Forty pages, photocopied, and stapled together. An action repeated, producing around a dozen copies for a small number of people, who were still unaware that they were about to find just what they needed. It was July 1992, and the first issue of Speed Demon, the first Italian queercore fanzine, was being produced, and was about to be distributed.

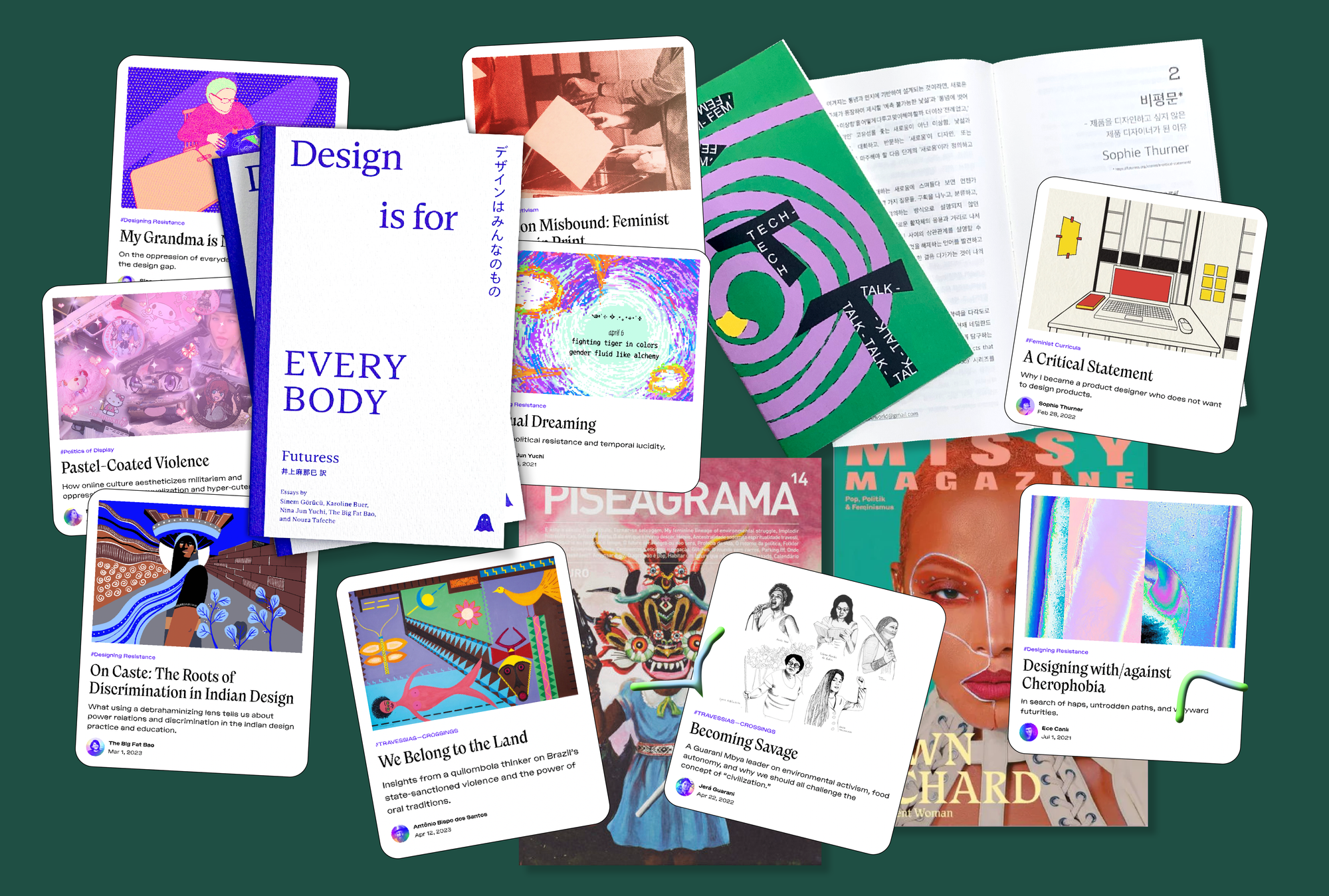

“Fanzines have long been used as a medium of cultural agitation in alternative cultures and subcultures linked to activism.”

This fleeting moment opens up a lasting discussion. About self-produced media, about publishing projects, about communities creating spaces for themselves, and about letting free thought spread without any approval or censorship. Fanzines have long been used as a medium of cultural agitation in alternative cultures and subcultures linked to activism. For many, they became a starting point to create a new space for dialogue and build different kinds of communities. This was also the case for the “queercore” experience, which exploded at the end of the 1980s and soon became an international phenomenon.

Linked to a strong communicative urgency, the queercore community found in the fanzine the most immediate device to translate this kind of need. This movement was one of the most extrovert expressions of punk culture with respect to sex and gender, and within the Italian scene Speed Demon constitutes the main attempt to represent this subculture. Speed Demon was also part of an unprecedented context within the history of self-publishing, namely that of the Milanese fanzines, which even today remains an under-discussed context.

Speed Demon gave a group of previously isolated individuals the chance to become a collectivity, sharing the same interests and the same way of communicating. The fanzine became a “tangible” space where they could connect and find each other. And this space is worth looking back to.

The lead-up to Speed Demon

In the 1990s, between the pages of Italian fanzines from those years, political and artistic activities can be found, activities that sprung up to create and animate new spaces, with young people from all over Italy taking part in these new urban cultural communities. These were the years of the antagonist and artistic activities realised in Bologna by Teatro Polivalente Occupato in mis-appropriated spaces, of the activities of the literary and artistic collective Luther Blissett, and of Forte Prenestino in Rome, an occupied social centre that is still self-organised and active today. These and many other spaces quickly became aggregators that were open to everybody, where communities of different people formed spontaneously around common passions and communicative urgencies. Here, people talked about political struggles and civil rights, feminism and integration, experimental music and performance theatre, and, above all, autonomy.

“Communication became a political act aimed at spreading a new culture through methods that overturned traditional mass media. It was the beginning of a new wave for audio-visual and paper-based experimentation.”

Do-it-yourself culture became a fundamental source of inspiration and approaches to better plan and organise these renewed spaces. Even the aspect of communication was approached from this perspective. Communication became a political act aimed at spreading a new culture through methods that overturned traditional mass media. It was the beginning of a new wave for audio-visual and paper-based experimentation, with radio programmes and autonomous radio stations emerging, streets being plastered with graffiti and posters, and floods of fanzines being sent out, even beyond Italy’s borders.

In that context, the Italian punk scene, already a vibrant force since the end of the 1970s, became the author of a lively collection of fanzines to support its activities and communication needs. The contacts between Italian punks and those of other nations were close and frequent, thanks to the musical and creative production of the Italian scene having been well received both in the international distribution circuits as well as on the stages that had hosted tours of some punk bands.

Speed Demon was born out of this scenario and from the individual effort of at the time 27 year old Flavio Magnani, who was curious to know if there were other people like him out there fighting the norm. The very first issue, published in July 1992, was a cut-and-paste booklet with great visual variety, that brought together international queer-themed contents and advertisements from independent productions from United States and Britain here translated for the Italian audience. There was no mention of the Italian “queercore” scene. Because it didn’t yet exist.

Creating a queercore publishing space

With Speed Demon’s initial issue, Flavio Magnani was talking to a subculture that was struggling to find a physical space for aggregation and that, without having other alternatives, was creating a new one in the free panorama of independent publishing: “In Italy there was no material of this kind. For me, the most important thing was to make material available to the readers to see if anyone else was interested in it,” Flavio tells us.

There was the desire to find a place within the punk scene. But there was also the need to find a medium of expression that could fully embrace a kind of publishing that was highly personal. As a fanzine, there was no compromising of opinions due to editors, publishers, or the rest of the mainstream publishing system. It was a free zone in which everyone could feel safe and represented, far from the most hostile environments of a punk culture that did not hide its prejudice and closure towards the queer cause, as well as towards feminist demands.

“Queercore” as a movement in general was born out of a lack of queer representation within the anti-bourgeois punk culture. It was a catalyst act, an eruptive creation, a politically-needed invention. In 1985, in Toronto, Canada, Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones launched the first issue of the fanzine J.D.s, which was to become the launchpad for the formation of an emerging queercore culture. “In Toronto in the eighties there was a hardcore-punk scene, but there wasn’t an alternative scene for queer kids,” states Bruce LaBruce in the documentary Queercore: how to punk a revolution. “So our strategy was to pretend that Toronto had a full-fledged crazy gay-punk scene already happening.”

This political stance, permeated with anger and creativity, was imitated in other countries. The queercore subculture spread through the pages of the many fanzines it produced and found a turning-point when it was mentioned in the queer-special issue of Maximum Rock'n'Roll, a fundamental zine in the history of punk publishing. From there, the movement quickly spread and became a vibrant, international phenomenon.

“Living in this in-between was the only space for those whose musical tastes were too alternative to be gay and who were too gay to be part of the punk community. Speed Demon turned this gap into an actual room.”

In Italy, the LGBTQ+ community at the time had very few ways of expressing itself and of coming together. The small number of spaces that were openly LGBTQ+ friendly within the most active cities referred to a gay male community, who shared a passion for the happy sound of disco music and the bright colours of the 1990s. For the rest who did not fit into this image, there was nothing left to do but to run back-and-forth between punk gigs at the squat and the disco nights at the gay-friendly club across the street. They were trying to find a way to combine musical interests with social needs. It was frustrating and disorienting, but living in this in-between was the only space for those whose musical tastes were too alternative to be gay and who were too gay to be part of the punk community. Speed Demon turned this gap into an actual room.

The first issue’s dozen copies fell into the right hands. For the second issue, Flavio was no longer alone in organizing and editing Speed Demon. The editorial staff was now joined by the cutting irony of Adriano Di Gaspero, aka Magou, the hardcore punk knowledge of Orlando Furioso, the artistic sensibility of Bartolomeo Migliore, and finally the graphic touch of Angelo “Ango” Visone. Published in November of the same year, the second issue introduced original contents, reviews of other fanzines, and testimonies speaking out about an Italian punk culture hostile to the inclusion of queer struggles.

“I met hundreds of boys and girls (minimum). Punx. Out of all of them, apart from me, only two were openly gay men, and one was a lesbian, who, not feeling up to coming out as such, denied herself and got a ‘front boyfriend,’” wrote Orlando Furioso in that second issue. “So what was the problem? It was that my being gay, and yours and his, was something to be shunned, to be hidden, or, at least, to be mocked.”

“The participatory nature of the Speed Demon editorial project allowed not only to give voice to a community that had until now remained silent, but also ensured that even within this, there was freedom of expression.”

The participatory nature of the Speed Demon editorial project allowed not only to give voice to a community that had until now remained silent, but also ensured that even within this, there was freedom of expression. “Everyone had total independence in writing and composing their own content,” emphasizes Flavio. “For example, Adriano—an all-round expert in the field of music—had a very precise critic’s attitude, which nobody else had in our team. That's why he used to write sharp record reviews for Speed Demon.”

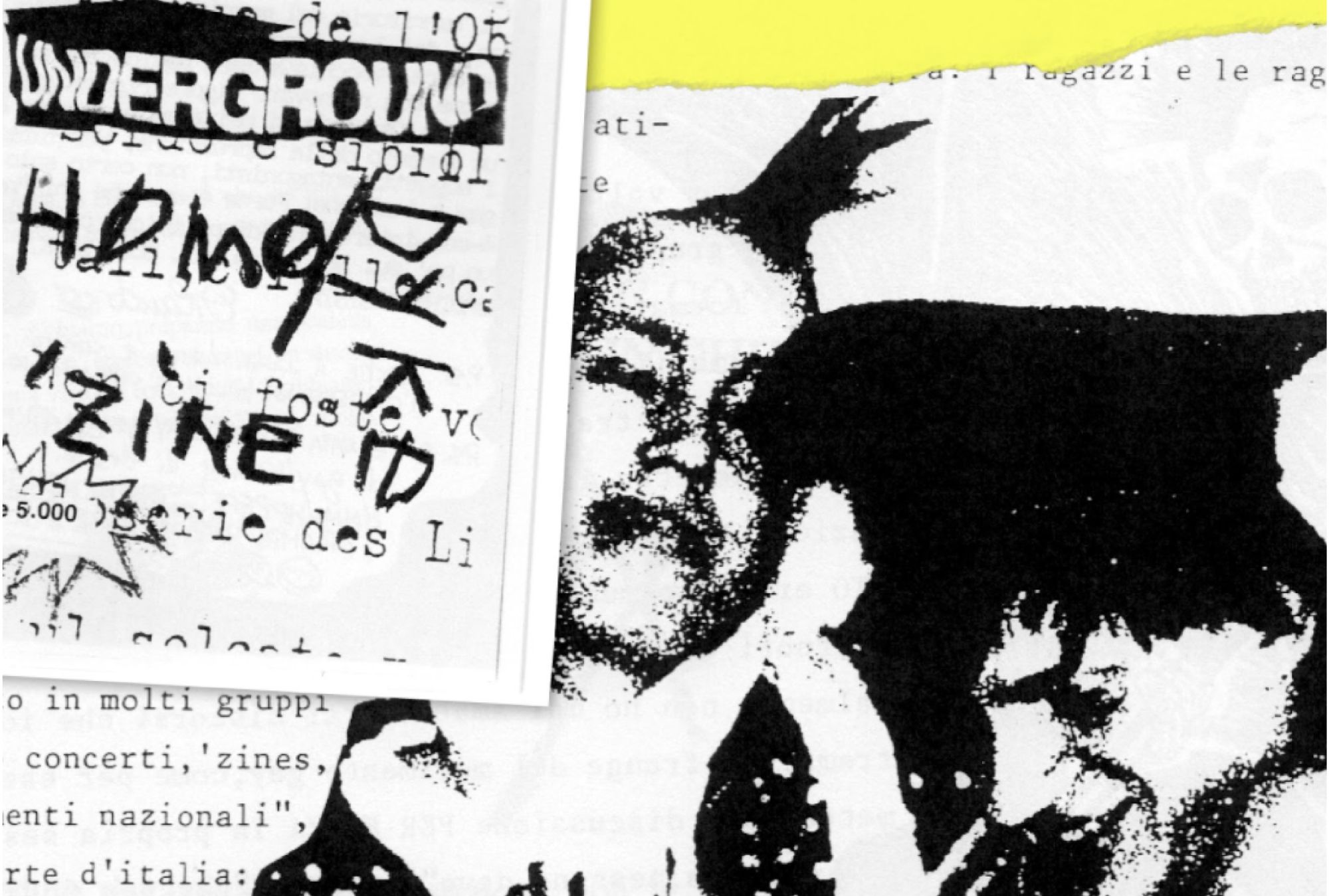

As was the case for other fanzines of those years, the graphic style was shaped by the cut-and-paste technique used and by the materiality produced by the photocopy-machines available. In the case of Speed Demon, in particular, the visual-material layer was an added value to go along with the text and the result was a chaotic and unexpected flow of content. On the pages of Speed Demon, the reader’s attention was mainly oriented towards understanding the text, but it was also drawn into a deciphering of the multitude of images, phrases, symbols, and quotations that burst out of the pages.

“While the first issue was born in a more spontaneous way, later on we had built a conceptual and graphic approach,” explains Magou. “In the other issues a very framed visual research was done, which took up the punk style of those years’ fanzines.” The above described type of graphic language created a break with the look of traditional publications, challenging the reader to observe reality from a different perspective. This kind of graphic design was typical of the punk movement and was of great interest to the editorial staff as it visually expressed what they wanted to say on a cultural level. Breaking with traditions and expectations, wherever one would look.

Spreading through parallel planes

The circuit of underground fanzines, and in particular the one Speed Demon was part of, was a reality that moved on a parallel plane from mainstream media. A circuit with its own editorial staff, readers, events, and distribution network. Speed Demon’s readership grew thanks to the activity of local distributors and mail-order-systems—a wild and frenetic machine made up of dedicated fans of the genre who cultivated contacts with other national and international communities. Thanks to the “distros,” as they were often called, the dissemination of music, literature, and publications far from canonical productions could finally find a wider scope.

“There were a few bookshops in the big cities, which left space for fanzines and self-productions—at least those considered ‘the best ones.’ However, the whole antagonist, punk or countercultural circuit has traditionally practiced postal distribution,” Giulia Vallicelli, an active figure in the riot grrrl scene of those years, recounts. “Before the spread of the internet, self-publishing could only be found at specific events where tables were set up with information material, printed on paper, of course.”

In Giulia Vallicelli Speed Demon found its main distributor for Italy and abroad. Compared to the other distros in the area, hers was the first Italian punk distribution that had a strong focus on feminist and queer self-productions. It’s no coincidence that these two movements are often associated with each other. One cannot talk about queercore without also mentioning the punk-feminist riot grrrl movement, which exploded in 1991 in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and spread through fanzines in support of all the womxn of the alternative scene who, similar to the LGBTQ+ community, suffered from the hetero-cis-male machismo attitude of both the punk movement and of society in general. “As soon as I read about Speed Demon on a flyer, we wrote to each other and got to know each other better,” says Giulia, recalling how she chose to add Speed Demon to her distribution catalogue. “Afterwards I tried to strongly promote the fanzine both on my mailorder catalog and at shows.”

The intricate and dense flow of reviews, interviews, articles, and opinions ranged from politics to the arts and music, satisfying a growing community that became soon more solid and numerous. Issue after issue, the zine, published on an average annual basis, gathered a diverse and generally indie readership. In this sense, the constant and inclusive search for new contributors, the attention to what was going on in society, politics, and underground culture, the dialogue with its readers, together with its specific positionality within the underground movement made it a unique project—heterogeneous and constantly evolving.

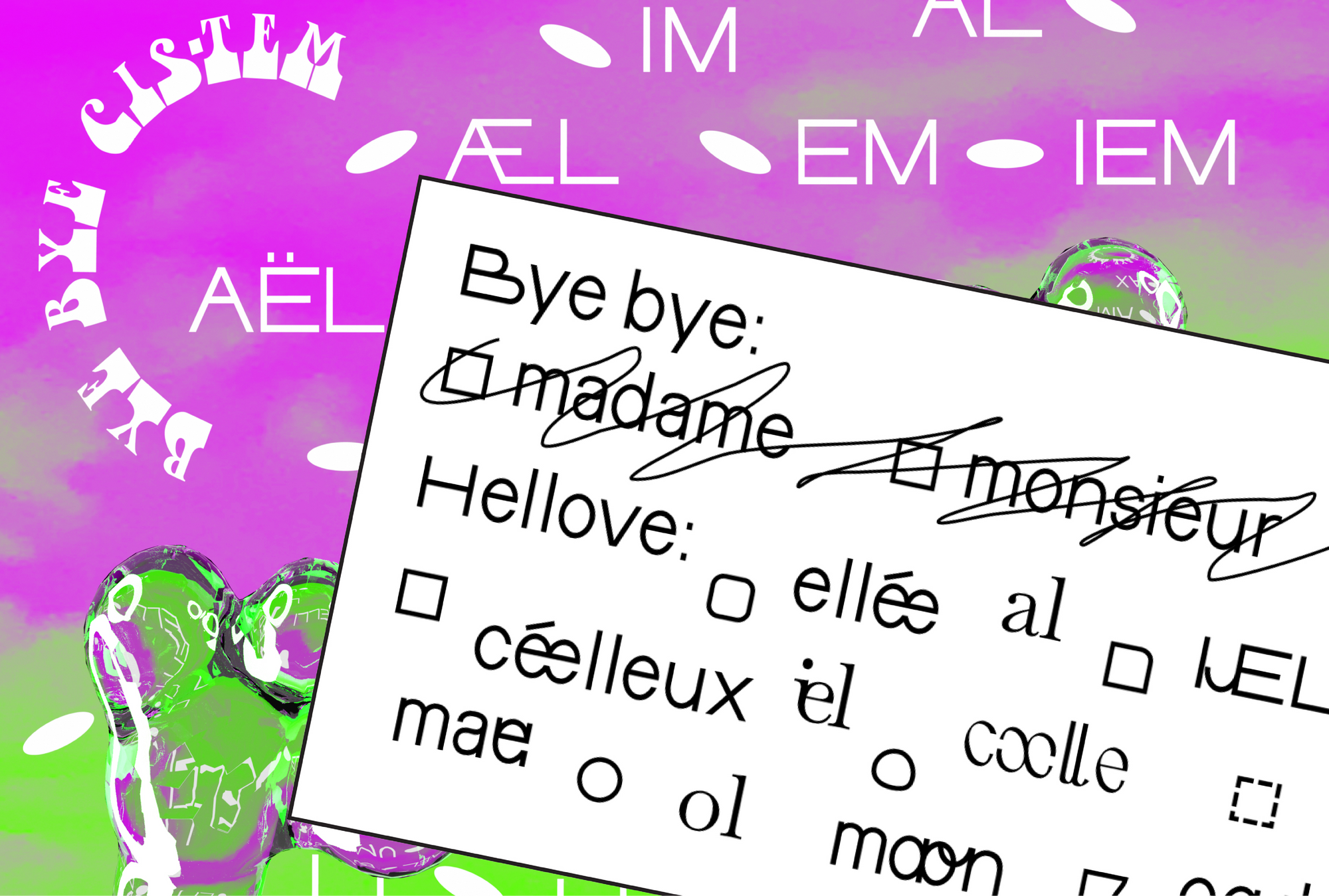

Evidence of a certain openness of vision can, for instance, be seen in the subtitle of the zine. While the first issues are addressed to a “homo”—as in homosexual male—audience, from the fourth issue onwards, the words “homo-dyke zine” were inserted, until the final statement, starting on the seventh issue, which referred to a “queer and underground” audience. In that same issue No. 7, in an opening message written by a contributor called Tina, girls were invited to work within the zine’s editorial staff in order to offer a more consistent focus on dyke culture and feminist demands. As Tina wrote: “A gay/lesbian fanzine made by males only? That sucks!”

“In addition to print media, the Speed Demon community also met through other channels. First and foremost through its queer nights: events organised by the editorial staff to enjoy, after reading, everything that being queer implied.”

In addition to print media, the Speed Demon community also met through other channels. First and foremost through its queer nights: events organised by the editorial staff to enjoy, after reading, everything that being queer implied. “There was a need to get to know each other in person and to share experiences and experiences,” Flavio recalls.

In those years, evenings of this kind were a novelty even for people who frequented underground environments. As Flavio explains, “In Milan, there were many social centres, but there was no gay component inside them. Even though they were very political, the issue of sexuality had not yet entered the spectrum of topics covered.”

At the S.Q.O.T.T., a community center located on the fourth floor of an old-fashion Milanese building, the issue was completely different: “There, a lot of importance was given to new heterogeneous forms of artistic expressions and unconventional subcultures,” Flavio explains. “I took part in the collective that ran the space and had the opportunity to propose themed evenings that did not exist in Milan at the time.” The spin-off had contributed to new forms of engagement among the alternative communities of the prolific Milanese cultural scene, giving them a physical space to better interact. Book presentations, performances, and drag shows brought a new message to a context where these types of events had previously never set foot in.

In this community center, any new presence was welcome. “It was a mixed audience, not confined to the punk scene,” says Magou. “At a certain point, there was such a heterogeneity that it attracted different kinds of artistic or even musical experiences. So you could find the punk group next to the hip-hop group or the singer-songwriter. It was an organically grown community and there were no preconceptions about it."

Internet killed the Speed Demon

In the beginning of the 2000s, as Internet access widened and web 2.0 technology spread, the digital shift affected many youth cultures and underground scenes. The internet was like a new virtual and stimulating harbor, where users from all over the world could dock to get to know each other, exchange information, and develop communities in a spontaneous and creative way.

The internet page GeoCities was one of the most significant phenomena in this context. Active since 1994 as a web-hosting platform, GeoCities allowed users from across the globe to communicate their passions and interests through the creation of web pages which were part of virtual cities. Cyber-space thus compensated for the criticalities and geographical difficulties of the real world, and provided a new scenario made up of virtual constructions to create new hubs for subcultural niches. Among the cyber-constructions of Geocities were West Hollywood, a digital space for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender users, or Sunset Strip, a place for fans of rock, punk, grunge, and the club scene. The idea of connecting distant people in a free, virtual, and friendly space met the communication and gathering needs of the LGBTQ+ community. The concept of GeoCities, as its founder David Bohnett explains in an episode of the 99% Invisible podcast, is derived from a personal, first-hand experience: “A lot comes from my own experience as a gay man, coming out, meeting other gays and lesbian people, and understanding the power of meeting others of your own identity.”

The cyber-revolution of web 2.0 shaped new virtual identities for its users, transcending the social limitations of life in the flesh. With the advent of new computer languages, the world wide web soon also hosted the first forms of social networking, themselves rapidly transforming. Within the span of only a few years, the early irc chats, message boards, and newsgroups were overtaken by new blogging services such as Wordpress, and virtual macro-communities such as myspace.

In a world where information now traveled around the globe at breakneck speed, the work of creating printed zines was becoming increasingly tiring and obsolete. For Speed Demon, the decline of print was gradual, but it was inevitably linked to the new rhythms dictated by the instantaneous flow of the web. As Flavio remembers this turn towards the digital: “The effort invested in researching material for Speed Demon was now more or less useless.” The production of unreleased content and interviews took a lot of time, as did the planning and distribution of the editions. What is more, the promotion and distribution of the new issues still followed traditional methods, not taking advantage of the opportunities digital communication also provided, which were still mostly unexplored at the time.

Internet culture hit Speed Demon in different ways. Most visibly, it also affected the visual aspects of the zine, which were being revolutionized by new artists and designers such as Dafne Boggeri, who designed the covers of the last three issues. After twelve years of activity, Speed Demon’s initial project was finally toppled by the new digital frontiers of the contemporary world, slowly rendering a once very necessary space seemingly obsolete and ever more difficult to keep up. In 2007/2008, Speed Demon published its fourteenth and last issue.

“In instant-messaging services and digital mailboxes the new generation of readers found a more functional alternative to the physical mail-out and letter exchanges on which the community of various international distros was based.”

In the colophon of the last edition, a myspace link refers to a new virtual space where Speed Demon tentatively tried to continue the editorial experience, but it was not a successful attempt. “Not being millennials,” Flavio reflects, “we didn’t even opt for an online fanzine because we didn’t have the technical skills. We came up with the idea of turning the paper fanzine into a website but it was not our thing.” In instant-messaging services and digital mailboxes the new generation of readers found a more functional alternative to the physical mail-out and letter exchanges on which the community of various international distros was based. Paper catalogues gave way to digital ones, attached to digital newsletters, electronically sent out through the networks of the various distributions.

While the print issues decimated, the real-life meetings in Milan multiplied. The queer nights in the social spaces continued. Apart from that, Flavio Magnani started Pinkitchen, community dinners supported by other vegetarian chefs, where Giulia also enjoyed cooking for the community. And at the Cox18 community center, Ango and other contributors of the zine promoted Pornflakes, a series of performance-dance evenings.

Years later, even these spaces have disappeared. And yet, the project is far from forgotten. “After the very last issue, Speed Demon as a concept remained and it still survives. Since we stopped, there has also been a process of rediscovery of our project,” explains Magou. “This is not the first time we had the opportunity to talk about our experience with Speed Demon, which for us was the expression of our lives and our feelings.” Today, a strong and surging wave of awareness around LGBTQ+ discourse has facilitated a renewed interest in projects such as Speed Demon. Those who have once been the commenters and creators of queer culture, have now themselves become the objects of study.

Queer remembrance in a digital age

All the original issues of Speed Demon are today kept and made available at Compulsive Archive, a Milanese archive for lesser known punk publications founded by Giulia Vallicelli, giving particular attention to riot grrrl and queercore fanzines. “Compulsive was the best place to keep our project interesting and above all continue researching its meanings,” Flavio comments. “Otherwise everything would have remained in our wardrobes without memory.”

In her archive, Giulia, an important reference person for queer feminist-themed distribution in Italy, now collects fanzines, records and materials related to her activity in the punk scene. “Compulsive was born in continuity with the experience and memory of the years in which I was most active, because it is a personal archive,” explains Giulia. “But for me it is also a political gesture of restitution of certain communal experiences outside the institutional archives, which have a dimension of dignity and importance.” Compulsive comes with the idea of enhancing the independent production born on paper by putting it in dialogue with the new generations and the digital environment.

This type of independent archival practice takes on even more significance when considering the issue of historicization. “I find that the off-voices of fanzines or those of young people—in the case of the punk scene—are very important precisely in order to integrate them into official historiography,” Giulia explains. “In Italy, institutions tend to focus more on historical and artistic heritage, to the detriment of the more social aspects of culture.”

In addition to being direct political and cultural testimonies, these materials, born on paper, were mostly used as a means of identification and socialisation before the digital social network, as we know it today, existed. “The fanzines created before the advent of social networks have characteristics that today would be at risk from the point of view of privacy,” says Giulia, “as they contained addresses in plain text, strong opinions, and details of private facts and sexual orientation.” These are very intimate aspects that, in print, were able to be narrated in an explicit manner, as Giulia explains, “because they were productions on paper, spread only within their own bubble, even if communicating with others.” What would exposing such contents to search engines and a digital readerships mean nowadays? The medium of the printed fanzine had given even the most reserved and least exposed people the opportunity to have their say, and share intimate details relating to sexual orientation and gender identity. The digitisation and uncontrolled dissemination of such content would mean exposing it to an infinitely wider community than the one for which it was intended—and not necessarily a safer or friendlier one.

It is therefore no coincidence that the fanzines produced today are very different from those of a few years ago: in content, language, and style. The gradual abandonment of analogue media together with the spread of the internet has updated and profoundly changed the function of fanzines. “Today’s fanzines hardly have any content. They are now very graphic, stylistic, and focus on images,” Flavio observes. “The original fanzines were full of texts, news, and opinions because that was the content we couldn’t find anywhere else. Now, that kind of information would already be old by the time the fanzine is printed.”

While in some cases the medium of the fanzine may lose its informative and popular character, in many other projects it comes closer and closer to a sensibility typical of artistic circles and visual communication. This new type of approach, which has also partly affected the thinking around vintage fanzines, raises a number of questions regarding their management as artefacts, calling into question their very nature. “From the point of view of conservation, I can agree with the practice of putting original fanzines in a glass case, displaying them in an exhibition or in an institutional archive,” says Giulia. “But, given the social nature of the medium, enhancing them only in this way, seems like a loss to me.”

The project by Flavio, Adriano, and all the other Speed Demon contributors is a small miracle in the history of zines. Few other publications can boast such an enduring production span, despite only a small number of copies having being printed per each edition. Flipping through the pages of Speed Demon allows us to grasp more intimate and particular aspects about the past that help restore a part of history that is still underexplored today. To study past fanzines such as Speed Demon, allows us to understand the main elements that led to the development of a medium that continues to exist today.

Looking at bygone fanzines is a way to reconstruct and remember where we started from. Before we arrived at glossy publications. Before fanzines became nostalgic products that we are almost afraid to leaf through. If, on the one hand, “the act of making a fanzine is linked to the discourse of dissemination something as widely as possible, even when dealing with obscure and niche topics,” as Magou puts it, then on the other hand, the true sense and form of this kind of device today is no longer bound to the printed page but is hosted elsewhere.

It is in the various forms of virtual community that the legacy of fanzines lives on. In their creative ways of dealing with the same communicative urgency. In their need to keep pace with hyper-rapidly evolving technologies. In their reflection of a constantly changing social context. Whether physical, paper, or digital spaces, the urgency is always the same: to be a community.

Vittoria Pugliese (she/her) is a furniture designer based in Milan. Her design approach is based on the observation of the relationships between objects and people and how they can be conveyed.

Elio Raimondi (he/him) is an italian graphic designer. His practice explores visual languages and

institutional/non institutional models in order to interpret contemporary culture.

They are both part of Designer Of What, a collective formed by six designers who uses newsletter

as an effective medium to spread ethical and critical design cultures with the italian audience.

This text was produced as part of the Troublemakers Class of 2020 workshop.