A crowded, sprawling urban setting, bustling with the comings and goings of people, vehicles, animals; everyday life blooming along narrow streets; skies flushed with an unnatural mustard glow. Suddenly, an explosion.

Two black cars in the lonely, rocky landscape; the dry soil betrays their paths, meeting from opposite directions, across borders. Guns cocked, the two men exchange beige paper bags under a punishing yellow sun. A shot echoes through the desert.

Bullets fly across the air as he crouches behind a crumbling wall. Beads of sweat frame his forehead and roll down his neck in the grueling heat, staining his khaki uniform. With calculated movements, he swings his gun over the edge, rears his head, locks his eyes on the target. One precise shot, and death arrives to a faceless enemy.

Scenes repeated a thousand times, awash in a range of ochre, mustard, and khaki tones. An execution in the Mexican desert in Steven Soderbergh’s 2000 movie Traffic; the tale of an ill-fated U.S. military operation in war-torn Somalia in Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down, from 2001; drug deals in Mexico in the 2008 series Breaking Bad; terrorist attacks in the 2011 series Homeland; car chases in Bangladesh in the 2020 movie Extraction. Images and stories tied together by the aggressive use of yellow filters: a visual narrative that, particularly after the turn of the century, has been increasingly present in Western cinematic productions to depict locations in the Global South.

“Across screens, formats, and genres, yellow hues become a shorthand for underdevelopment, tension, danger, and primitiveness—threats not only to the white heroes trying to save us from ourselves, but to the very core of Western lifestyle and values.”

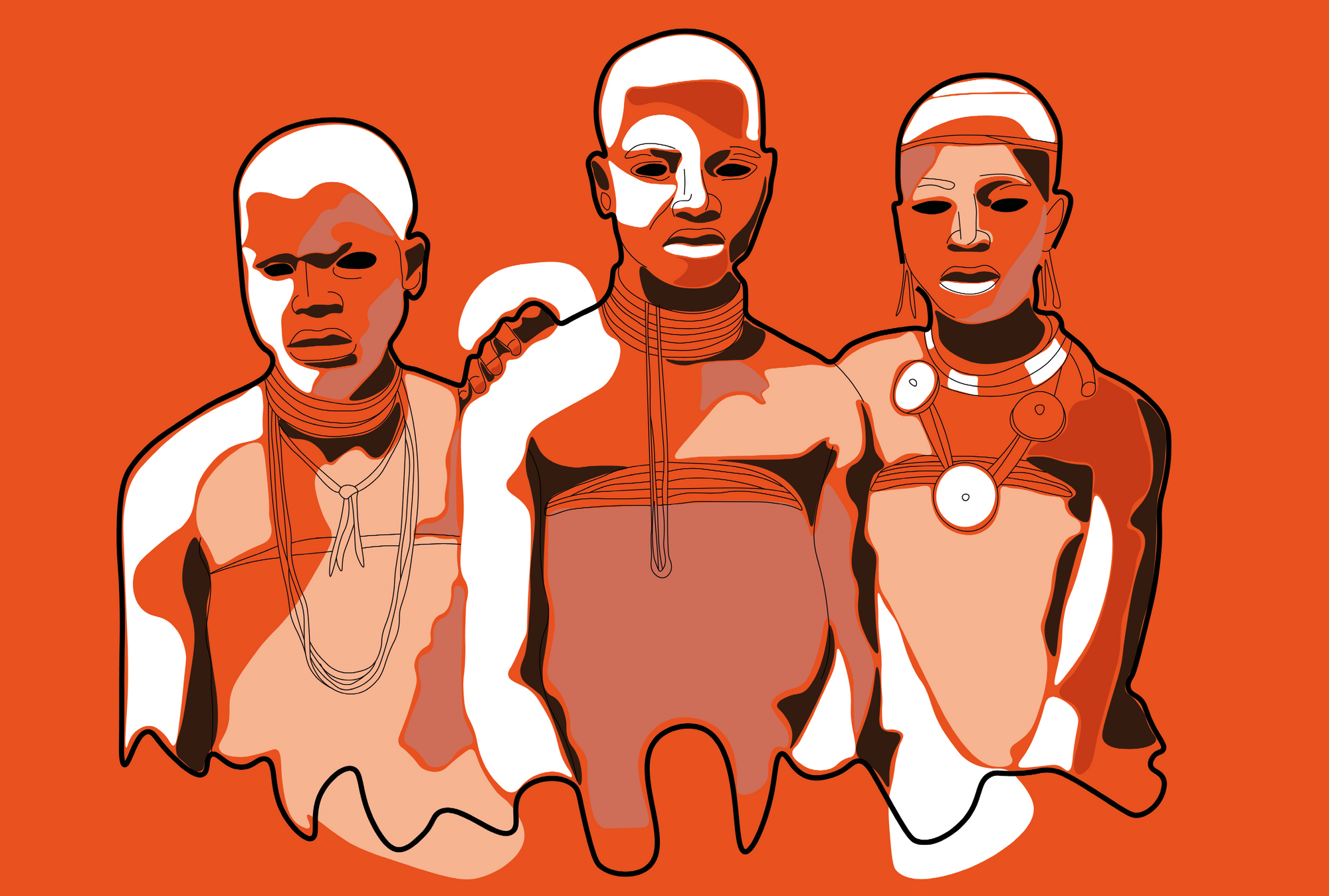

Across screens, formats, and genres, yellow hues become a shorthand for underdevelopment, tension, danger, and primitiveness—threats not only to the white heroes trying to save us from ourselves, but to the very core of Western lifestyle and values. Dirt yellow, jaundiced yellow: an implication of impurity, grime, disease, heat, and pollution; often contrasted with scenes of clean Western locations or contexts, set in contrasting, cool, blue tones. Underscoring these depictions is the perceived right to look, represent, reimagine—a gaze intent on claiming ownership of an other. An ownership that extends beyond the image, too, presenting itself as an inherent right to seize and occupy lands, bodies, languages, cultures, spiritualities; a right to determine who and what belongs, and who and what does not.

Should it come as such a surprise that, in the new geopolitical context ushered by the 9/11 attacks, and the subsequent imperial wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, dirty yellow hues seem to become rapidly more prominent in the visual representations of the Middle East? Should it come as a surprise that, with the creation of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2003 during the Bush administration, and the subsequent increase in the incarceration of migrants during the Obama and Trump presidencies, depictions of Latin America take on a jaundiced yellow shade, as if to warn against the danger of unrest and disease knocking at the Southern borders of the United States? Colonial violence arrives clad in military khakis under the pretext of freedom—drab, desaturated yellows, robbed of all life and vibrancy.

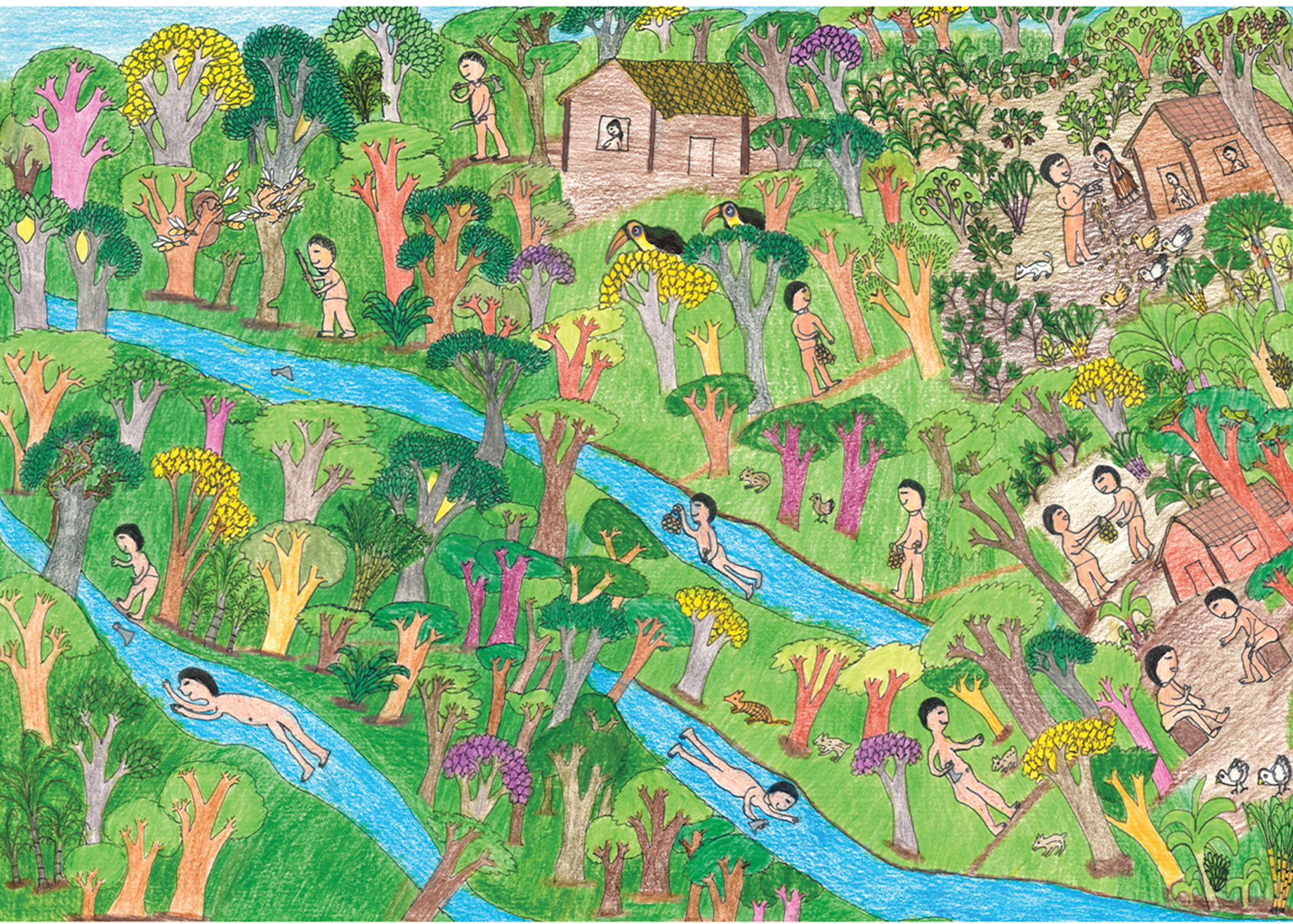

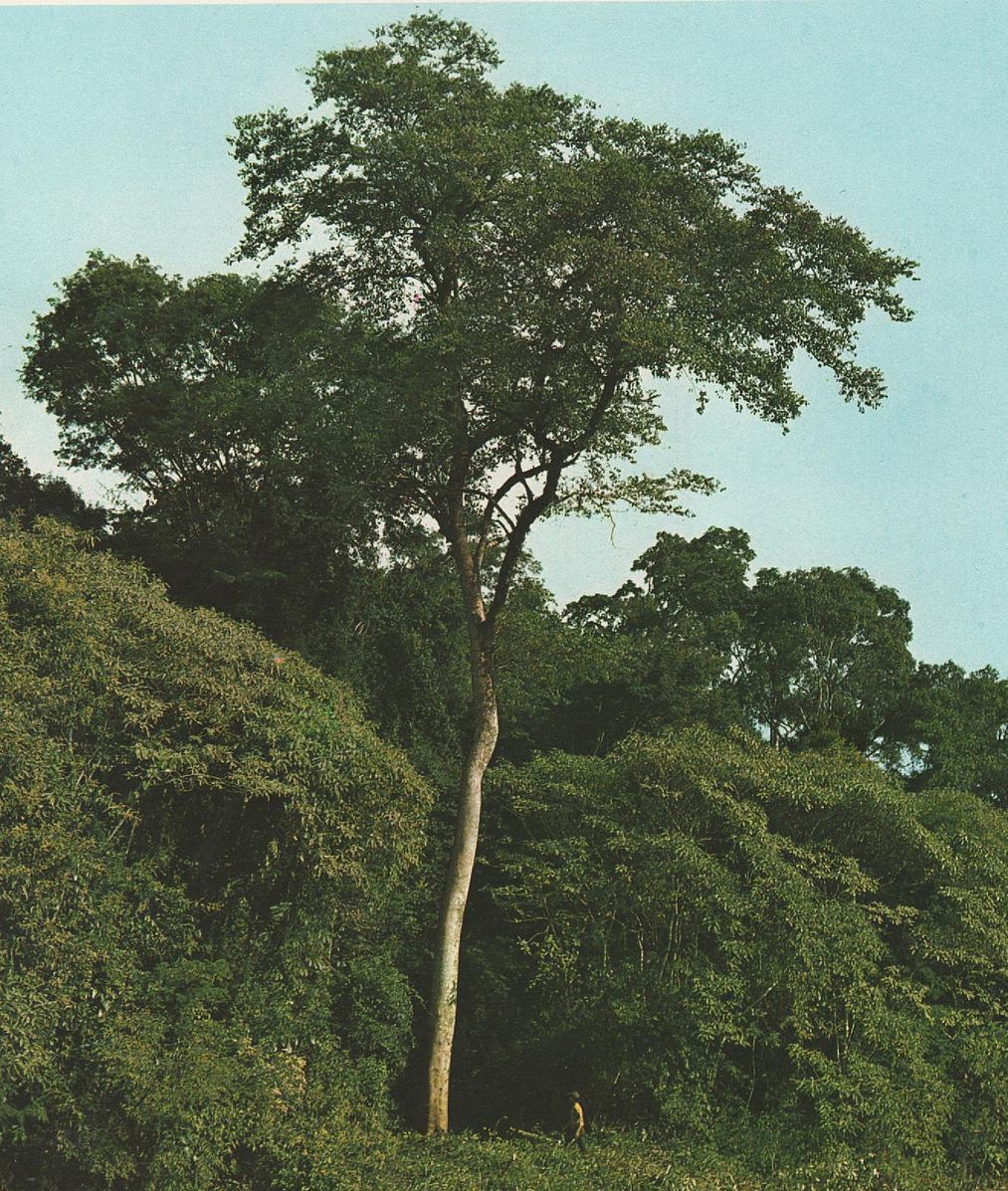

These entanglements between the use of yellow pigments and hues and the history of colonial domination can be traced back as far as 19th century South Asia to the presence of a tall tree in the jungles of Central and South America. Maclura tinctoria or Chlorophora tinctoria is a plant of the mulberry family, native to the neotropical regions of Central and South America, and is commonly known as “dyer’s mulberry.” Its light green fruits are edible, sweet and aromatic, similar in shape to blackberries. Its stalks and bark can be used in medicinal preparations for their anti-inflammatory and healing properties, and its freshly cut wood displays a remarkable yellow tint, which oxidizes with time. As suggested by its common name, Maclura tinctoria is a plant mostly known for its color. Indeed, when processed into chips, its heartwood can be soaked and boiled to make old fustic, a yellow pigment widely used in the textile industry. The General Descriptive Guide to the Museum of Irish Industry, published in 1857, notes that “old fustic was introduced to our dyers about the middle of the 17th century.” Most interestingly, the guide also highlights that “[t]he yellow it imparts is not very bright, and is therefore principally used in obtaining compound colors, forming in junction with Indigo what is called Saxon green; and with other bases various tints of drab and olive.”

The hue described here as “drab” describes what we know most commonly now as khaki—itself a loan word from Urdu, meaning “dust-colored.” The term entered the English language around the 1840s, when Sir Harry Lumudsen—a British military official stationed in Pakistan—introduced dust-colored uniforms to his colonial regiment in order to blend with the dry local landscape during conflict, according to journalist Kassia St. Clair. It was a significant departure from the style of military wear of the time, which traditionally tended to use bright, visible colors as a means to intimidate enemy troops. Bold colors helped military forces look larger than they were in reality, particularly considering the context of battle before the invention of the smokeless gun.

As warfare technology changed, however, khaki uniforms became increasingly popular with the Indian Army during the second half of the 1800s, and by the turn of the century, the color had been adopted by the British Army as a strategic choice. St. Clair remarks that, at the time of the outbreak of the First World War, “increasingly sophisticated use of planes for reconnaissance, coupled with the invention of the smokeless gun, meant that the risks of being visible seriously outweighed the advantages.”

As the conflict came to a close in 1918, St. Clair argues that “khaki had become synonymous with soldiery”—a fact which, as textile historian K.G. Ponting points out, “further increased the use of fustic, an ideal dye for producing this difficult shade.” Indeed, in 1914 the Daily Consular and Trade Reports, published by the US Department of Commerce, highlighted the economic importance of the plant, remarking that whilst WWI had disrupted the supply of important dyestuffs to the United States, “[m]any inquiries have come to British Honduras about the products of the colony that may be utilized in making dye. There are only two of any value, logwood and fustic (Maclura tinctoria), the latter producing the old standard yellow of the English dyer.” Maclura tinctoria, the tall tree with sweet fruits like pale green blackberries; Maclura tinctoria, the raw material of warfare and colonial domination.

It is perhaps in the painful transitions—from saturated yellows to subdued khakis, from rich sweetness to rot—that colonial power makes and remakes itself. Appropriation followed by the depletion of meaning; seizure and occupation followed by absorption and acculturation. Images of violence repeated over and over again; a lie told just enough times to become accepted as truth.

Luiza Prado de O. Martins (she/her) is an artist and researcher whose work examines themes around fertility, reproduction, coloniality, gender, and race. In her doctoral dissertation she approaches the control over fertility and reproduction as a foundational biopolitical gesture for the establishment of the colonial/modern gender system, theorizing the emergence of ‘technoecologies of birth control’ as a framework for observing—and resisting, disrupting, troubling—colonial domination. Her ongoing artistic research project, “A Topography of Excesses,” looks into encounters between human and plant beings within the context of indigenous and folk reproductive medicine, approaching these practices as expressions of radical care. Throughout 2020, she will develop the long-term garden project “In Weaving Shared Soil” in collaboration with The Institute for Endotic Research. She is currently based in Berlin. She is a founding member of Decolonising Design.