Tomorrow is the last day to see Errata. Held in the Gabinete Gráfico, Museu da Cidade in Porto, the genesis of this exhibition started with a reflection on my own design education and career. More specifically, by realizing the sheer lack of female figures in all aspects of my design practice. From the bosses at studios where I worked, to the male professors teaching a history of male designers, women seemed conspicuously absent from design. After encountering the work of a number of significant Portuguese women designers, whose histories were missing from mainstream design discourse, this absence seemed ever more egregious. Determined to raise awareness of these women’s work, and to better understand the reasons behind its omission from design history, I began the research project which would become Errata. Together with my friend and colleague, Olinda Martins, we applied for funding to stage an exhibition highlighting the work of women designers in Portugal. A year later, the Errata is here. The text which follows is an edited version of our curatorial statement.

“Yet here we are, asking again the same questions that shouldn’t have to be asked: why are women absent in design history?”

Before we begin, let us first say that this exhibition is absurd. It is ridiculous that “women” is seen as a sufficiently specific and comprehensive categorization on which to hang an exhibition and to unite the works of varied individuals from different times and backgrounds. Yet here we are, asking again the same questions that shouldn’t have to be asked: Why are women absent in design history? Why have women who were notable during their careers been forgotten? What mechanisms have permitted these omissions?

When the Errata project started, we gave ourselves the task of organizing an exhibition about women in graphic design that had worked in Portugal during the 20th century. These geographical and temporal boundaries were not set with any particular nationalist or historical vision in mind. It’s not the intention of this exhibition to find a so-called “Portuguese design,” nor to redefine the history of graphic design in the 20th century; they were just necessary boundaries we chose to help keep us focused. The selection of women wasn’t predetermined either, but emerged as the research developed.

“It was troubling to recognize the lack of female role models throughout our education—we were taught by a majority of male teachers, who were educating us mostly about a Euro-centric design history consisting of overwhelmingly white, Western, male design stars.”

The motivation for Errata came from a reflection on design criticism and our own paths in design. It was troubling to recognize the lack of female role models throughout our education—we were taught by a majority of male teachers, who were educating us mostly about a Euro-centric design history consisting of overwhelmingly white, Western, male design stars. Also, at a professional level, we were always working in environments where our bosses were male. These realizations suggested systemic problems from beginning to end.

In Portugal, the literature on graphic design history is slowly improving. In the last ten years, two widely-distributed monographic collections were published, Colecção D and Colecção Designers, and Colecção Design Português, a set of books tracing the history of design in Portugal from 1890–2015. However, despite this increase in design history publishing, across these collections very few women are mentioned, with only two women—Ana Salazar, fashion designer; and Lizá Ramalho, one half of the duo R2—given any focus.

“The fact that so many women could come to our attention through simple research methods suggests that [...] the process of documenting and remembering is inherently misogynistic.”

This absence of documentation led us to initially underestimate the scope of the exhibition. Our first idea had been to focus on the work of three or four designers, but as our research proceeded, more names kept cropping up. The fact that so many women came to our attention through simple research methods suggests that the issue is not exactly a lack of women in the profession, but a process of documenting and remembering that is inherently misogynistic.

Our approach had to be different. Rather than looking for textbooks and monographs, we instead turned to people. We sought out the few names we found in old publications or awards lists, and historians and thinkers with some knowledge of the subject, and spoke to the women involved. From these first conversations, more and more women came to our attention—in many cases as friends who had also studied design, as female colleagues, as teachers, as partners; in other cases, dead ends, or twisted paths we were unable to follow. Gradually, by word of mouth and the remembrances and half-remembrances of our initial sample, the list of women grew.

“How and by whom design work is documented, archived, and exhibited is inherently biased— therefore no possible method can be entirely neutral.”

Though necessary, identifying forgotten practitioners and adding their names to history is not enough if that mode of history is inherently problematic. Determined not to perpetuate the same hero- and artifact-led narrative commonplace in graphic design history, we faced a challenge while preparing the exhibition. How could the work of these women be shown without merely becoming an appendix to the canon?

This question has been in our minds throughout this process. We were conscious that how and by whom design work is documented, archived, and exhibited is inherently biased— therefore no possible method can be entirely neutral. With that in mind, we considered numerous curatorial approaches to try to answer it as best as we could: from presenting all work chronologically (rejected for feeling too much like a standard linear narrative of design history); to grouping by type of object (rejected for being too artifact-centric); to stripping out any mode of formal organization altogether, ordering objects by a kind of free-association and providing various “maps” to plot different routes through the exhibition (ultimately rejected for its complexity).

While there was merit in a number of the approaches we rejected—an intent to flatten hierarchies and blur distinctions between practitioners, objects and biographies—we came to the conclusion that we were at risk of obfuscating the women and their work behind a conceptual framework. We eventually decided to return to the original aim of Errata: to raise awareness of women’s contributions that have been overlooked, ignored and forgotten, and in doing so reveal the mechanisms still present that consent to these omissions. We can’t understand these mechanisms without looking at the context in which these women lived and worked. Therefore, it is important to reveal the histories behind these women, to impart their names into history, while acknowledging others that worked in collaboration with them, and to consider the context in which the work was created, with all its prejudices and problems.

There are, of course, many mechanisms which result in the oppression and exclusion of women from history. In presenting this exhibition, we have settled on three broad terms—Home, Narrative, and Institution—to frame some of these mechanisms which have a direct effect both on how women work, and how that work is seen by design history.

HOME explores the persistence of patriarchal systems, in which the norms and structures of both the design world and broader social landscape restrict women’s opportunities and define the ways in which their contributions are interpreted and recorded. In the first half of the 20th century, before the formalization of “design” as a profession, artists were often commissioned to—amongst other things—illustrate and create the covers for books. This practice, called “graphic arts”, was common to all artists, but female artists were by a large part being commissioned to work on educational books for women and for children, which in turn were often written by women as well. Even though male artists were also working on books for children, commissioning women mainly for this kind of work was a reflection on the limited role society deemed appropriate for women, often as mothers and wives, bound to a domestic life. The acceptable norms for women, and the conformity to or transgression of these norms, become the defining characteristic of the work. Whatever its subject, voice, or context, if a piece of work was created by a woman, it will always be regarded and assessed (whether by contemporary society or by the historical gaze) in terms of the gender of its creator.

NARRATIVE highlights how design history’s focus on the heroic narrative of the (usually male) individual and their artifacts comes at the expense of more nuanced stories. The formalization of “graphic design” as a discrete profession in the second half of the century would have direct consequences for how history records design. Its addition to the establishment (both educationally and professionally) paved the way for the hero-led story we’ve become accustomed to, which constructs a clear progression of a designer that follows a path of apprentice to a (male) master, learn the trade, become a boss (and name the practice after yourself), then eventually become the master to new apprentices. By establishing a profession with specific skills and boundaries, the focus of history was narrowed, resulting in the exclusion of women whose practice was more multidisciplinary. But design is most often a varied, collaborative, and collective effort. Those women—who have worked not always under their own name, but in various collaborations with different collaborators; sometimes within studios, sometimes independently—present a difficulty for conventional design history. To follow their work is to look for many names in many places, often without clearly delineated authorship. Design history wants to tell us simple stories, but the reality of design, particularly for women designers, is far more complex.

INSTITUTION considers the work of women within publications, publishers, and other institutions, arguing against the predominant idea that success can be measured only by an identifiable authorial voice or a wide and varied portfolio of different projects. This idea excludes an enormous number of designers from the record. Those who work for a single publication for many years, or whose work doesn’t follow the established binary designer/client relationship because the designer works in-house, are excluded. History’s search for a signature in a designer’s work has determined that only the designer whose work is recognizable, repeating similar styles and visual languages across different projects for different clients, should be considered noteworthy. Those whose approach to design—either through personal choice or through the attendant requirements of working within an institution—is more chameleonic or conciliatory to different projects or clients’ needs, create a collection of work that isn’t easily identifiable as of one designer, but rather the work of many combined voices. The three groupings we discuss here are neither discrete, absolute, nor comprehensive—much of the work we put in one group could easily have been placed in another—and there are many other groupings (or ungroupings) which we could have used instead. Rather than try to construct perfect groupings (and such groupings would always be constructions), we instead choose to embrace and promote the imperfection and uncertainty inherent in the act of curation. As history’s methods and approaches are in constant need of revision, so is Errata. This is an ongoing research project, and this exhibition is one of the first and necessary steps, but it is not an end point to this investigation. It wouldn’t have been possible to understand history’s methods of erasure without having met and documented these women’s work. What we have learned from this step has confirmed some of the suspicions which fuelled the start of this project, but also informed us about wrong assumptions and opened our minds to other paths to pursue.

“We asked: where are the women designers? But so many other questions are in need of answering: where then, are the BIPOC, the queer, the collective, the reclusive, the untrained, and the unnamed designers?”

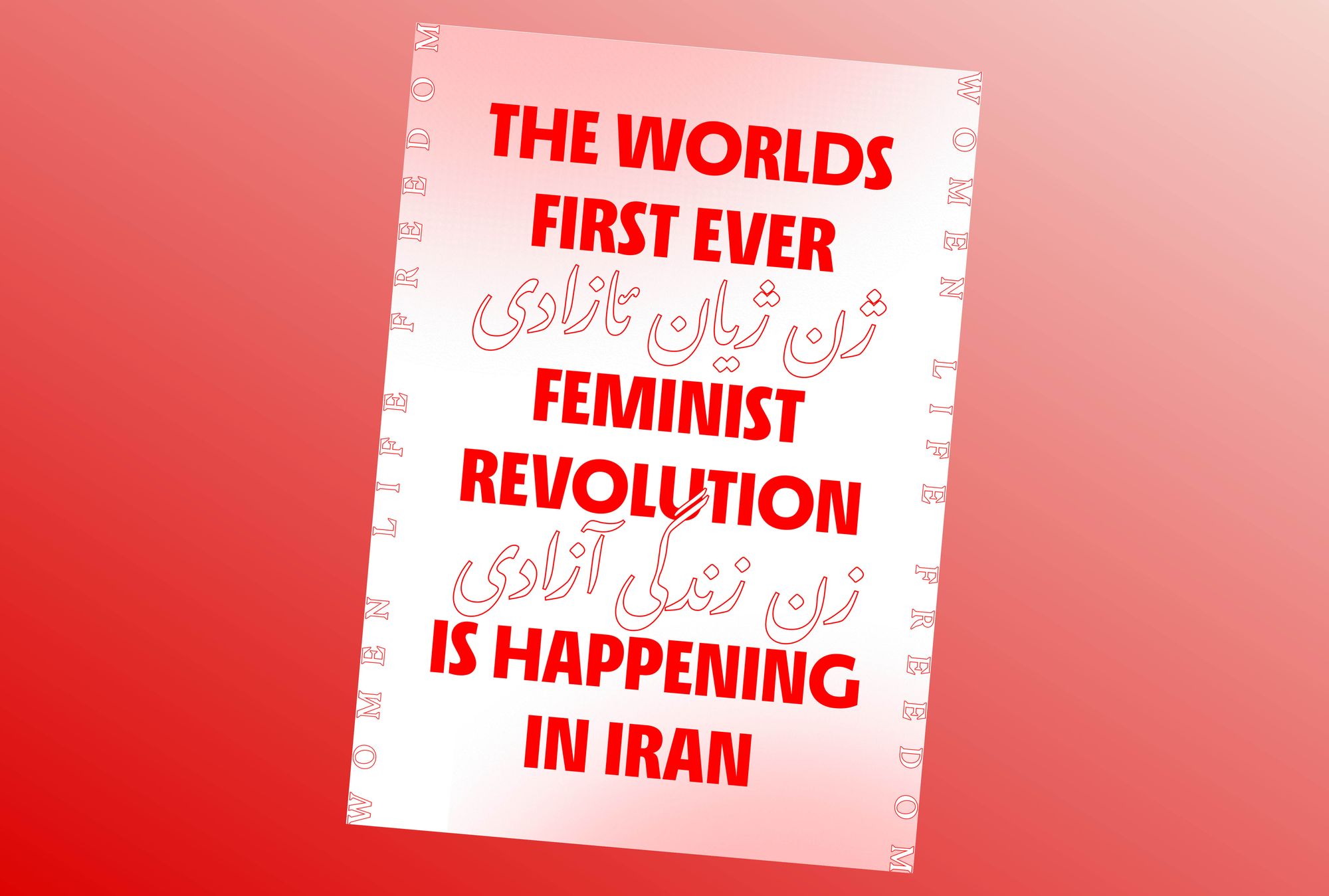

We called this project Errata—a list of corrected errors appended to a publication—not just because we hope the work exhibited here can act as “errata” to current design history, but also because errors and revisions are central to the production of history. Rather than be seen as “extras” to an otherwise complete story, they should instead be integral to the history itself, offering alternative stories and relevant information, whether it fits a narrative or not. Therefore, in addition to this catalogue, a collection of Errata sheets can be gathered in the exhibition, where we have written down our interpretations of the lives and work of the sixteen women presented in the show, as well as other relevant information about the Errata project.

As we fight the imposition of neat categories to write history, we have also made the decision to limit this exhibition to the work of women. But pulling at any one thread only reveals how many other threads are bound up in the same knotted mess. We asked: where are the women designers? But so many other questions are in need of answering: where then, are the BIPOC, the queer, the collective, the reclusive, the untrained, and the unnamed designers?

We are acutely aware that in putting together this exhibition, we have made many significant omissions of our own. No Black women are featured in this exhibition. The selection of work is very much Lisbon and Porto-centric. The women featured come from backgrounds which enabled them to pursue careers in the arts with little resistance. The work featured consists primarily of classic “design objects”—books, posters, magazines—produced for commercial clients, and it excludes works of more vernacular and ephemeral production. These omissions are unintentional and easy to “explain away”, but they remain extremely problematic, and rather than brush them under the carpet, we want highlight them here—both as an illustration of how easy it is for such omissions to become ossified when events become historical record; but also as an incitement, to ourselves and to others, to continue the necessary research and address these omissions in future realizations of this project.

And so, we present Errata; not by any means a comprehensive catalogue of all the women graphic designers active in Portugal, but rather an attempt to identify some of the figures and groups who have been ignored by the canon, document their practice and context, and in so doing, explore the wider reasons their work has been overlooked, an understanding of which will help to ensure the women working in design today and in the future are not similarly forgotten.

Isabel Duarte (she/her) is a Portuguese graphic designer interested in the intersection between design history and feminism.

We invite you to listen to the Errata podcast that brings the discussion on women’s visibility in design history to the present by discussing the subject with historians, curators and contemporary practitioners. The podcast also functions as a research tool and audio archive of the conversations we had with, or about, some of the women presented in the exhibition.