globally, and all communities victimized by U.S. imperialism and exceptionalism.

As Daryl Maeda summarized the words of Chris Iijima in Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America, Asian American identity originated as “a means to organize other Asians for political purposes, to highlight aspects of racism, to escape the hegemony of whites in progressive movements, to support other progressive racial formations, to establish alternative forms of looking at society/history.” Especially in light of recent increased anti-Asian violence, the Asian American community must reaffirm its revolutionary roots and organize against our oppressors.

“Increasing digitalization has allowed us to find kinship beyond the land we inhabit, and forge coalitions with comrades we have never met. [...] In this wealth of resources, we must dream broadly and ambitiously, envisioning a liberated future for all who are oppressed by capitalism and white supremacy.

This is more accessible than ever before—increasing digitalization has allowed us to find kinship beyond the land we inhabit, and forge coalitions with comrades we have never met. It opens access to I Wor Kuen archives and virtual seminars, while providing a variety of open-source software to expand and visualize what tomorrow will look like. In this wealth of resources, we must dream broadly and ambitiously, envisioning a liberated future for all who are oppressed by capitalism and white supremacy.

But this isn’t to say that dreaming is a perfect practice, nor can it be the sole method of resistance in the struggle. We can’t become trapped in the fantastical utopias of our minds and ignore the material conditions of reality. Once we recognize and reject the idea that we are bound to this present time and space, we can recognize that we have the capacity to shape the futures we want to live in. When we inevitably unearth and disseminate our histories of revolution, class consciousness, and racial solidarity, they shouldn’t invade and overrun the present. Instead, those histories should serve as remembrance that we are capable of building our futures—so long as we reject the temporal structures that confine us.

Nina Jun Yuchi (she/her) is a Chinese American designer, writer, and student based in the US East Coast. She recently graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with a BFA in graphic design but returned to get her MA in art and design education. Jun’s practice uses digital design tools to interrogate Asian American political identity through a speculative and community-based lens. She hopes she can develop a pedagogical practice centering dialogue and resistance through design education while maintaining time for their interests such as collecting stickers and watching Naruto. Nina always welcomes conversation and collaboration over Zoom or coffee.

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain workshop.

Title image: A digital illustration of a story in which Nina travelled the universe to find a grain of sand. Text: Excerpts from Ninas dream diary (Credit: Nina Jun Yuchi)

Bibliography:

Crary, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. e-book, Verso, 2013.

Maeda, Daryl. Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America (Critical American Studies). 1st ed., Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Roh, David, et al. Techno-Orientalism. Amsterdam-Netherlands, Netherlands, Amsterdam University Press, 2015.

Steyerl, Hito. Duty Free Art. Amsterdam-Netherlands, Netherlands, Adfo Books, 2017.